In the global power struggle, India is determined to remain a friend to all and to none

- In an era of shifting power dynamics, India stands to benefit from a policy of both non-alignment and multi-sided engagement

- Yet as geopolitical hostilities persist, remaining focused on national interests and resisting calls to take sides will take considerable skill

It’s becoming clear that we are currently witnessing the transition from a US-led liberal order to something that is yet to be determined. And perhaps there is no country so fortunately positioned as India to engage with all sides of this power struggle.

It is also a member of BRICS, has both Russian ties and friendly American relations, maintains communication with China and keeps up with its Japanese, French and Israeli engagements.

It is uncomfortable for Western partners to see New Delhi’s concurrent Eastern orientation. But such multiway engagement combined with non-alignment should be understood in the context of India’s various regional concerns, including China’s rising influence, growing Russia-China relations, and China-Pakistan counterterrorism cooperation.

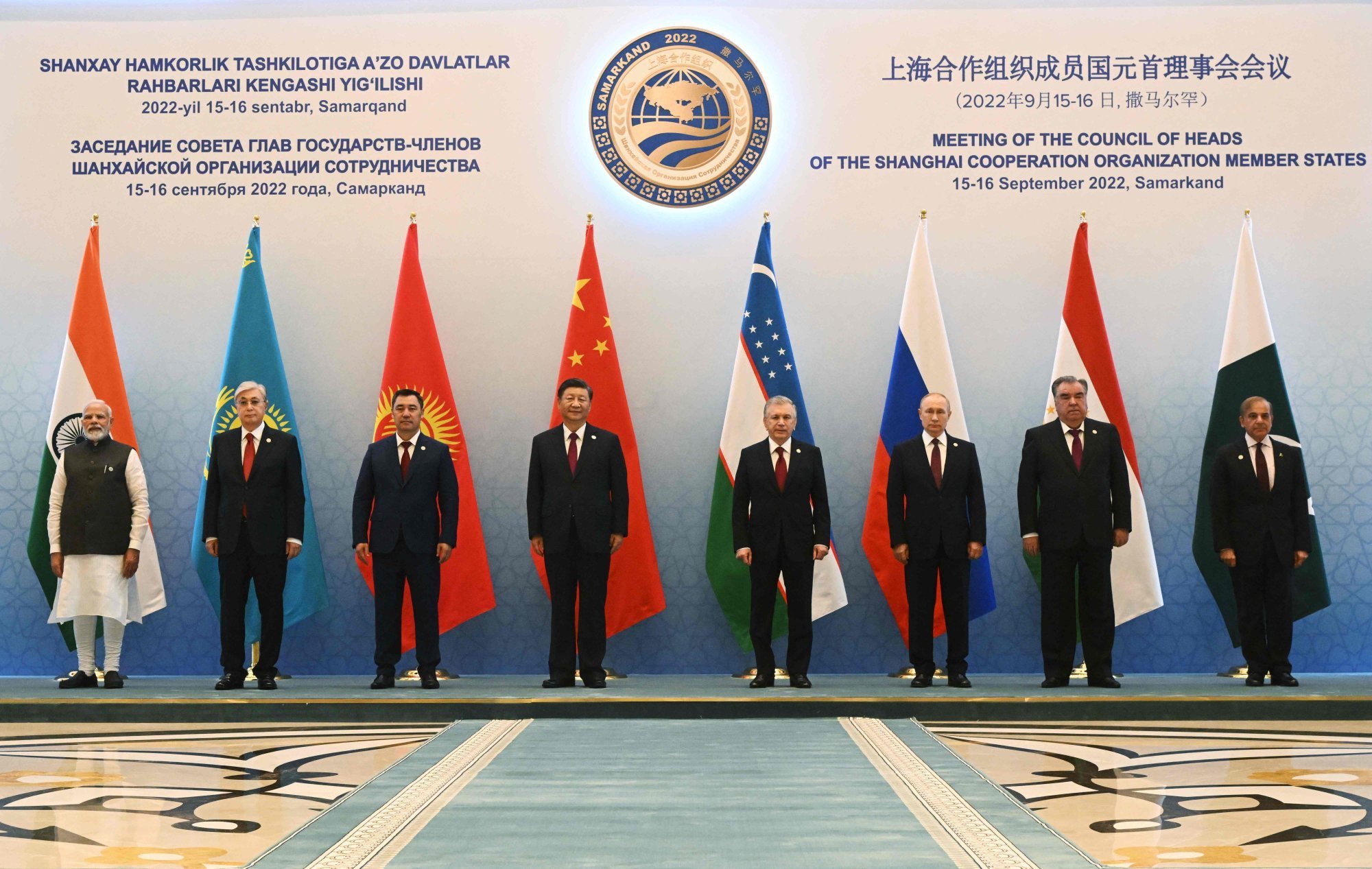

India’s busy schedule in September signals it is intensifying its strategic diplomatic outreach. The Quad senior officials’ meeting, the IPEF ministerial discussion, the SCO Samarkand summit, and the 2+2 mini-laterals with the United States and Japan were among the highlights in India’s calendar.

Indian Trade Minister Piyush Goyal cited worries over digital trade, the linkage of environment and labour to trade, and the responsibilities of developed world as reasons for New Delhi’s decision to wait for further clarity on the binding commitments.

The Eurasian SCO is the largest regional organisation in the world, representing almost half the world’s population and nearly 30 per cent of global GDP, if taking into account purchasing power parity. The group covers multiple areas of cooperation, from security to economy.

Emerging from the 1996 Shanghai Five comprising China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the SCO was founded in 2001 with the addition of Uzbekistan, expanding to include India and Pakistan in 2017, and Iran this year.

Although the SCO’s role as a counterweight to the Western-led world order is disputed, the group denied the US observer status in 2005 and called for an end to US military presence in the SCO sphere.

The meeting of the heads of SCO member states on September 15-16, which mostly focused on the use of national currencies for trading, was quite fruitful for India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had a series of productive multilateral and bilateral engagements on the sidelines of the summit.

Modi did however meet Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who joined the summit as a special guest. Türkiye, like India, holds a unique position in both the West and East. During their meeting, Erdogan and Modi reviewed recent gains in bilateral trade and discussed ways to deepen cooperation in diverse sectors.

This is a welcome development. As C. Raja Mohan, one of India’s leading strategic thinkers, wrote in a 2021 Indian Express op-ed, “there is no escaping the fact that Türkiye is determined to rewrite the geopolitics of Eurasia; that is a good reason for India to explore a more purposeful engagement with Türkiye”. Sooner or later, both sides will recognise the other’s potential.

Ukraine crisis: Türkiye and India may make the best peace brokers

With all that said, notice that even if India benefits from pursuing an independent policy, or indeed from partnering on all sides, the argument that it is better to be inside than out is one that evidently requires intricate diplomatic manoeuvres.

Imagine: if India gets stuck down a dead end by taking sides in an international environment characterised by division and confrontation, how could it then astutely manage to win more space to pursue its own national interests?

Dr Duygu Çağla Bayram is an Ankara-based India specialist