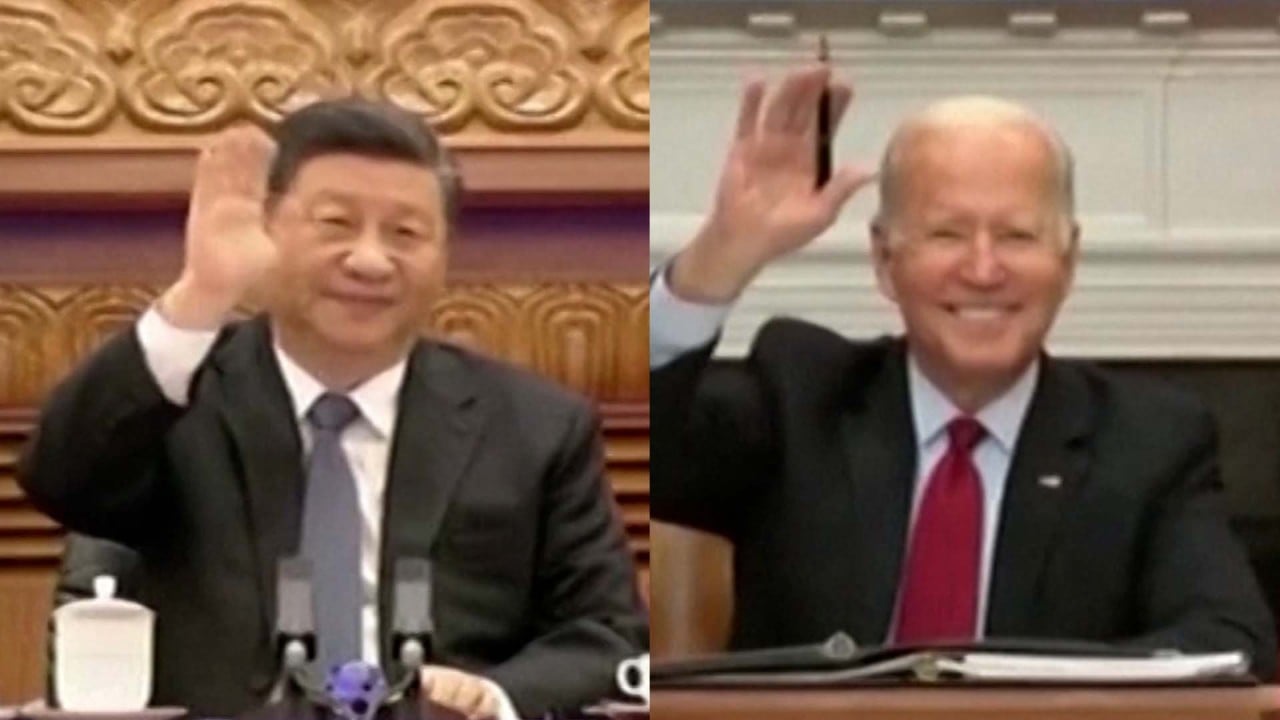

Biden is running out of time to implement his China policy. First he must decide what it is

- The US president has made it clear he wants to compete with China, but while his rhetoric has united Democrats and Republicans, it has done little else

- With no China expertise within his team or any chance to meet Xi face to face, Biden’s China policy is suffering and his window of opportunity narrowing

Washington Post columnist Henry Olsen recently praised Biden’s effort to foster an allied approach to China as “refreshingly coherent and competent” and a rare bright spot in a largely disappointing first year.

While consistent messaging on China is certainly an improvement over the Trump era, it hardly counts as a strategy. In fact, Biden’s approach to China thus far consists mostly of question marks.

But it does not appear that Biden was responsible for the resolution of either case. On the contrary, the administration maintained the Justice Department acted without political interference to reach the agreement with Meng and denied any connection with China’s decision to release the Canadians.

I am not surprised that Biden has thus far been an ineffective steward of China policy. In the decades that I worked adjacent to him through my work at the US Library of Congress, I never knew him to be particularly interested in or knowledgeable about China.

And as much as he and his administration have emphasised their concerns on the challenges posed by China, nowhere among his advisers do I see any real China expertise. Neither Secretary of State Antony Blinken, national security adviser Jake Sullivan, or even Ambassador Burns have much expertise dealing with China. They are all European experts, which reflects Biden’s priorities in the Atlantic over the Pacific.

It’s also unclear if Biden is consulting any outside experts. Throughout the more than 70 years that I have called the Washington, DC area my home, I have watched successive American presidents and policymakers lean on China scholars to guide their understanding and influence decision-making.

These scholars include some of the most celebrated Sinologists of the 20th century, including John K. Fairbank, A. Doak Barnett, and Ezra Vogel. Even the Trump administration found its own coterie of China experts to consult, including Michael Pillsbury.

Will Biden’s election woes affect approach to China?

The outcomes of the looming 2022 midterm elections may determine the fate of the Biden presidency. If Democrats lose their narrow hold on Congress, it will be virtually impossible for the president to pass anything meaningful and he risks becoming a lame duck.

Chi Wang, a former head of the Chinese section of the US Library of Congress, is president of the US-China Policy Foundation