Hong Kong can ensure artificial intelligence remains a force for good

- The steady rise of AI technology has left governments, industries and institutions scrambling to catch up and establish rules of the road

- As a knowledge-based economy, Hong Kong can lead the way in building a regulatory framework that limits the harmful impact of AI and maximises its benefits

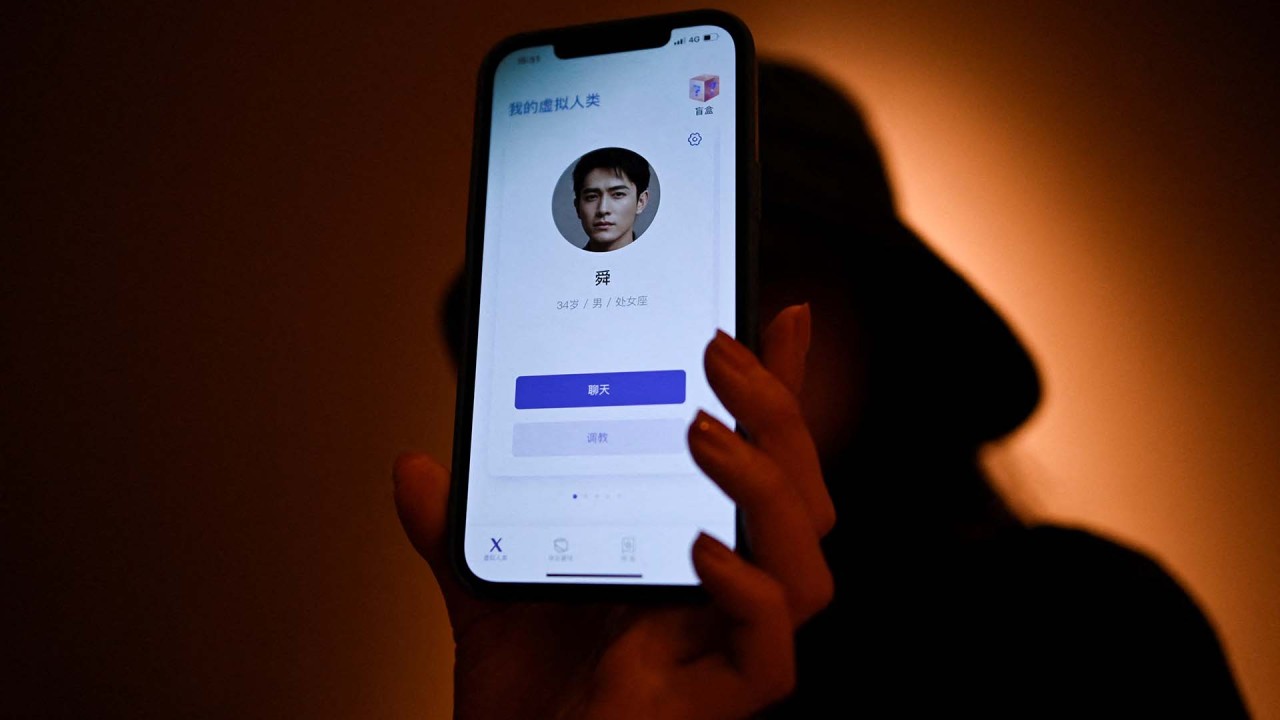

Would you want to talk to a digital version of your loved one after they have died? The idea may sound like something out of the dystopian sci-fi series Black Mirror (and as it turns out, the idea did feature in a 2013 episode). But it’s not entirely science fiction.

Using artificial intelligence, the California-based company HereAfterAI lets people “talk” to loved ones who have passed on, though it’s unclear how realistic the experience is at the moment. But as this kind of technology improves, one can expect a range of views about how society should address it.

AI tools have been quietly proliferating in most sectors. But ChatGPT has driven home just how swift that progress has been. Indeed, incremental advancements tend to go unnoticed until a truly disruptive technology emerges.

And so while a virtual replica of one’s departed relatives might be an edge case, it is indicative of the potential challenges that may arise as various industries adopt AI.

Educators have already reported using ChatGPT to generate essays that they would consider acceptable for a university writing assignment. This raises questions about the purpose of education and how it should be achieved.

There is a growing case for increasing digital literacy requirements in primary and secondary education. If future workers will be reliant on AI assistants, it makes sense to make basic coding understanding an educational requirement, as with literacy and numeracy.

There is also a strong case for Hong Kong and other Asian universities to allocate more funding to liberal arts programmes. In a world where AI can carry out remote tasks, the role of human operators will increasingly be to make value judgments.

But unlike traditional media, or even social media, the average user can’t necessarily source the information or understand how the error cropped up. In countries that are seeing declining trust in media, it’s unclear what the public will decide to put their faith in.

For now, Hong Kong appears underprepared. The city has no specific laws or regulations governing the use of AI in Hong Kong. Singapore is moving in that direction by convening an advisory council on the ethical use of AI, and Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry last year released guidelines for AI governance.

Hong Kong could also be well positioned to develop guidelines for the use of AI in financial services firms. For example, there should be agreed-upon transparency standards that balance IP and trade secret concerns with consumers’ right to understand how their data is being used.

Consumer protection more broadly could also be a good place to start. The Hong Kong Consumer Council called for such legislation in September amid widespread public worries about how consumer data is being used.

These are good first steps that should become part of a more comprehensive approach, bringing together experts from different fields in industry, academia, and government to understand the broader social effects of AI, and the best ways to adapt.

Researchers at Kyoto University modelled the impact of AI and robots on human industry and employment in the city by 2050. They believed that livelihood problems could be solved if society was incentivised to focus on human well-being rather than monetary KPIs.

It’s a tall order, but in the aspiration of working towards a collective vision of how AI should benefit society, Japan presents one potential model of how Hong Kong can address its AI challenge.

Colleen K. Howe is a programme associate at the Asia Business Council