What price zero Covid? We need to know the cost to Hong Kong

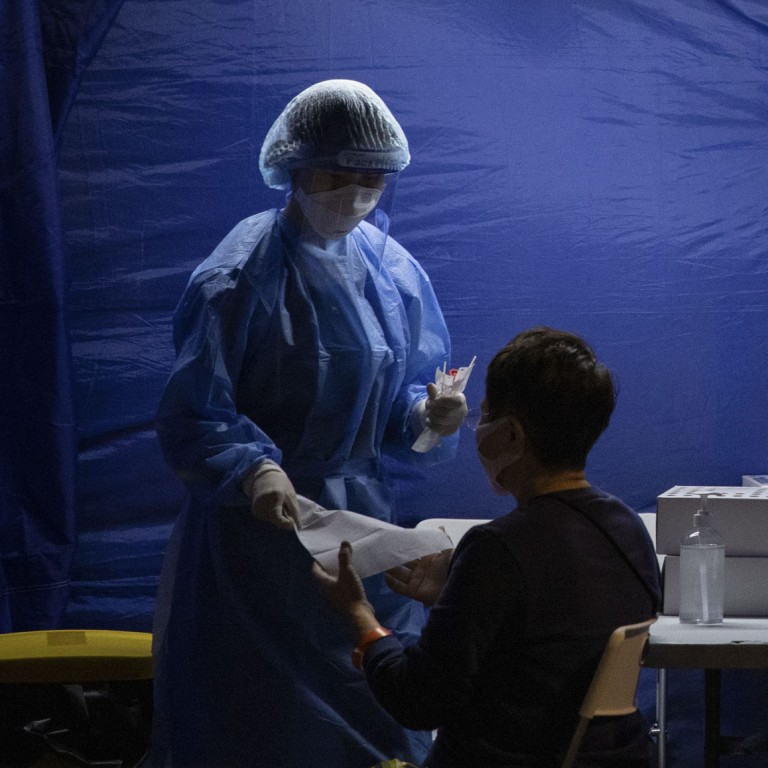

- The government’s panic-driven effort to attain ‘zero Covid’ is straining our hospitals and driving businesses big and small to the point of collapse

- Hong Kong needs a serious cost-benefit analysis of the arguments supporting the policy amid evidence of serious, long-term harm being done

Ready access to vaccines and the fact Omicron appears less lethal than its predecessors means the danger of our hospitals being overwhelmed by gravely ill people has disappeared.

But where is the much-needed cost-benefit analysis that weighs the increasingly flimsy arguments in support of “zero-Covid” against the mounting evidence of serious, potentially long-term harm being done to our community and our economy?

It would be unfair to claim there is any deliberate attempt to fudge the evidence of harm. But in the absence of interest in bringing that harm into sharp focus, a proper cost-benefit analysis remains impossible.

Beyond such troubling anecdotal evidence, look at the Census and Statistics Department’s latest figures on Hong Kong retail sales. Compare sales for the first 11 months of 2021 with those for the same period in 2018 – the most recent “normal” year – and you see a 27.4 per cent fall, from HK$440.3 billion to US$319.6 billion. This probably means thousands of shop closures and tens of thousands of jobs lost.

Yet this alarming array of anecdotal evidence is not reflected in the macro data being reported by Chan. This has been particularly puzzling in our Official Receiver’s Office. Bankruptcies soared to 26,900 in 2002 after the dotcom crash and 15,800 in 2009 after the global financial crash, but last year they sagged to a 20-year low of just 7,200.

Hong Kong finance chief urged to issue more e-vouchers to rescue economy

Since it is harder to shut down a company than start one, I am sure many have fallen into a “zombie” state, with many bosses of small and medium-sized firms falling back on savings. What Chan is describing as evidence of recovery is more likely evidence of companies stumbling along on life support.

The International Labour Organization calculates the equivalent of 125 million jobs were lost last year because of the pandemic, with a further 52 million losses expected this year. It also says an additional 30 million adults have fallen into extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic.

It is improbable that such acute stress has not been felt with equal force in Hong Kong. But the absence of relevant data or a government determination to understand clearly what harm the economy is suffering leaves us in a fog.

It also allows the administration to pre-empt a cost-benefit analysis that will enable us to judge whether the “zero-Covid” approach is still justified. Sadly, Chan’s upcoming budget is unlikely to shed much light.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view