The rise of Asia’s virtual influencers: are we being manipulated?

- Virtual influencers are good news for brands: they don’t complain and they won’t lose followers due to scandals

- But they are incapable of forming authentic consumer opinions so it’s unclear how they benefit consumers and the wider public – regulation is long overdue

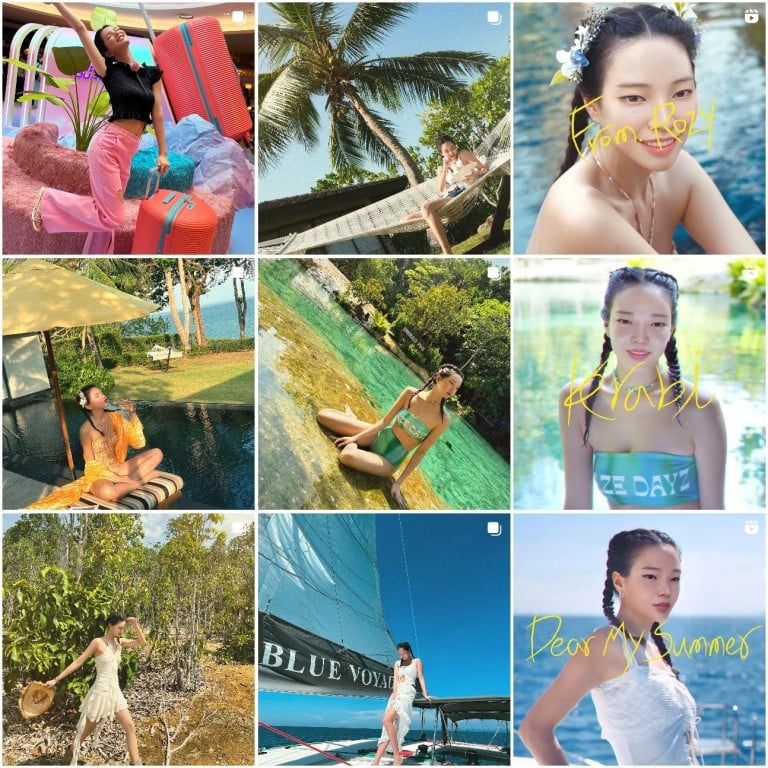

She stands rather tall at 5ft 7in (170cm), with ever so lightly freckled skin and not a hair out of place. Her motto is the somewhat bohemian-sounding hakuna matata, a Swahili phrase meaning “no worries” that was immortalised in the wildly popular Disney animation The Lion King.

She’s from Seoul, South Korea. Her name in Korean means “one and only” and indeed, her emergence has marked a new era in influencer marketing in Asia. The sporty type, she loves surfing, skateboarding and running. Her birthday comes around every August 19, and yet she is forever 22.

In one post, she is resting her chin on her fist, in front of a dreamy archway covered entirely in pink blossoms and near a suitcase. She is looking every bit the glamorous jet-setter – or high-profile ambassador for a prominent luggage brand. The fact that she’s not a real person hasn’t affected her earning power. Appearing in advertisements for major brands, she is estimated to have pulled in over 2.5 billion won (US$1.8 million) last year.

In the three months after her debut in 2020, about 150 other computer-generated humans emerged on South Korea’s social media and advertising platforms. This may be a sign of things to come in Asia.

However, these drama-free, low-maintenance brand avatars are not exactly problem-free. To put it another way, your very cool, perfect non-human influencer might come across as too perfect, and therefore not authentic.

Obviously, unlike human key opinion leaders, virtual influencers can’t try the product they are promoting or tell you about an experience they have gone through themselves.

It’s strange when you think about how social media influencers emerged – people wanted authentic consumer opinions by someone they could trust. And yet, in the world of marketing today, it has become not just acceptable, but even desirable, for a figment of an animation studio’s imagination to be presenting some version of authenticity to consumers.

We are clearly being manipulated by the brands that are using virtual influencers, by the companies that want us to think and behave in a certain way that props up their bottom line. This kind of advertising primarily benefits brands; whether it offers actual advantages for consumers and the wider public is questionable.

With virtual influencers holding sway over a youthful Asian market that is immersed in technological fantasy and alternative reality, even ad agencies are increasingly concerned about the ethics of using tech-powered influencer content. One primary concern is: how is this any different from using a wholly fictitious narrative to peddle your goods?

And then there is a danger that few ad agencies seem to have considered so far: a virtual influencer’s sudden crash in popularity. For example, take Ayayi, a virtual influencer from China. In 2021, her debut image quickly went viral on a Chinese social media platform. Ayayi’s rise in popularity was attributed to her good looks and the growing interest in the metaverse between 2021 and 2022.

Rise and fall of unlikely influencer highlights plight of older Chinese

However, it soon began to fade, and her posts dwindled with the lack of interest in her. Today, her Instagram account has only 12,300 followers, a mere drop in the social media ocean. While a human influencer can lose followers too, it will usually be due to a scandal, instead of bored disinterest.

Still, the stakes for influencer marketing in general, and virtual influencer marketing in particular, are skyrocketing. According to an industry report, the global market for influencer marketing is estimated at a record US$21.1 billion in 2023. In the Asia-Pacific region, younger consumers from China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and other markets are driving the trend.

In China, where e-commerce platforms dominate, the virtual idol industry was estimated to be worth US$540 million in 2020, with a 70 per cent year-on-year growth rate. That’s because the trend is being driven by a 390 million-strong audience of Gen Z and millennials.

Given the number of young impressionable post-millennials among this audience, it is clear that a framework for regulating virtual influencer marketing is long overdue: disinformation, deepfakes and outright deception must be prevented from gaining traction.

There is no denying that the virtual influencer has emerged as a cutting-edge marketing tool but instead of giving it a free pass, we need to be careful that it doesn’t morph into our worst AI nightmare.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a freelance journalist based in Madurai, southern India