China’s Belt and Road Initiative rightly offers charity-free development

- Free of the ‘white man’s burden’ to provide charity to poor countries, China’s infrastructure-focused model treats poor countries and their people as customers and business partners – a more respectful way of dealing with them

In Paul Theroux’s 2002 book Dark Star Safari, he travels from Cairo to Cape Town on low-cost transport, staying in cheap hotels. It was his return to Africa after 35 years. As a young man, he had taught in Malawi and lectured at a university in Uganda. Malawi had been one of the world’s poorest countries. On his return, he wanted to see how it compared.

Theroux was appalled to find that things were mostly not better, and in many cases worse. He visited small cities such as Mbeya in western Tanzania and Mzuzu in Malawi. “Mbeya,” he wrote, “as a habitable ruin, attracted foreign charities. This I found depressing rather than hopeful, for they had been at it for decades and the situation was more pathetic than ever.”

In Mzuzu, he looked for a vehicle to hitch a ride. “There were many vehicles in Mzuzu,” he said, “the most expensive of them of course were the white four-wheel drives displaying the doorside logos of charities.”

A four-wheel drive was important because the roads were so bad. The drivers of these vehicles did not give him a ride. But his annoyance was not because of that, but because “the vehicles were often driven by Africans, the white people riding as passengers in what resembled ministerial seats”.

The charitable urge that brings well-funded charities to poor countries is a modern version of the antiquated, self-consciously well-intentioned “white man’s burden” mentality. It’s our burden, the charity’s donors and employees believe, to help these people – they require charity. But the charity often goes awry, providing more good jobs for charity workers than help for its receivers.

China’s approach in helping these countries is different. More of a business model, it is an investment with an expectation of a return if all goes well. In a typical investment deal, when all goes well, the investment’s recipients also gain benefits.

This model treats poor countries and people in them as customers and business partners, not recipients of charity – a more respectful way of dealing with them, and free of the stigma of the white man’s burden.

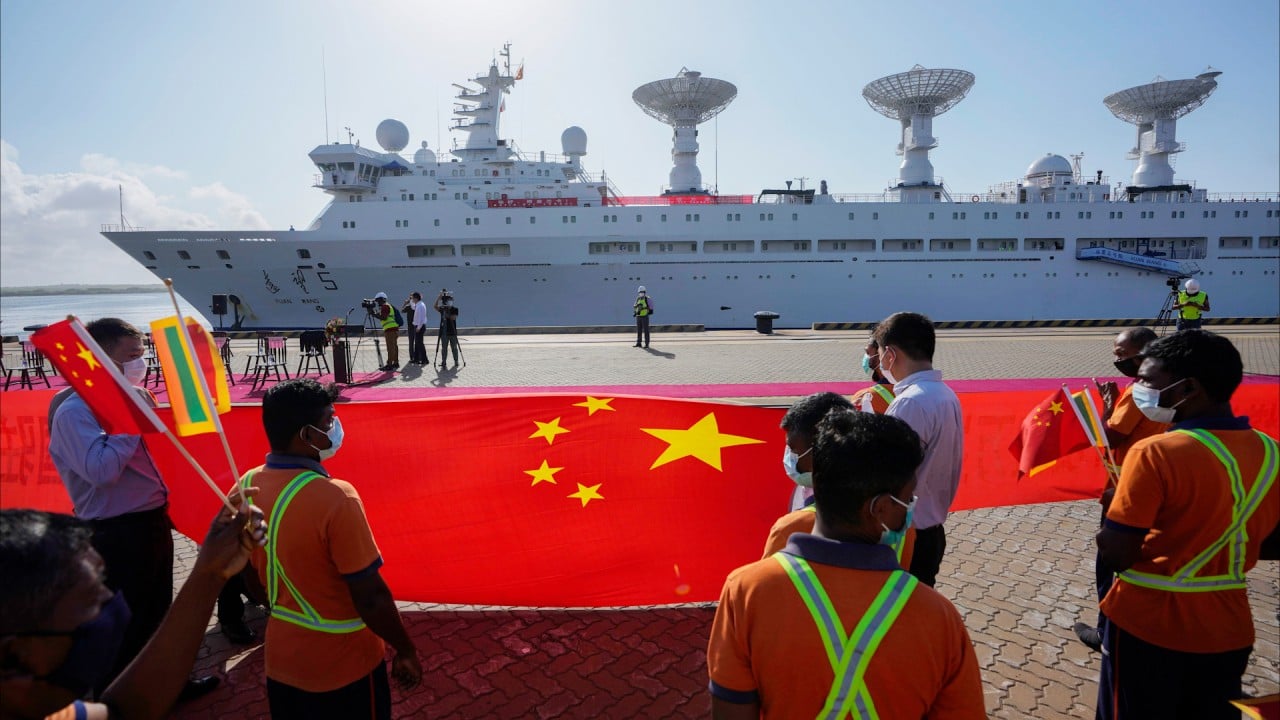

China’s investments benefit many poorer countries around the world. These are investments in whole countries and commerce between countries, focusing especially, as the white paper released in October by China’s State Council Information Office, “The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future”, says, on the “growing connectivity of infrastructure”.

In Africa, examples are the Mombasa-Nairobi and Addis Ababa-Djibouti railways. In many countries in Africa, the roads are very bad, as Theroux observed. Improving the ease of transport and communication can bring these countries fully into the modern world of commerce, a key to increasing prosperity.

While subject to the same allegations of corruption and overly optimistic projections as many infrastructure projects in developing countries, the debt-financed structure imposes more discipline than does charity.

It is a challenge for China to build infrastructure using local workers. Hence, infrastructure investments must include investments in education, especially vocational education.

Many Belt and Road Intiative projects are under way worldwide to improve infrastructure connectivity. Not all projects will be successful, of course, or profitable. But the application of effort and drive is likely to bring success to the endeavour overall, whether through the eventual spectacular success of only one or two projects, or a general lifting up of many countries.

We are at last starting to see the countries that were first called “underdeveloped”, then “less developed”, then “developing”, finally actually developing rapidly.

Michael Edesess is an adjunct professor in the Division of Environment and Sustainability at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology