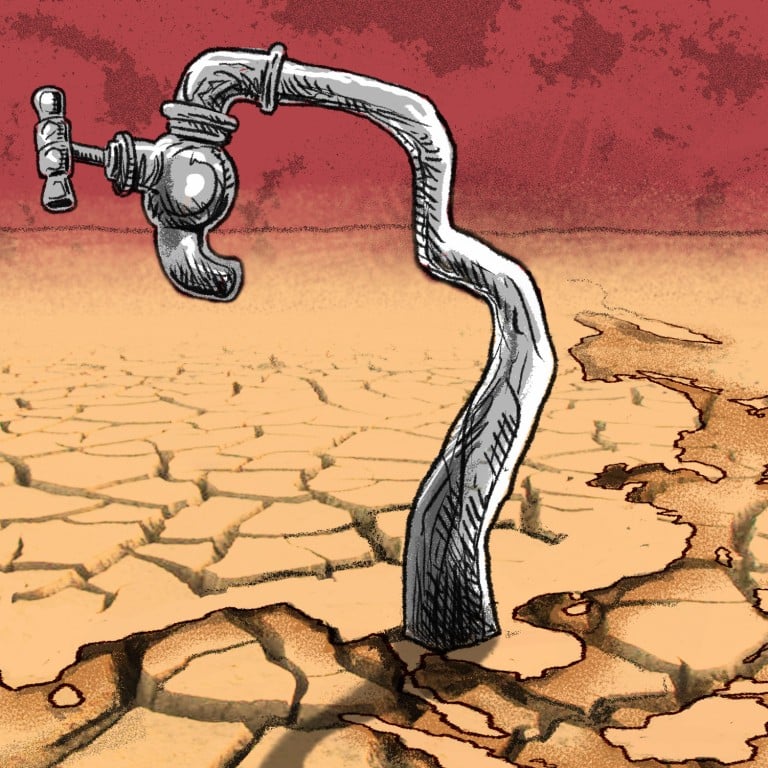

Climate change: water scarcity is fuelling new crises across Asia

- Attendees at COP27 failed to prioritise the urgent climate adaptation and mitigation policies needed to promote water security worldwide

- Water scarcity must be high on the agenda at this year’s meeting or the crisis risks becoming irreversible and driving new levels of conflict and suffering

With COP28 on the horizon, the interlinked challenges of climate change and global water scarcity must be made a priority before the crisis becomes irreversible. The future habitability of the planet hangs in the balance.

China’s water crisis is a complex issue that demands urgent action across all sectors. Current policies are inadequate for the scale of the problem. Comprehensive transformational strategies and investments in sustainable water infrastructure are needed to avert catastrophic effects in the country.

Thailand has suffered severe drought, with global supplies of sugar and rice taking a hit. This has led to reliance on water tankers and trucks in rural communities.

Climate effects, land use changes and uncoordinated development are conspiring to create a severe water crisis across Southeast Asia. Urgent cooperation is needed to improve water governance, curb pollution, protect watersheds and build climate resilience. Regional countries need to work together to confront the existential threat posed by water scarcity and prevent catastrophic effects on agriculture, economies and human welfare as regional stability also depends on protecting water.

Reduced snow cover and rising temperatures are causing Himalayan glaciers to lose tons of ice each year. The Hindu Kush Himalayas could lose up to 75 per cent of their volume by century’s end because of global warming, causing both dangerous flooding and water shortages for the 240 million people living in the mountainous region. Meanwhile, excessive groundwater pumping is also draining the South Asian aquifers on which up to 80 per cent of India’s population relies.

The climate change-exacerbated global water crisis is no longer a distant threat but a present reality demanding immediate action. Acute water stress in major Asian economies jeopardises the water security of billions of people. Climate effects such as droughts and floods have already diminished agricultural yields, disrupted electricity generation and strained drinking water access for millions of people living in these regions.

‘Difficult to agree’: China-India border row spills over into water resources

This includes investments in watershed protection, desalination, irrigation efficiency, transboundary cooperation and sustainable technologies for water conservation, treatment and reuse. Failure to act decisively will have massive humanitarian, political and economic consequences.

As the latest UN climate change conference nears, it is time for the world to confront the interlinked challenges of climate change and water scarcity before it is too late and, as some pundits expect, World War III breaks out over water.

Professor Syed Munir Khasru is chairman of the international think tank IPAG Asia-Pacific, Australia, with a presence also in Dhaka, Delhi, Dubai and Vienna