Why the Fed should go easy on the world economy in 2023

- It is consumers who pay for the cost of the pandemic and the energy price spike. It is also consumers who drive economic growth

- With the world economy headed for tough times and US mortgage rates hitting a high, the Fed shouldn’t inflict higher rates and greater pain

The problem is that central banks have lost patience with inflation and the cupboard is bare in terms of what governments can afford to spend on reflation.

There are worries about job security too as companies seek cost savings, adding extra pressure as unemployment levels start to creep higher. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reports that the unemployment rate in the OECD area was stable at 4.9 per cent for September, slightly above its low point of 4.8 per cent recorded in July 2022, but the odds are that the jobless rate will rise a lot more as global headwinds intensify and business confidence dives.

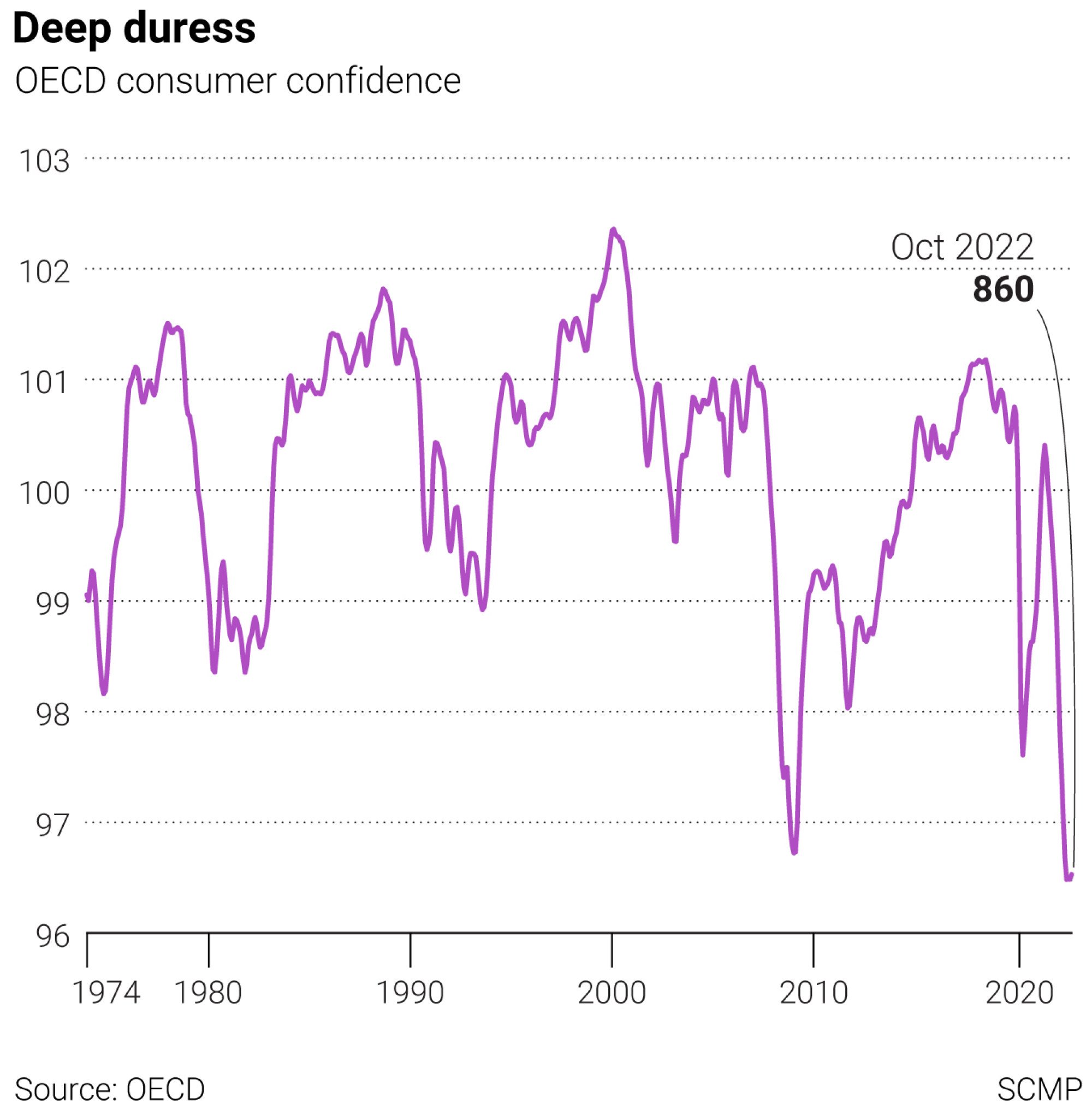

It’s no surprise to see consumer confidence levels showing signs of deep duress. For the 38 OECD member states, consumer optimism is close to an all-time low. It’s even weaker than the lowest points reached during the 2020 pandemic and after the 2008 crash.

The main worry for consumers is the rising cost of credit and the impact of higher mortgage borrowing costs on the housing market. Property values and financial perceptions could be hit very hard.

‘Finances are very tight’: how consumer confidence has tanked in China

Some countries will be more susceptible than others where consumers account for a larger share of aggregate GDP. In the United States, one of the world’s most consumer-driven economies, consumer spending accounts for up to 70 per cent of national output and can play a vital role in recovery expectations. With US mortgage rates hitting their highest level in nearly 20 years, there will be severe consequences for the economy as consumers are forced to cut back, especially with outgoings for fuel and energy going up at the same time.

With the right policies in place, global policymakers can limit the severity of the downturn and the odds are the central banks will need to give way first. Consumers need a helping hand and the US Federal Reserve should lead the way with easier monetary policy next year to lend a hand to global recovery.

David Brown is the chief executive of New View Economics