Is it time for ‘developing’ China to start funding UN climate aid?

- As a developing country, China does not have to give directly to UN climate funds, such as the loss and damage fund, although it is already a major climate donor

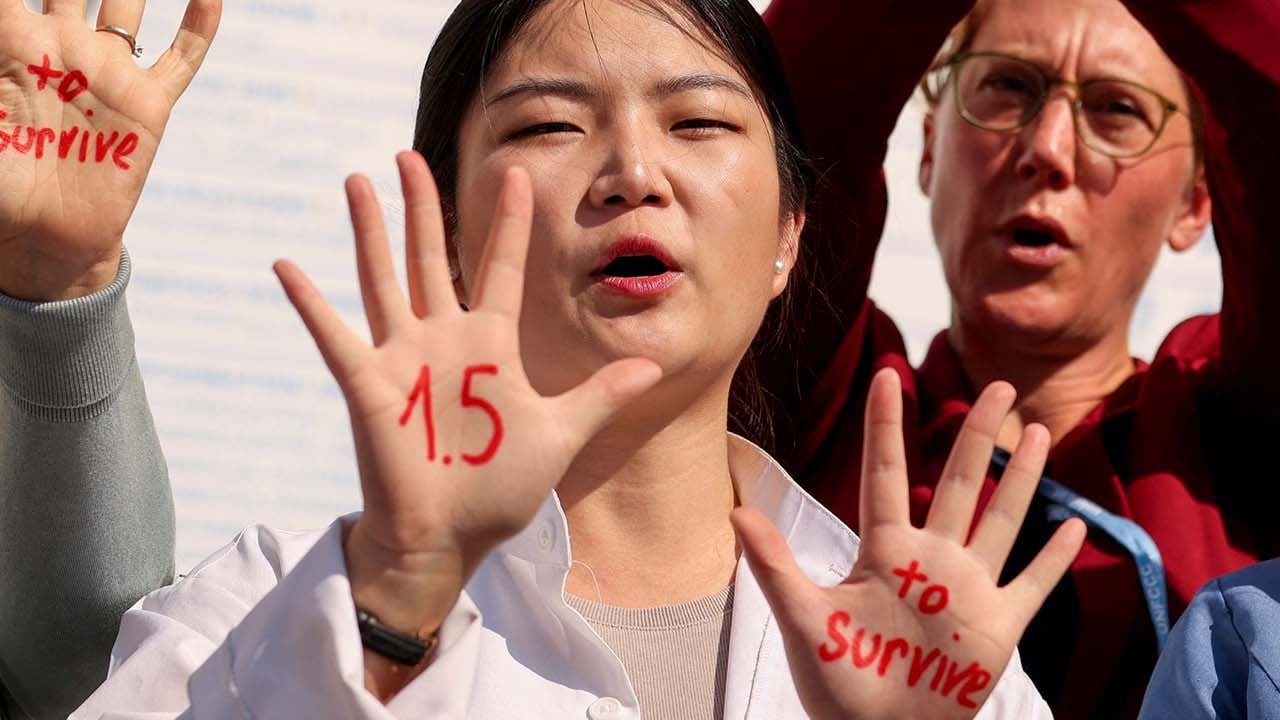

- While the debate over outdated categories rages on, all countries must continue to limit emissions and mitigate climate change

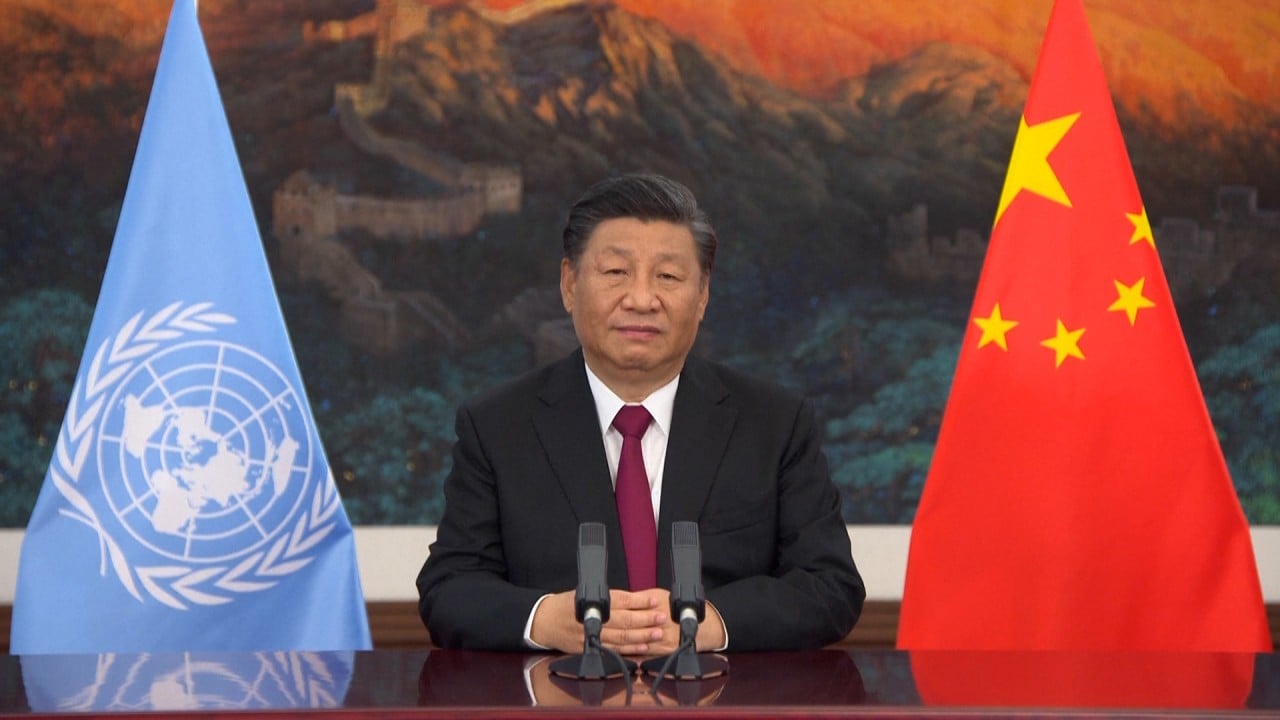

China, accounting for 29 per cent of global emissions, is the world’s largest emitter but will not contribute to the fund. Why not?

Its coal-based economy is the reason for its high emissions and local pollution. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, in 2022 about 56 per cent of all energy still came from coal, despite the major development of renewable energy.

If one is not familiar with China’s status in the UN climate convention (UNFCCC), it’s easy to misunderstand the country’s position. Some clarity on this is central to understanding Chinese attitudes towards its financial contributions.

Under the UNFCCC, China is considered a developing country, not an Annex 1 country. Annex 1 countries include the industrialised countries that were members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1992 when the UNFCCC was adopted, plus countries with transitional economies (EIT parties), including Russia, the Baltic states and several central and eastern European states.

According to the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), China is still classified as a developing country. It is on the list of upper middle-income countries (those with a per capita gross national income of US$4,096-US$12,695 in 2020). Therefore, China does not contribute directly to the Green Climate Fund, or the new loss and damage fund. Contributions here are based on the principles and provisions of the UNFCCC. China is not obliged to provide climate financing in the same way that Annex 1 countries are.

Nevertheless, a shift has occurred. For years, China was a recipient of climate financing, but it has increasingly become a donor country.

The country’s role as an aid provider has strengthened in recent years, as it has gained experience. China adheres to the principles of the UNFCCC, but to show solidarity with developing countries that have not progressed as far as itself, it finds other ways to help.

No deadline was set for the goals of the South-South Climate Cooperation Fund, but China’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua said at COP27 that 2 billion yuan (US$310 million) had been given to developing countries to address climate change.

China steps up climate fight with belt and road green finance partnership

But some sources express uncertainty about how much the fund has contributed so far. Reasons mentioned include coordination challenges among Chinese actors and the coronavirus pandemic, which has resulted in slower implementation.

A recent post in Carbon Brief concluded that China contributes significant sums of money to developing countries, and in direct climate financing to developing countries it can even compete with the largest donors from developed countries.

As the world’s second-largest economy and the largest carbon emitter, China faces growing expectations to increase climate financing to support developing countries. Many argue that the categories under the climate convention are outdated and that major emitting countries like China and India should contribute to the UN funds.

China has no formal obligation to participate but emphasises solidarity with, and often speaks on behalf of, developing countries.

China’s financial contributions outside the climate convention could perhaps be seen as a form of pragmatism, expressed in climate support to developing countries. Countries believe it is not possible to deliver what is needed on climate if we continue to stick to decades-old categories. But changing the categories is likely to be very difficult.

Debates on structural changes and fairness must be held while all countries continue to work to both limit emissions and adapt to the consequences of the climate changes we are experiencing.

Dr Gørild M. Heggelund is a research professor at Fridtjof Nansen Institute (Norway) and a Chinese policy expert

Iselin Stensdal is a researcher at Fridtjof Nansen Institute (Norway). She has researched China for over a decade, focusing on Chinese climate governance

Both were observers at Cop28