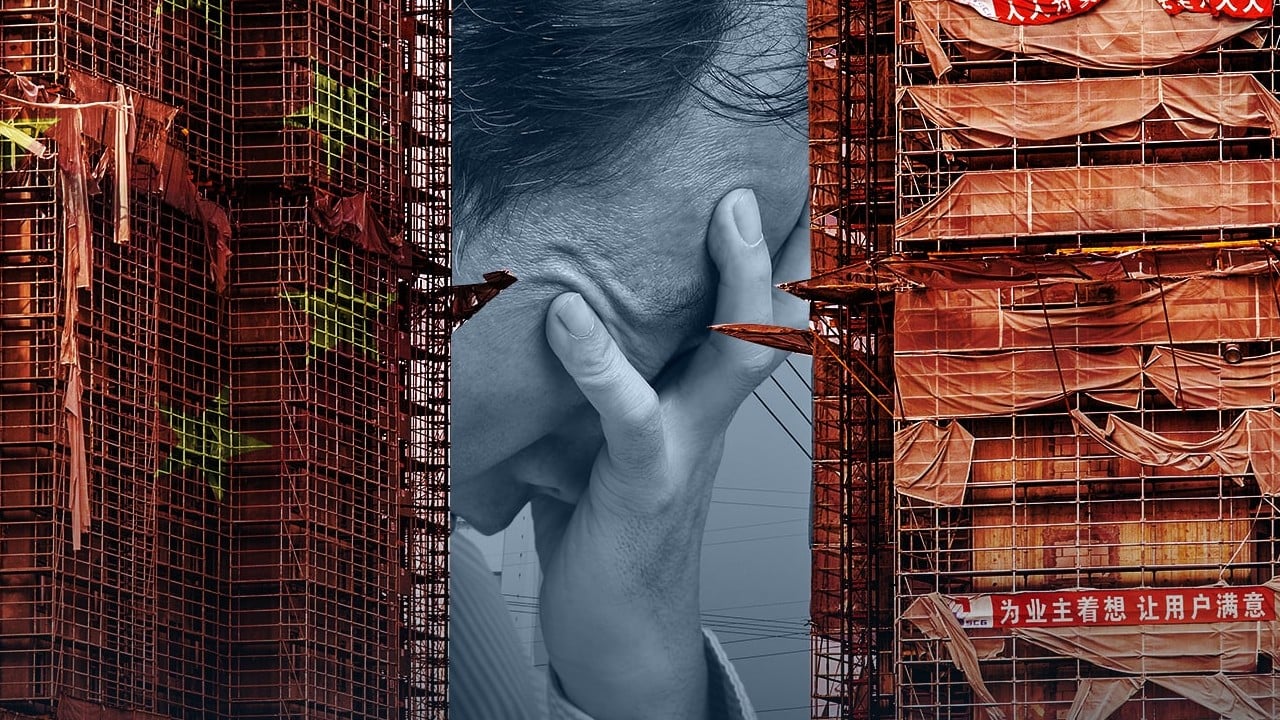

To avoid an economic meltdown, China must not repeat America’s mistakes of 2008

- Any rescue plan for a crashing property sector must be fair by supporting prudent homeowners and penalising errant banks and companies

- Bailing out the big banks while leaving ordinary citizens to suffer the pain of foreclosure, as the US did, will only fuel populist anger

Economic downturns have commonalities across history and locations, as Harvard professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff taught us in This Time is Different. The book showed that banking and economic crises are often associated with falling equity markets and house price declines.

Once house prices begin to fall, economic woes deepen. When home prices are rising, owners feel much richer, and so they spend more as the good times roll.

But when the business cycle turns, and if home prices fall, consumers see their net worth shrink dramatically. In response, homeowners stop spending – a sensible and logical thing to do. But when many consumers all do the same, the economy falters, and a downward spiral can commence.

Such large declines would be bad news for the expectations of homeowners and consumers. A negative feedback loop of house price falls, consumer pullbacks and economic effects could begin, and may already be visible.

A key lesson comes from 1930s America: the Great Depression taught that mortgage defaults, foreclosures, the destruction of household wealth and the subsequent evisceration of consumer confidence and spending are challenges that must be addressed.

When the economic depression hit, US house values slumped as jobs vanished. Banks reacted by refusing to extend mortgages, worried about repayment. This risked throwing many into homelessness and penury, worsening the economy and prospects. Then president Franklin D. Roosevelt responded by creating a government programme replacing short-term, interest-only loans with loans that would be paid off fully over 15 years.

The largest banks would survive severe recession, Fed ‘stress tests’ show

By doing this, Roosevelt created breathing room for a million homeowners in distress, at a cost of US$3.5 billion. The president put a floor under the shaky housing market at a key juncture. In addition to providing a lifeline to homeowners, the programme forced banks to take haircuts on the loans that were being repaid, making them bear some responsibility.

Three points are important for China’s policymakers from this historic case.

First, a mortgage support and relief programme should not be designed to help those who cannot make a bridge from current economic stress to future stability. It should be designed to extend time frames, thereby creating room for those who can pay. Providing time for the economy and consumers’ finances to recover is the goal.

Second, the original lenders, in China’s case the banks backing the real estate developers, must publicly bear some of the economic pain. They made the loans, and they should face consequences for mistakes and poor business practices.

Third, fairness is important. Policymakers must spread the cost to those responsible for causing it. If such fairness is not seen, they risk setting the stage for anger among those who do not benefit, against banks and directed at CEOs and real estate tycoons. That anger is politically and socially corrosive and potentially destabilising.

The 3 burdens for China’s middle-class

America’s more recent history, during the US-caused 2008-2009 global financial crisis, provides lessons of what not to do, because some of Roosevelt’s lessons were sadly forgotten. In the response to the great financial crisis, US policymakers added US$787 billion of stimulus. The Federal Reserve cut rates to zero. But unemployment leapt from 5 per cent to 10 per cent from 2007-2009.

Crucially, American policymakers did not help mortgage holders. As a result, foreclosures dramatically increased, leaping by 120 per cent from 2007 to 2009, to 2.8 million. That mortgage pain extended the length and depth of the recession.

In addition, US leaders did not make senior business leaders pay for their mistakes. No bankers went to jail. Banks like Goldman Sachs were paid 100 cents on the dollar for their bets in complex securities, saving billions. In AIG, the firm whose foolish bets helped to trigger the crisis, business executives were paid bonuses even after destroying their company and costing taxpayers a US$170 billion bailout.

Populism can grow from such mistakes – from the seeds of economic anger, unfairness and a sense of being left behind. We can see that in America and elsewhere today.

Chinese leaders need to make sure prudent homeowners are helped, and risk-taking leaders and firms pay a very visible price. Doing so may help insure against public anger, while spurring economic growth.

Unlike the US, where government officials’ coziness with Wall Street meant homeowners suffered while bankers did not, I expect China’s leaders to be willing to mete out economic pain and, when necessary, legal consequences, on firms and CEOs who bear some responsibility.

Economic downturns are rooted in housing price declines. China can look to lessons from the past, stabilise house prices, provide breathing room for consumers, and punish errant firms and leaders, if the country is to speed its recovery and avoid a long-term slump.

Stuart P.M. Mackintosh is executive director of the Group of Thirty