The US should counter China’s dominance in the Global South with trade, not more arms

- The US still has distinct advantages, including, critically, a growing population. But it must ease off sanctions and its single-minded focus on security

- Instead, it must present the developing world with more broad-based economic cooperation and a return to globalisation

Brics, the bloc compromising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, has long been accused of geopolitical incoherence and irrelevance. The five countries differ among themselves on several global questions and have varied equations with the West, ranging from friend to foe.

If there is one country still in a position to compete with China’s influence in the developing world, it’s the United States. America still enjoys distinct advantages over China.

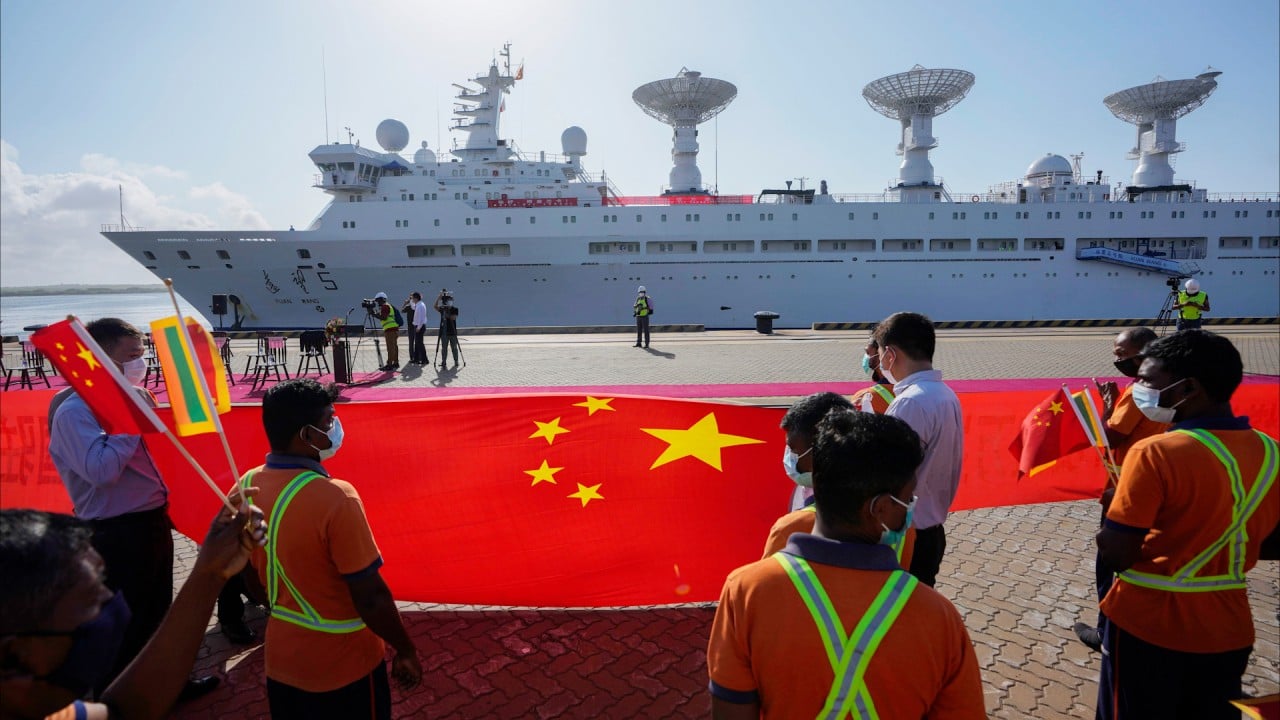

So far, America has not leveraged these advantages sufficiently. China’s burgeoning influence in the developing world increasingly stems from it being the only major power able or willing to present economic cooperation. And Beijing’s refusal to indulge in value judgments on political and social issues make it an attractive partner to many.

So Beijing’s economic influence in Asia remains largely uncontested.

Washington has instead focused on Taiwan and bolstering security ties with allies such as India, Japan and the Philippines. But that has only made many countries in the region more anxious as they try to balance ties between China and the US.

The ubiquity of sanctions in US policy has also been divided the developing world. According to the US Treasury Department, by 2021, Washington had imposed more than 9,000 sanctions. That year, Biden added 765 more. US-sanctioned countries make up over one-fifth of global GDP.

How sanctions on Russia risk mass destruction of the global economy

There are legitimate reasons the US has prioritised military goals over economic ones. Domestic politics is a key factor. In the wake of sustained trade protectionism and rising anti-immigration sentiment, Washington has found itself unable to champion a more open and globalist economic vision for the world.

But that has meant a single-minded focus on security matters, which has made the defence industry the key driving force behind US engagement with the world. In its last fiscal, US arms exports surged by a 49 per cent.

For many countries in the developing world, that feels like a mismatch in priorities. To compete with China, America should instead present them with opportunities for more broad-based economic cooperation and a return to globalisation.

Mohamed Zeeshan is a foreign affairs columnist and the author of Flying Blind: India’s Quest for Global Leadership