US-China trade truce is needed to lift the global economic gloom

- Recent signs that the punishing tariffs in place for several years may be reviewed have brought hope

- On top of easing trade tensions, China’s shift towards nurturing domestic consumption should also be complemented by a renewed US focus on manufacturing

A resolution is long overdue and it could pave the way for better relations and stronger bilateral trade flows. With global economic confidence on the back foot, it’s the moment when the world’s biggest powers could heal their differences and put the needs of the global economy first.

Once again, uncertainties are piling up, global growth is slowing and world trade flows are at risk. It’s crunch time and the US and China have an opportunity to stabilise the situation.

The latest data, for March, from the Netherlands’ Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis shows that global trade momentum slowed fairly sharply in the first few months of 2022. The annualised rate of world trade growth, a moving average over three months, reached only 3 per cent in March, compared to 13.2 per cent annualised growth as recently as January.

The domino effect of Trump’s tariffs against China in 2018 resulted in a sharp contraction in world trade flows and the annualised three-month average rate of contraction dipped to as low as minus 7 per cent in January 2019. Correspondingly, global GDP growth dropped from 3.7 per cent in 2017 to 2.9 per cent in 2019 as increasing trade protectionism dragged on business activity.

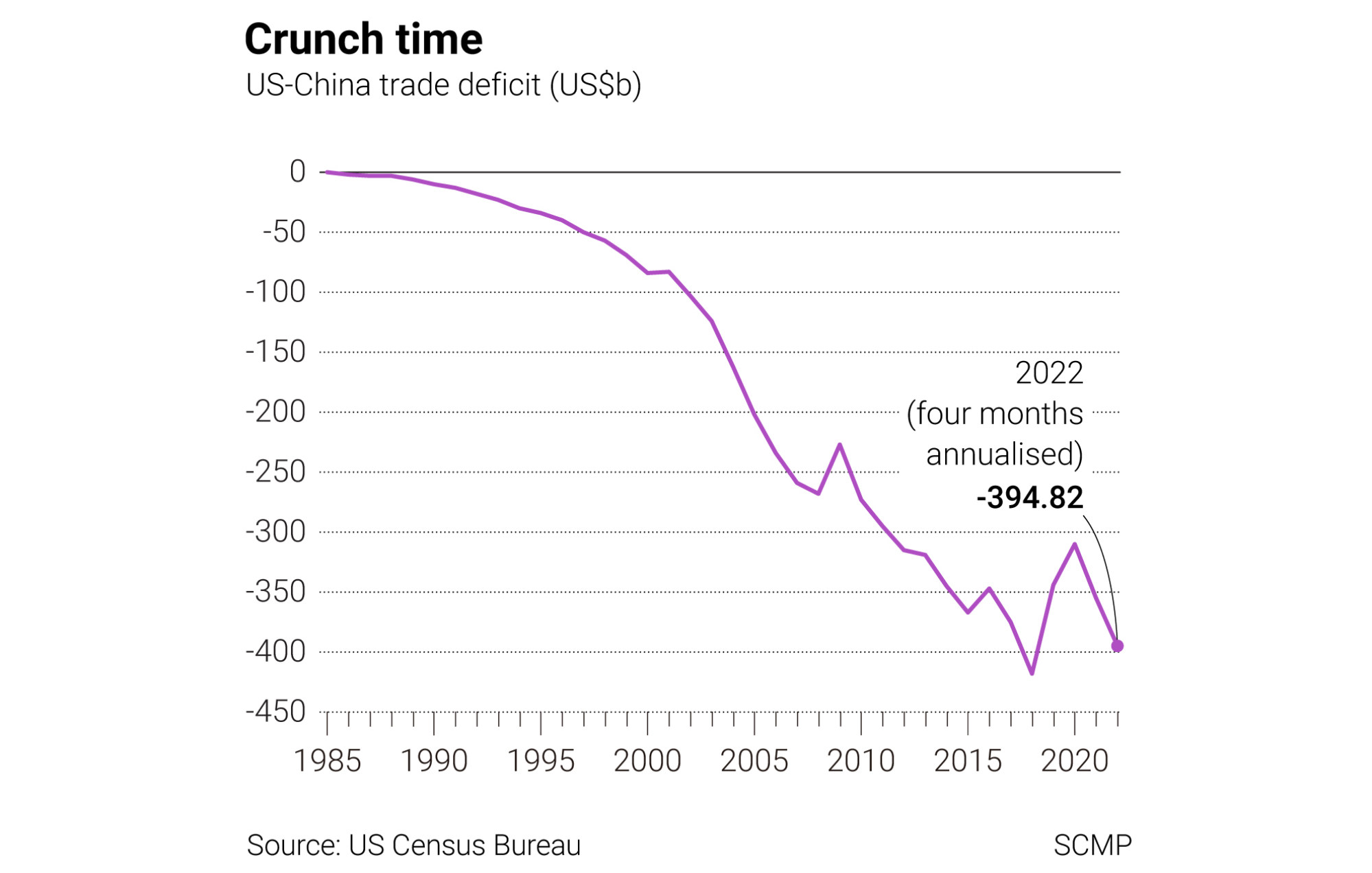

From the US perspective, Trump’s actions accomplished the desired effect of reducing the deficit with China from a peak of US$418 billion in 2018 down to US$310 billion in 2020, but at a significant cost to the global economy. More recently though, the US-China trade deficit seems back on trend and could be returning to over US$400 billion this year.

This could draw in more import demand from domestic consumption, helping to moderate trade tensions with the rest of the world and hopefully with the US in the process.

On the US side, macroeconomic policy adjustments need to counter domestic demand leaking abroad into imported consumer and business goods, with incentives encouraging more investment in US manufacturing, especially with a bigger export focus.

What both US and China get wrong on economic policy

This would be hard to orchestrate under normal circumstances for a market-driven economy like the US’, but it is even more challenging when global headwinds are rising and aggressive US interest rate tightening is bolstering the dollar and squeezing export competitiveness even harder.

If the US and Beijing can break the deadlock on the trade war, the world will be the winner. It could mean the difference between make or break for global recovery in 2022.

David Brown is the chief executive of New View Economics