Traditional Chinese medicine could be just what the doctor ordered for Hong Kong’s future

- With its R&D capabilities, the city could play a key role in making TCM more cost-competitive. Embracing it could help make the city a central figure in the Greater Bay Area and national strategic planning

I can predict with some confidence that we will hear even more about it soon. Therefore, I think it is important for more people to have an accurate understanding of what TCM is and what it is not.

I think there is a bit more to the story. In fact, the Chinese government and people are very well-informed about the importance of comparing TCM to placebo. They understand that the placebo effect is powerful, and that the efficacy of modern medicines is measured against that baseline. Two anecdotes should demonstrate this point.

In 1988, Shanghai experienced a serious epidemic outbreak of hepatitis A. Around 300,000 people were infected from eating raw clams that came from polluted waters. Although the overall death rate was low – only 47 cases, or just 0.015 per cent – the public was still in a frenzy.

Among the reasons given for providing patients TCM was that it would help ease their psychological burdens. This reasoning has been repeated in state media, so there can be no doubt about the intent behind the move. To this end, TCM can be used alongside tai chi, massage, listening to music and aromatherapy on a truly impressive scale.

I have heard two opposing schools of thought from local Shanghainese as far as the strength of TCM’s effects against Covid-19. The first states that ethnic Chinese people benefit from TCM the most – one must believe in the medicine for there to be an effect, and Chinese people are the primary believers in TCM.

The other states that foreigners can benefit even more from TCM because many Chinese people are jaded, whereas foreigners encountering TCM for the first time might be more willing to believe. Nevertheless, the two schools of thought apparently agree that placebo is a feature of TCM.

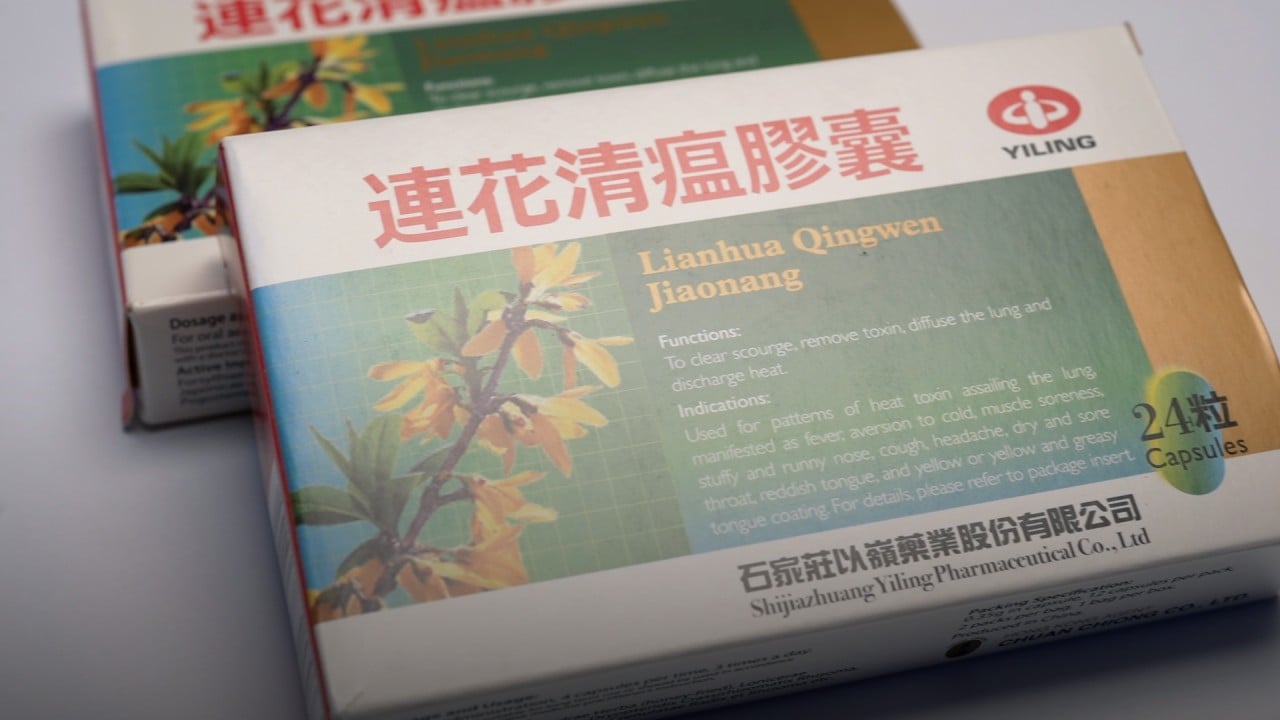

Two boxes of 36 capsules, following the recommended dosage of 12 capsules per day, would last a person for six days. I do not claim to know how much the recent mass distributions cost the respective governments – at least 8 million boxes in Shanghai were reportedly donated by the manufacturer – but at list prices, it would cost at least 1.3 billion yuan to supply the residents of Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Compared to placebo treatment, this is very expensive. TCM primarily comes from medicinal plants, which need to be grown, harvested, processed into extracts and packaged into capsules. All of these processes require labour and resource inputs, which drive up the cost of the final product.

However, as with all technologies, research and development can raise efficiency and bring down costs. This is an area where Hong Kong arguably can play a vital role. Hong Kong has leading Chinese medicine faculties at Baptist University, Chinese University and the University of Hong Kong, which enable the city to conduct cutting-edge research and development.

Patrick Jiang is an honorary research associate at the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong