How Thailand can draw closer to China despite US rivalry and geopolitical tensions

- The Thai military should focus on regional peacekeeping with China, especially in Myanmar, while Thailand must remain a safe haven for investment

- Bangkok should also promote people-to-people connections, including in tourism, and keep the local media free from foreign interference

July 1 marked the 48th anniversary of the formalisation of Sino-Thai relations. Today, China is Thailand’s largest trading partner with US$135 billion of trade last year, about 18 per cent of Thailand’s total.

Thai exports to China have also jumped, from just US$1.82 billion in 1995 to US$37.7 billion in 2021, a testament to China’s burgeoning middle class and Thailand’s growing competitiveness as a manufacturing and agricultural powerhouse.

While receiving a Chinese delegation earlier this year, Pheu Thai Party leader Chonlanan Srikaew pledged to “drive more trade agreements, promote investment, mutual import-export, tourism as well as the exchange of technology”.

Yet for Sino-Thai ties to meaningfully deepen, broaden and weather the coming decades, Beijing and Bangkok must address the elephant in the room: incipient geopolitical tensions largely stemming from the Sino-US rivalry.

Yet, as Washington increasingly applies pressure on Southeast Asian nations to pick sides in what it construes as a shoring-up of its regional influence against potential challenges from China, Thailand may be forced to choose.

Second, Thailand should position itself as a safe haven for investment amid the increasing Balkanisation of the global financial and supply chains. The war in Ukraine has kick-started a cascade of reorientations by multinational corporations and assets, with many moving from China to Southeast Asia in search of greater policy certainty.

Small and medium-sized enterprises in Northeast Asia concerned by the potential fallout from military tensions in the Taiwan Strait have been eyeing Thailand as a cheaper, more regionally connected production base. Such divestment incentives also apply to Chinese companies looking for fertile ground for growth, both domestically and abroad.

Thailand is no stranger to Chinese state-owned enterprises, such as SAIC Motor, which has teamed up with Charoean Pokphand Group to leverage Thailand as a hub of product internationalisation.

While Thai businesses have largely profited from the astronomical rise in China’s purchasing power and Chinese markets over the past few decades, some argue that such dividends have not trickled down to the lower-middle and working classes.

Tensions between the Thai population and Chinese visitors could well arise due to many factors, including economically rooted resentment, but also stereotypes, religious disagreements or an increasingly politicised media space where portrayals of China’s rise are often swayed by vested interests.

Chinese tourists in Thailand face jail for stepping on coral, touching starfish

The Thai government must strive to ensure its media outlets remain free from foreign interference and that coverage of its relationships with the US and China alike remains balanced, candid and fact-oriented. Beijing, on the other hand, must think prudently and critically about how China can gain even more trust, and win Thai hearts and minds.

A win-win partnership awaits both China and Thailand, but key hurdles must first be overcome.

Brian Wong is an assistant professor in philosophy at the University of Hong Kong, and a Rhodes Scholar and adviser on strategy for the Oxford Global Society

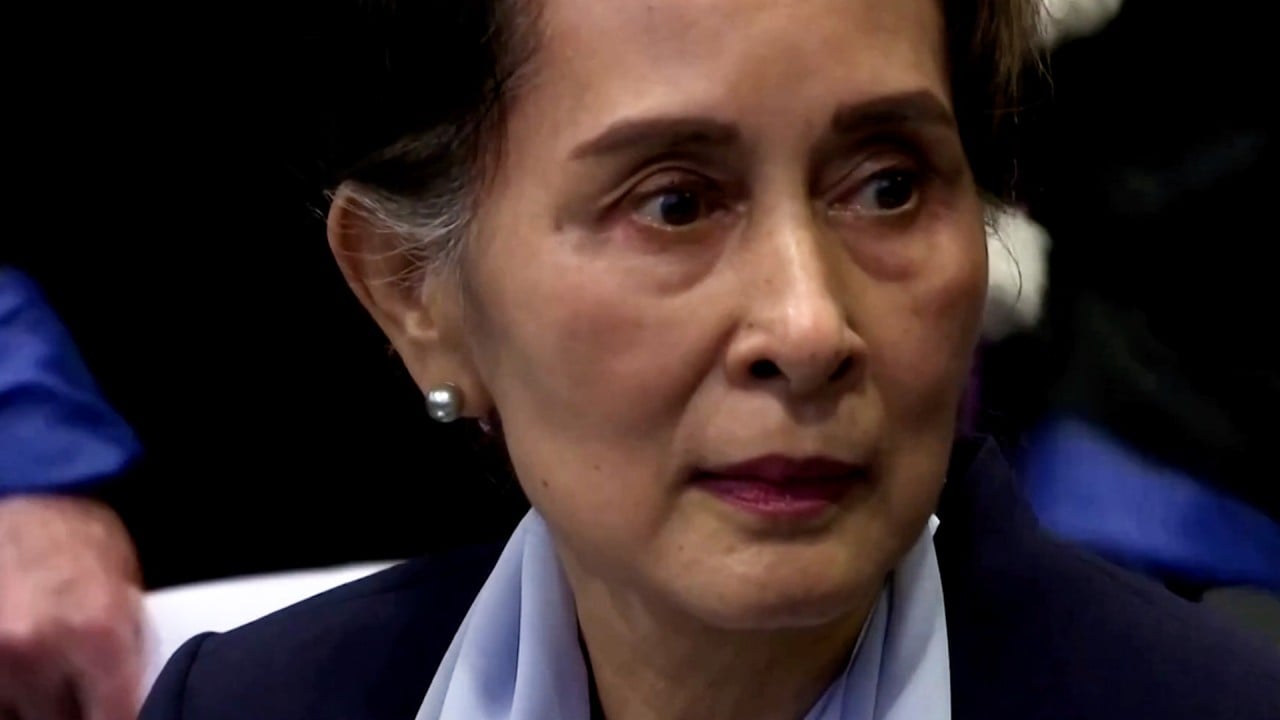

Tidarat Yingcharoen is a Thai-Myanmar academic, educator and politician who is currently the spokesperson and director of the policy centre for the Thai Sang Thai Party in Thailand

.png?itok=bcjjKRme&v=1692256346)