Hong Kong must do much more so working mums can keep breastfeeding

- Even in the sprawling government-funded Cyberport, there is not a single nursing room

- From maternity, paternity and childcare leave, to workplace support and facilities, Hong Kong must realise it takes all of society to raise a breastfed child

Every year, in the first week of August, people in more than 120 countries join the global movement to raise public awareness and support for breastfeeding. This can seem strange when women have been breastfeeding for centuries. Only after I became a mum last year did I realise how hard it is to commit to breastfeeding, especially in fast-paced cities like Hong Kong.

As the theme of this year’s World Breastfeeding Week is to make a difference for working parents, let’s talk about how to make breastfeeding at workplaces work.

Indeed, societal factors such as cultural stigma and workplace policy play a decisive role in how long women breastfeed. While 70 per cent of women worldwide breastfeed for at least a year, less than 24 per cent of women in Hong Kong do.

While close to 80 per cent of women in Hong Kong start out breastfeeding and more than half were still doing so four months later, when most mums returned to work, dishearteningly, by six months, only two in five had continued.

Hong Kong is lagging behind; the World Health Organization’s global targets for breastfeeding rates in 2030 are 80 per cent for one year and 60 per cent for two years.

How can Hong Kong provide a more encouraging, breastfeeding-friendly environment to better protect women’s right to nurse and children’s right to be breastfed?

Studies suggest that workplace challenges remain the most common obstacle. Parents with less than three months of maternity leave don’t breastfeed as long as those with more.

As a first-time mum, I still remember the stress and fear weeks before the end of my maternity leave. Should I quit my job? Would I be able to breastfeed at work when my office doesn’t even have a nursing room? And what if work gets in the way and I can’t take a nursing break?

These questions kept me awake on countless nights. Despite knowing that breast milk is best for my child, I couldn’t convince myself that I could successfully juggle it with work. And I knew I was not alone in thinking that.

Despite the recent progress on maternity leave in Hong Kong, employers should consider providing even longer maternity and paternity leave so new parents are more supported and babies are likely to be breastfed for longer. Studies show that longer paid leave significantly increases breastfeeding initiation and duration.

Aside from offering more generous maternity and paternity leave, employers must also provide breastfeeding-friendly facilities to support women returning to work.

In Hong Kong, although employers are not specifically obliged to provide lactation breaks or nursing facilities, a failure to do so may constitute discrimination against breastfeeding. Yet providing such support is vital in keeping female employees engaged and continuing their breastfeeding journey.

The responsibility of providing a conducive environment for women returning to work lies not only with employers but also with service providers such as facility management companies.

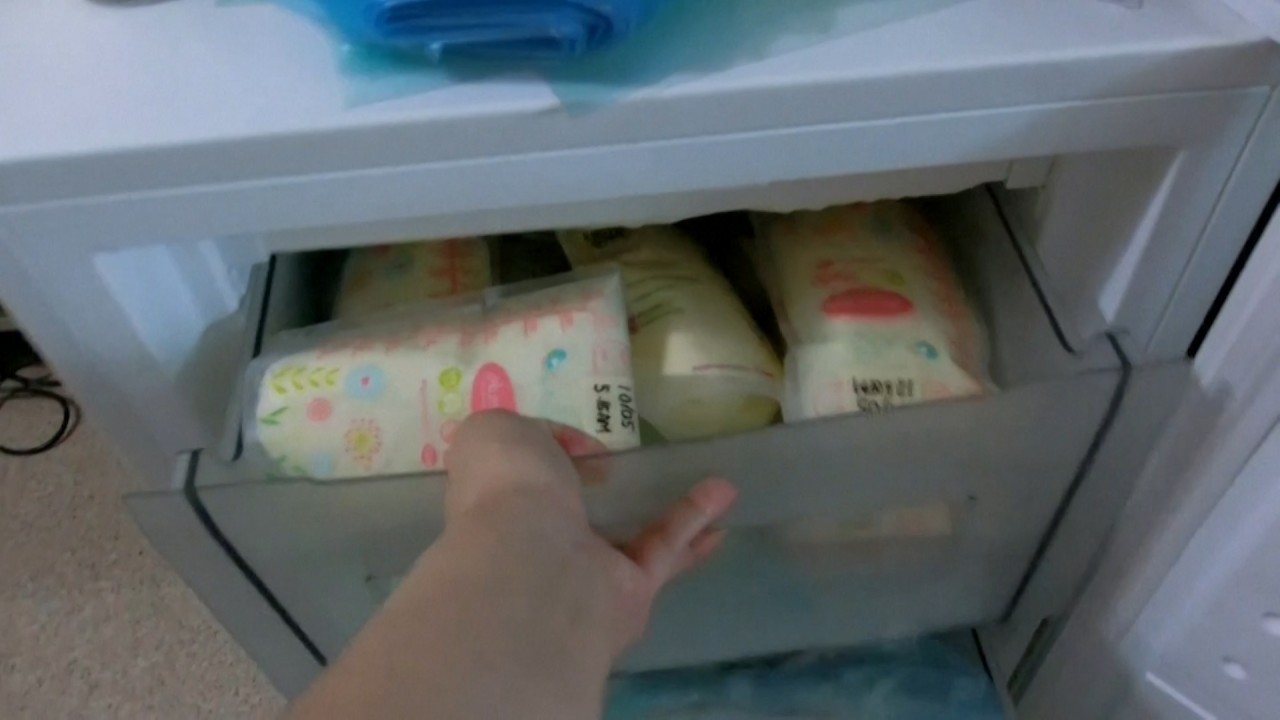

Take Cyberport, where I work, for example. Touted as Hong Kong’s innovation hub, it is home to more than 1,900 start-ups and technology companies. In its 119,000 square metres (1.28 million sq ft) of office space, shockingly, there’s not a single nursing room, so I resort to pumping my milk in a bathroom for people with disabilities.

And yet this is a government-funded community with an ambitious goal to foster positive change. Start-up communities may be dominated by men but they are by no means men-only and their working environment should be inclusive of breastfeeding needs.

Breastfeeding is a mother’s gift to herself, her baby and the planet. It takes the whole society, rather than just mothers, to make it work. Given that we spend one-third of our lives at work on average, leaders in the business communities must step up, offer welcoming workplace policies and a conducive environment to empower women to accomplish this most magical and meaningful mission of their lives.

Summer Reading is a communications professional at an international public relations firm based in Hong Kong