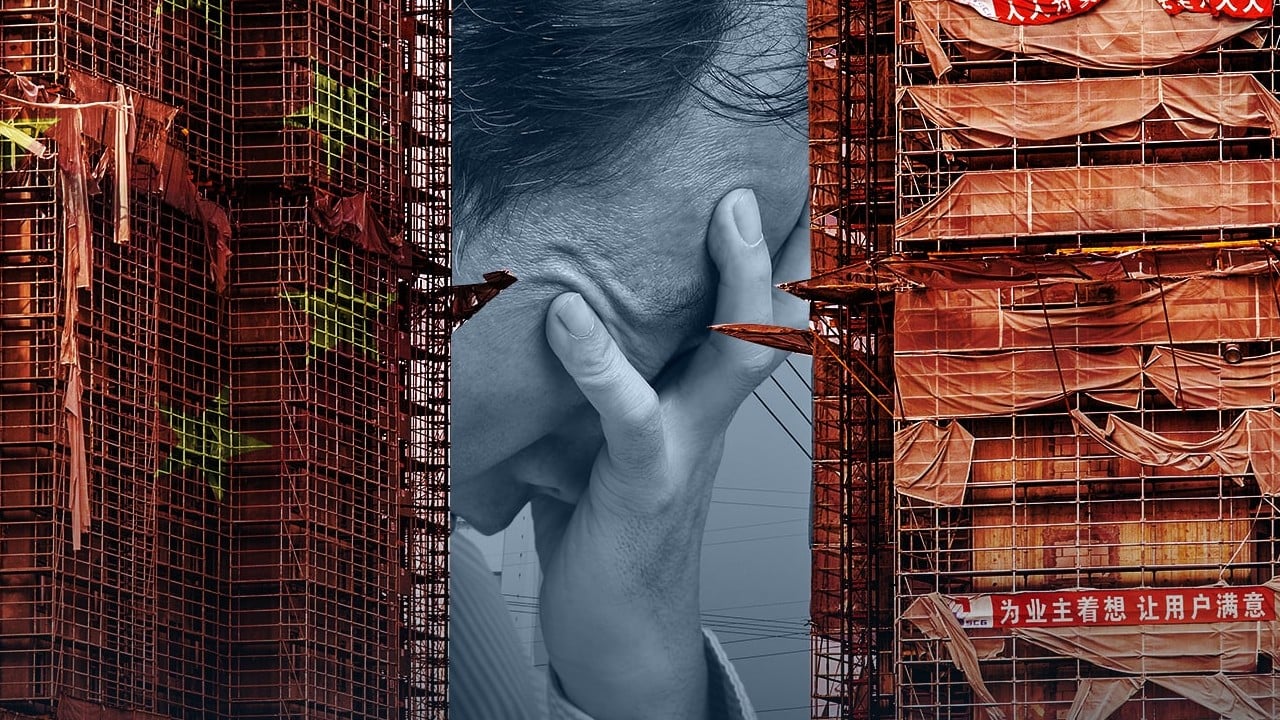

Massive stimulus to revive China’s ailing property market is a fool’s hope

- There are good reasons to believe a far more restrained approach will prevail as Chinese policymakers try to revive a flagging economic recovery

- Even if the government provides meaningful support, the overriding priority is to stabilise the market as opposed to stimulating it too much

In a report published on June 16, Nomura said “markets should curb their expectations for a fast, cure-all package” of stimulus measures to revive the depressed housing market.

There were tentative signs earlier this year that the severe strains on China’s real estate market were easing. Sales and prices began to recover while a partial loosening of curbs on borrowing by cash-strapped developers alleviated the liquidity crisis, but those quickly gave way to a renewed deterioration in the fundamentals of the industry.

In a report published on May 22, S&P Global Ratings predicted sales this year would be more than 30 per cent below their peak level in 2021. Furthermore, it noted that the the property crisis has “entered a new leg”, with sales in upper-tier cities stabilising and transactions in woefully oversupplied lower-tier cities falling sharply.

Ominously, S&P warned that the downturn in third- and fourth-tier cities would “hit a large section of the industry”. If sales in lower-tier cities were to drop 20 to 30 per cent this year, 40 to 60 per cent of rated developers could experience pressure on their ratings. According to S&P, one in four developers are already “brushing against insolvency”.

Will Hong Kong developers’ bets on Greater Bay Area backfire?

Yet, even if the government provides more meaningful support for the housing market, easing measures will remain incremental and conditional. The overriding priority is to stabilise the market as opposed to stimulating it too much. As UBS noted, the focus is on “limiting the downside – more antidepressant than stimulus”.

Jim Veneau, head of fixed income, Asia, at AXA Investment Managers, said intense policy debates over how to respond to the downturn, in a sector that is crying out for reform yet remains a pillar of the economy, work against the implementation of a massive stimulus programme. “If there is common ground, it is to not allow the problems [in the industry] to get even worse,” Veneau said.

Second, China is not as financially stable as it was in 2008, when it could afford to spend its way out of trouble. China’s total debt-to-gross domestic product ratio hit a record high of nearly 280 per cent in the first quarter of this year, nearly twice the level in 2008, according to Bloomberg data.

While this could be viewed as procrastination, a massive stimulus programme could backfire if it is taken as a sign that Beijing is more worried about the housing market than previously assumed. “It could be perceived as an act of desperation as opposed to restoring confidence,” Veneau said.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory