The stated goal of these agreements, as exemplified by the US-Japan deal, is to fortify and diversify supply chains for critical minerals, thereby advancing the widespread adoption of EV battery technologies. However, beneath the surface lies a deeper strategic motive – to reduce the global competitiveness of Chinese-manufactured EVs while concurrently lessening dependence on

China’s mineral resources.

The US call for diversification and risk mitigation within supply chains serves not only to enhance the security and sustainability of its EV industry but also to exert influence over the competitive landscape of Chinese EV manufacturers. It is, in essence, a calculated effort to assert control over the realm of these critical minerals.

The measures being taken by the US and its allies are, however, unlikely to seriously affect China’s critical mineral exports. Chinese-produced EVs still retain a cost advantage, for one. Moreover, Chinese battery and EV manufacturers are intensifying their efforts to establish a foothold

in overseas markets, potentially exploring untapped opportunities in emerging economies.

The reason lies in the constrained supply of these essential minerals. Despite their rhetoric and protectionist measures, Western countries are likely to exercise caution because of China’s prominent status as a major global supplier of

critical minerals.

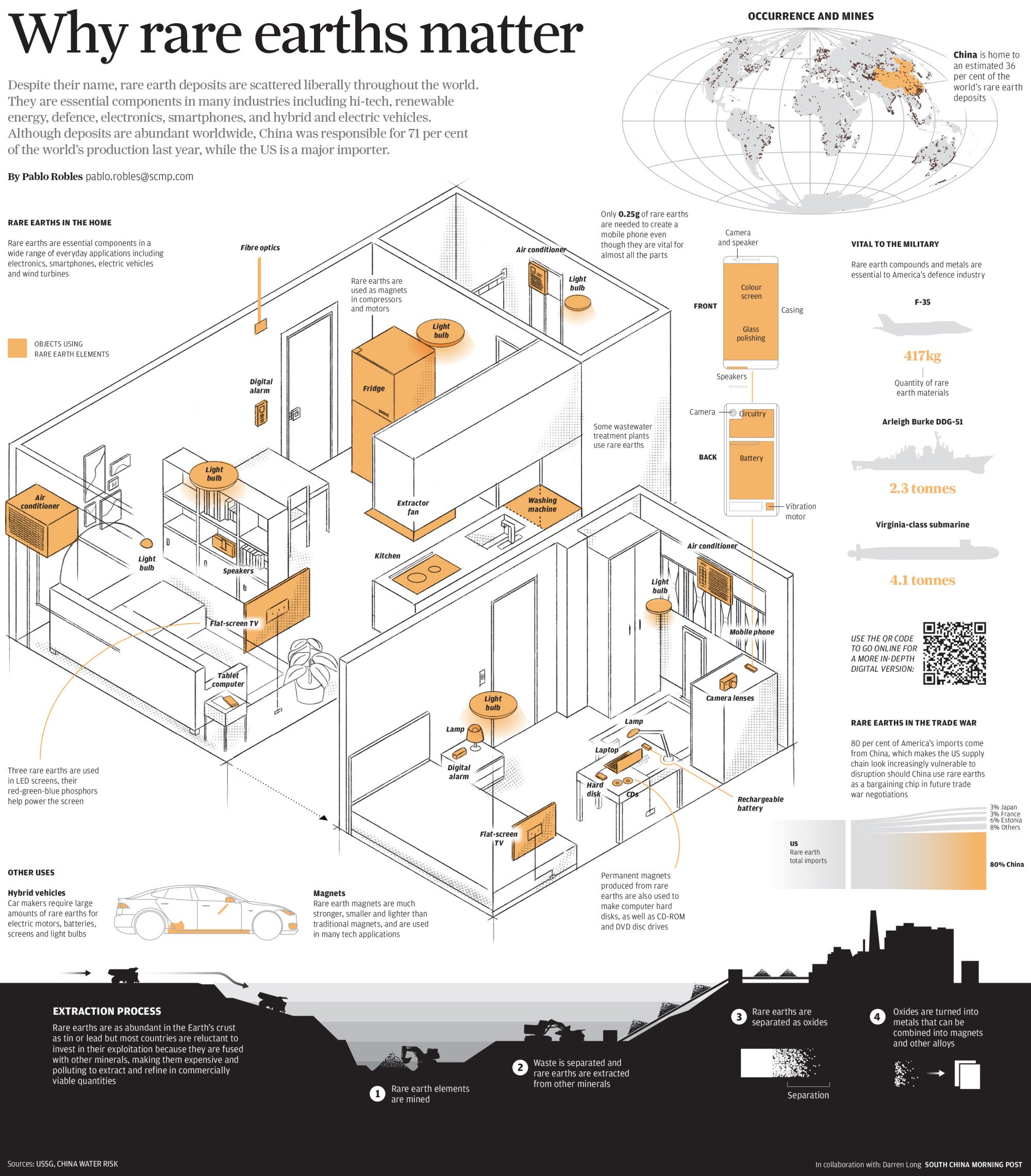

A substantial portion of the minerals indispensable for the global

green energy transition originates in China – it provides about 90 per cent of the world’s gallium and 70 per cent of rare earth minerals. In a bid to expedite the revitalisation of its rare earth magnet supply chain and curtail its reliance on China as the primary source of rare earths, the US Congress has unveiled the Rare Earth Magnet Manufacturing Production Tax Credit Act.

This legislation has been crafted to encourage domestic production of rare earths and advance the broader initiative of

industrial decoupling from China. The bill creates a US$20 per kg production tax credit for magnets manufactured in the US, or US$30 per kg for magnets manufactured there and for which all component rare earth material is produced, recycled or reclaimed within the US.

Despite this, Washington faces formidable challenges in constructing its own comprehensive rare earth magnet supply chain, with high infrastructure development costs and lower ore grades among the most prominent hurdles.

Meanwhile, China remains

a dominant force in rare earth reserves, with some 34 per cent of total global reserves, estimated at 44 million tonnes. In contrast, the US can only lay claim to an estimated 2.3 million tonnes of rare earth reserves. This disparity, coupled with poor returns on previous investments in rare earth mining, renders the prospect of achieving profitable production levels particularly daunting for the US.

Furthermore, China currently commands more than 80 per cent of the global capacity for

rare earth processing. It also imports rare earth metal ores for smelting and separation before exporting the product. This ability to import and re-export rare earth metal ores is a key difference rooted in China’s status as the global leader in rare earth refining technology.

To offset this handicap, the US has been working hard to establish strategic supply chain partnerships with both Australia and the European Union, aimed at advancing rare earth separation technology. Even so, EU and Australian refining capabilities trail China’s cutting-edge technology.

The absence of a comprehensive industry chain – encompassing mining, separation and refining – presents challenges in achieving large-scale rare earth purification. As a case in point, Australia’s rare earth separation facilities can only satisfy 30 per cent of Japan’s demand, leaving Tokyo heavily reliant on China to fulfil the remainder of its needs.

The EU is intensifying its focus on “urban mining”, which involves the extraction of minerals from discarded batteries, mobile phones and similar sources. At the same time, it is also striving to expand its mining activities on home soil and pursuing partnerships with mineral-rich nations in the Global South.

The US is engaged in similar endeavours, funnelling substantial investment into the production of new batteries and diversification of mineral sourcing. It has also reactivated the

Mountain Pass rare earths mine in California, the largest in the country, and is exploring opportunities for new mining ventures across the nation.

The US and its allies find themselves in an intense race against China for control over rare minerals, a contest that carries the potential to take an uglier turn in the future.

Dr Imran Khalid is a freelance contributor based in Karachi, Pakistan