Xi Jinping is serious about securing tech, talent and a modern military for China in the next five years

- Xi Jinping’s references to revolutionary spirit underlines his resolve to barter China’s vast capital and market for tech cooperation to break the US chip ban, and attract talent, including for military modernisation

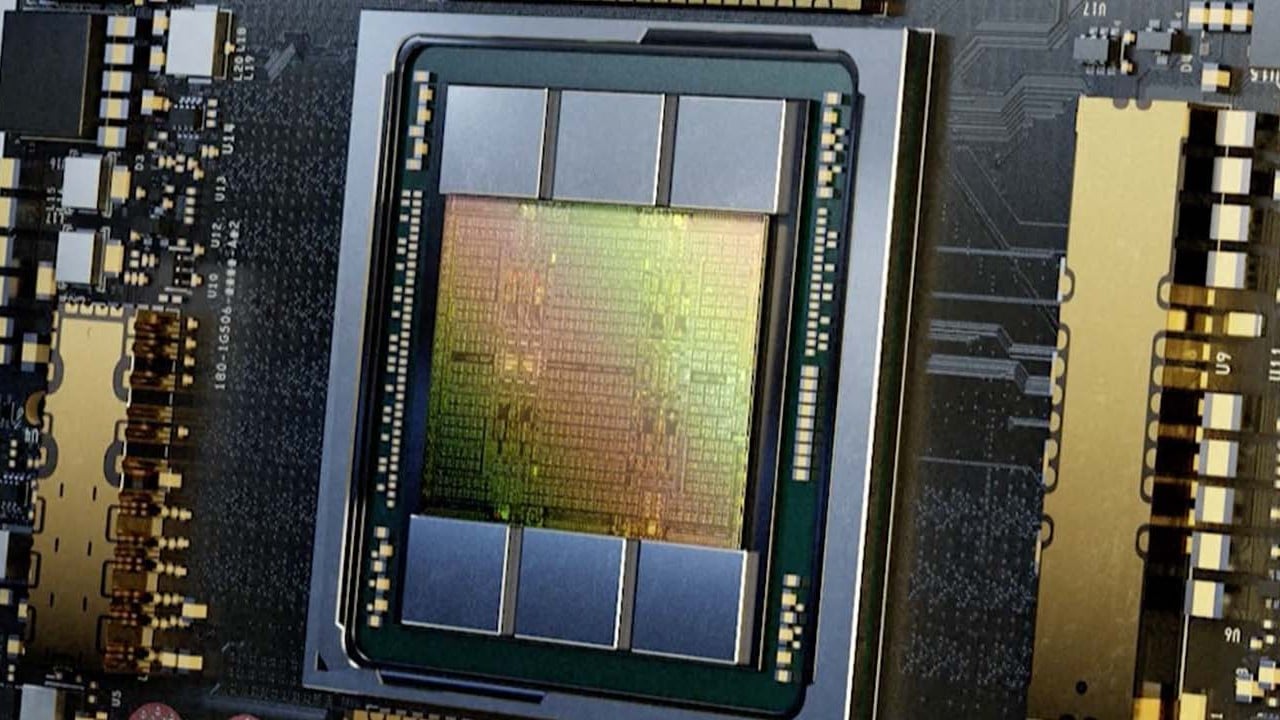

Central to his vision is the breaking of the technological containment of the United States.

Biden’s tech policy is fundamentally an America-first policy – if successful, US companies will be triumphant, likely at the expense of allies and foes alike.

But when China accounts for 40 per cent of global chip demand, non-US chip makers are in a dilemma. Although restructuring is painful, global chip makers may find a strong incentive to remove US technology from their supply chains to keep China as a customer.

The first mover will win big. China may strategically invoke such competition by offering quick-moving countries wider access to the lucrative Chinese technology market. In the next five years, China’s attempt to partner technologically with Europe and the rest of Asia is only logical.

Unlike with Soviet Russia in the Cold War, Chinese talent and capital can reach virtually any corner of the world. In the next five years, Chinese hi-tech manufacturers will venture overseas and deepen their supply roots in the European Union, East Asia and other markets where access to US technology and talent remains open. Biden’s chip ban applies only to those on Chinese territory, not to Chinese companies overseas.

US-trained talents from other developing countries may find China’s enormous industrial funding for semiconductor start-ups alluring. Before the pandemic, about 37 per cent of US-trained graduates who majored in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) were international students. There is no default winner in a global chip talent war.

Monetary incentives oil the wheels of capitalism. In the talent war, China seems to be in the driver’s seat for now.

The pillars of Xi’s economic vision are technology, talent and the military. He is ready to get his way by trading on China’s capital and markets. Xi’s gamble with China’s fate is of global consequence. If the first week of his third term says anything at all, it might be that where there is a will, there is a way.

Shirley Ze Yu is a political economist and a senior practitioner fellow with the Ash Center of Harvard Kennedy School