To improve UK-China relations, focus on the grey areas

- The sharp downturn in relations between the UK and China may have caught many in Britain by surprise

- People in both countries do not fully understand each other, with media narratives fuelling mistrust. It’s time to take a step back and explore grounds for peace

What is the proper attitude towards China? Since the British media prioritises domestic politics over foreign policy, it has failed to thoroughly explain the geopolitical competition between China and the United States. Many British people may have been confused by this massive change in attitude at 10 Downing Street. Their daily lives rely heavily on Chinese manufacturing, whether they like it or not.

When I lived in China, my mindset was influenced by Chinese state media, and so I believed that what the Chinese government was doing was justified based on the principle of sovereignty. Over the last 19 years of living in the UK, I have been exposed to higher values of human rights and freedom, which are at odds with China’s emphasis on sovereignty and social responsibilities.

Judging by the Western values, the China government comes across as lagging behind trends in the West. I sensed that the China into which I was born, and where I was educated and worked, was very much like the UK in the 19th century – a nation with a strong economy, but an unfair and unequal society plagued by racism.

I was surprised to realise that even Chinese diplomacy at the highest level has not progressed much when I heard China’s Wang Yi, in trying to convince Seoul and Tokyo to restart cooperation with Beijing at a forum on international relations, voice this opinion: “When we go to America, they can’t tell Chinese, Japanese and Korean apart. We may experience the same in Europe. It doesn’t matter how blonde you dye your hair and how sharp you make your nose, you’ll never become Westerners.”

If I lived in China today, I would give Wang a big round of applause because the mindset on the mainland is one of anger against a Western imperialism predicated on a belief in the superiority of white people. Only few British people are aware of the resentment that persists in formerly colonised countries. Meanwhile, Chinese people is unaware that many British people are ashamed of the dark era of imperialism and are doing their best to fight racism in their country.

Confucianism, which stresses duty and obligation to the family, ruler and state, has had a strong influence on Chinese society for more than 2,000 years. The spirit of the Western Enlightenment did not touch most of mainland Chinese society. Russian communism was a relatively new introduction to China; its history there goes back only over 100 years. Chinese politics today is a mixture of Russian communism, Confucianism and the Communist Party of China’s own exploration, which is not much closer to democracy than it was during the Qing dynasty.

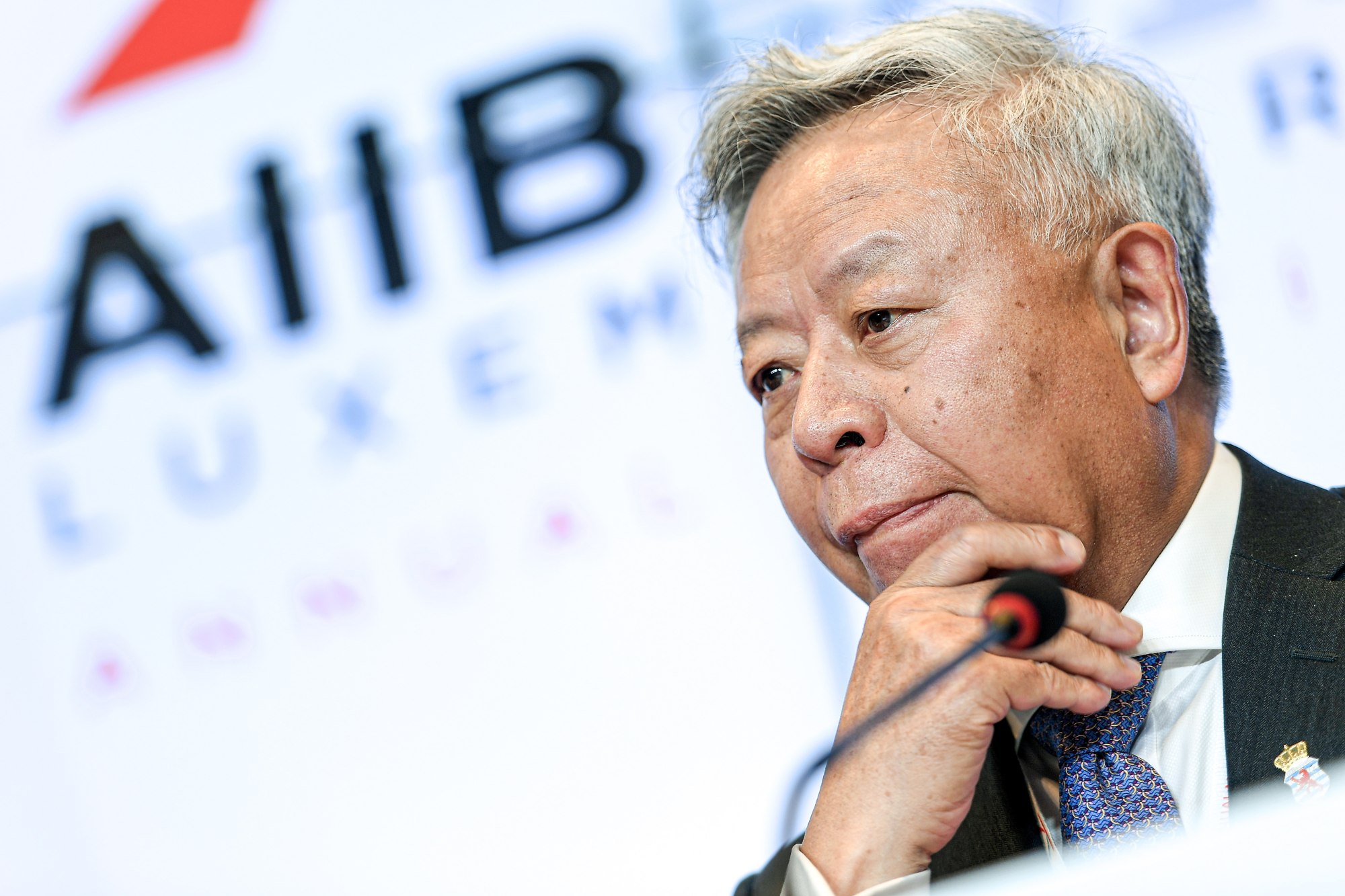

As a first-generation immigrant to Britain from China, I have been very frustrated with the decline in Sino-British relations. I recently interviewed Danny Alexander, former chief secretary to the UK Treasury and now a vice-president of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, for one of my columns.

This interview not only highlighted to me that some of the claims I read in English news media are untrue, but also the extent of the misunderstanding between the West and China.

We should refrain from making extreme judgments. Apart from black and white, there is plenty of grey ground available to stand on in the interest of peace. No matter how much the West takes issue with the Chinese government’s human rights record, it needs to be patient and learn how to work peacefully with this emerging power to tackle climate change and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Yue Parkinson is a freelance writer and bilingual author of China and the West: Unravelling 100 Years of Misunderstanding

.jpeg?itok=IWIemjTe&v=1689818059)