Why Indonesia shouldn’t rush to join the OECD ‘rich man’s club’

- Plans for an accelerated accession come as global concerns grow over the organisation’s transparency and fairness towards developing nations, particularly in its tax policies

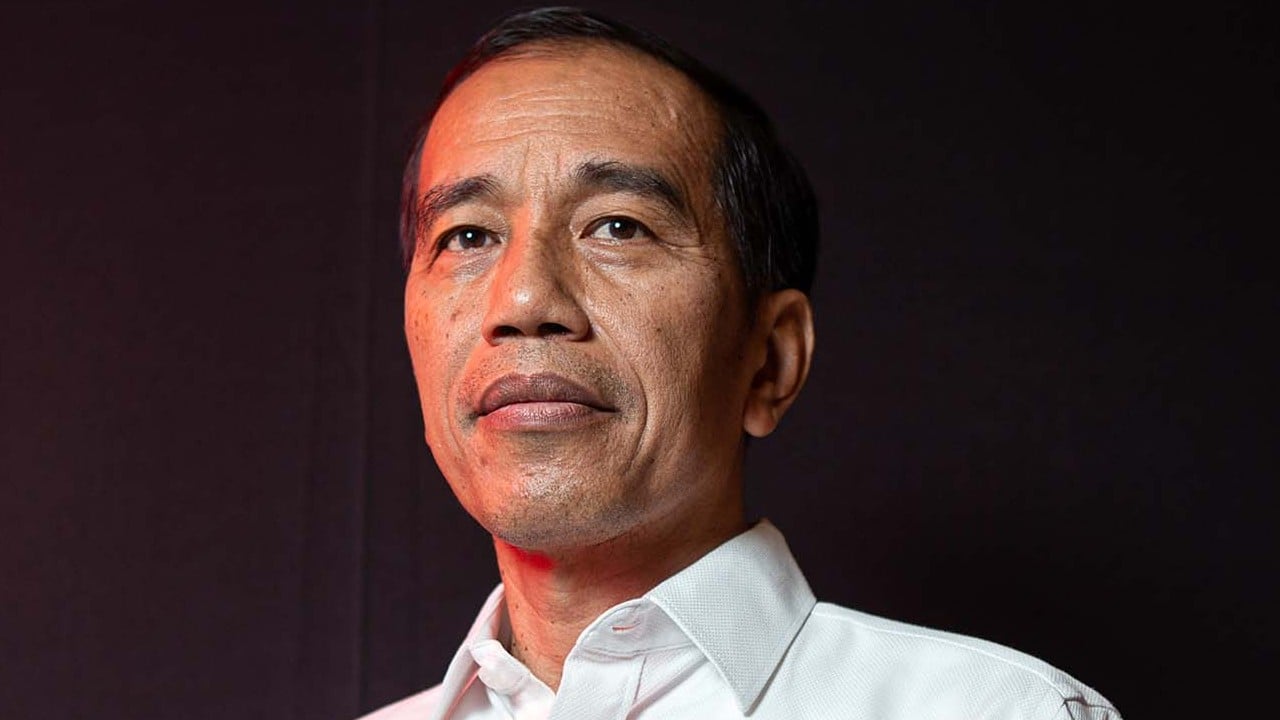

Indonesia seems desperate to join the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), regarded as a rich man’s club. President Joko Widodo is pushing for an accelerated process and announced in October that it would set up a national committee to do so.

Indonesia has been a key partner of the OECD since 2007 and is familiar with its workings. Still, its target of completing accession within four years is ambitious, when the process can take five to eight years. The last two members to join the OECD – Costa Rica in 2021 and Colombia in 2018 – took about five years each.

Besides Indonesia, six other countries are in accession discussions with the OECD, namely Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Peru and Romania. The OECD’s key partners include China, India and South Africa.

To join the OECD, major reforms are needed to align a country’s laws, policies and practices with OECD standards, particularly in the major areas of trade, finance and taxes.

Indonesia’s policy alignment has been going on for years, through a series of joint work programmes, the current, fourth, iteration of which covers 2022-2025. This latest work programme includes “priority areas” such as the sensitive arenas of tax policy and administration, as well as investment, education and skills, labour market policies, green growth and corporate governance.

The deal was hammered out under the OECD’s “inclusive framework”, which covers more than 140 countries and jurisdictions. But amid unhappiness, countries including Kenya, Nigeria, Sri Lanka and Pakistan did not join the agreement.

“The deal is bad for everyone, but worse for developing countries,” said Eurodad’s Tove Ryding. “The OECD-led negotiations have been highly secretive, and were never anywhere near global.” Oxfam said the tax deal “was meant to end tax havens for good. Instead it was written by them”, labelling it a “mockery of fairness”.

In July, the Financial Times exposed how the OECD pressured the Australian government to weaken important transparency requirements in the country’s taxation of multinational companies, for fear they “undermined its own efforts to make multinationals’ affairs less opaque”.

“We grew especially worried in 2021 after the OECD released their anaemic proposals, which are expected to provide minuscule sums to developing countries and emerging markets in return for holding off imposing digital and other taxes on multinationals,” they wrote.

Indonesia’s membership in international organisations is regulated by presidential decree, which states that considerations must include national priorities and a cost-benefit analysis, among others. There is no mention, however, of the need to examine the world’s geopolitical situation and international relations.

But attention should be paid to the fact that there are organisations formed by or affiliated with big competing countries, such as the United States, Russia and China.

Joko Widodo’s steady, pragmatic diplomacy shows Asean a way forward

Indonesia becoming an OECD member will take up more of its energy, time, thought and money. The OECD has 450 standards to meet, hosts some 4,000 meetings a year, and produces more than 500 major reports and country surveys. Considering the weak coordination between Indonesia’s ministries and institutions, it is not inconceivable that OECD advisers would have to be stationed in the country.

Many roads lead to Rome. China, a country with a lot of potential, in common with Indonesia, became a leading developed nation not because of the OECD, but because it upholds the principle of self-reliance. For Indonesia, OECD membership does not need to be a priority – and can even add to its burdens.

Dian Wirengjurit is a former Indonesian ambassador to Iran and Turkmenistan (2012-2016). The views in this article are solely his own