China’s use of maritime militia demonstrates its control over South China Sea

- Tensions over the 200 Chinese vessels moored off Whitsun Reef have again put the spotlight on the range of capabilities Beijing employs to maintain effective control of the increasingly contested and militarised waterway

Just as the world watched the saga of the Evergreen container ship in the Suez Canal, at the other end of Asia another major maritime waterway was witnessing its own worrying events.

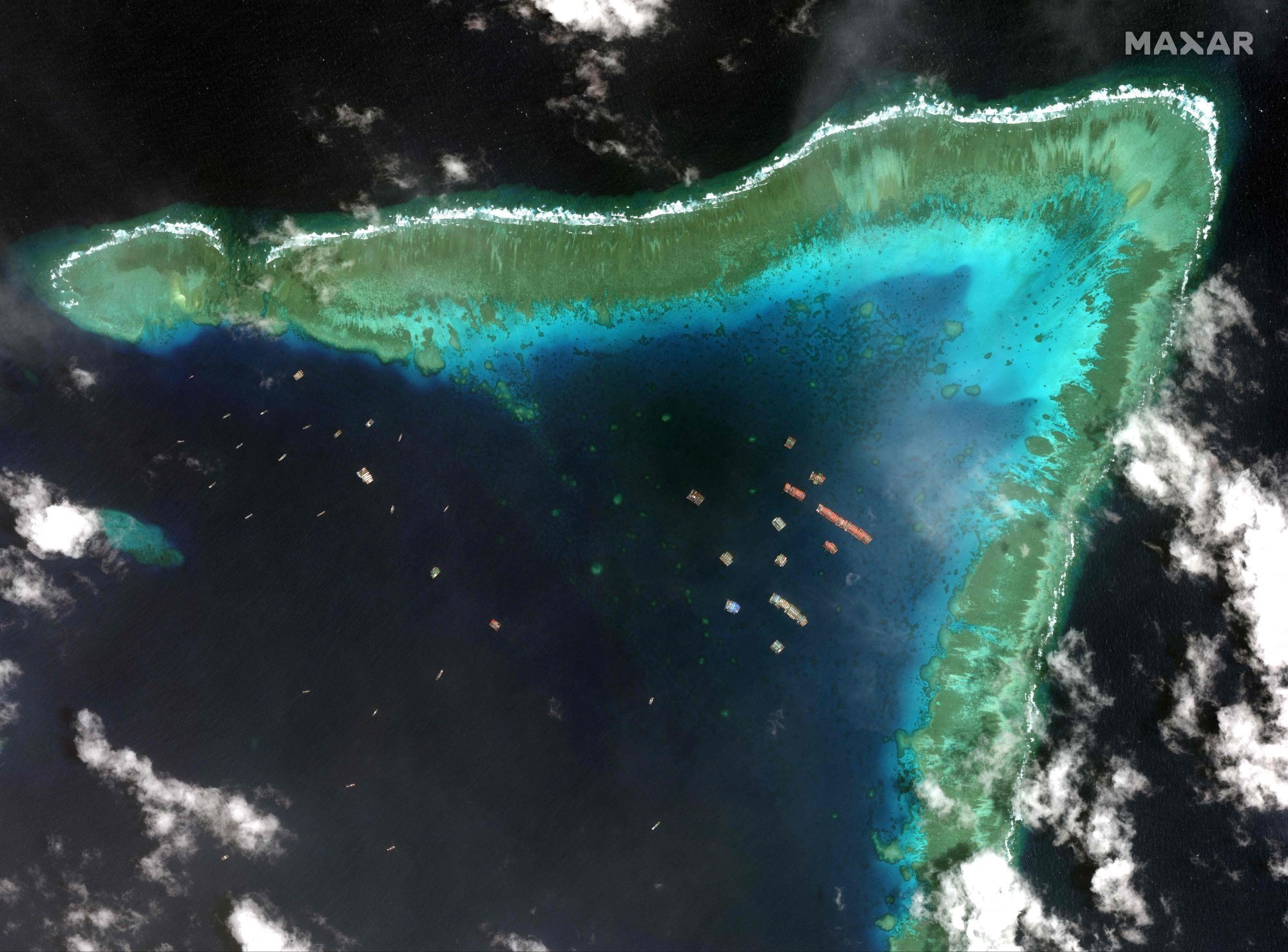

Beijing has denied the charge, with the gathering explained away as fishermen sheltering from poor weather. But this is implausible; images show that conditions in the area are fine, and it is highly unlikely that so many commercial fishing vessels would neatly line up for several weeks, idle and not earning any revenue.

The Chinese vessels were moored just off Whitsun Reef, a nearly entirely submerged sandbar. Unlike some 50 other features in the disputed Spratly Islands, Whitsun Reef is currently unoccupied and comprises just a low-lying, right-angled reef in the sea.

Still, there is strategic value to having control of the reef. Until recently there was nothing more than a low-tide elevation there, visible only when the waters receded. Now, there appears to be a small, low-lying feature that exists even at high tide.

Further, Whitsun Reef is the easternmost feature in a grouping called Union Banks, home to four Vietnamese-occupied features and two Chinese-occupied features.

The Union Banks have for decades been rich fishing grounds, particularly for Philippine fishermen. Controlling access to the atoll would enable greater management of fishing rights, as well as an ability to deny rivals freedom of navigation through the features.

The result, after much negotiation, was that China was left in de facto control of the shoal and Chinese fishermen continue to plough the waters unhindered, while Philippine fishermen are often refused access.

The Chinese vessels have now dispersed: Manila noted that 44 vessels remained at Whitsun Reef on March 29, with 115 vessels having moved to the nearby Kennan Reef in the Union Banks, 45 to the Philippine-occupied Thitu Islands, with another 50 at three other Chinese-occupied features.

But the episode reflects the importance of China’s maritime militia in exercising effective control of the South China Sea at particular locations and times. Beijing has been adept at using the range of capabilities available, from naval vessels to coastguard ships and the maritime militia.

With a fleet that outmatches any individual rival, it is able to bring a mass of vessels together to preclude access to other civilian, paramilitary or military claimants at any one time.

It is difficult for rivals to respond effectively, as no state wants to be seen to be the first to use force, and replying to civilian vessels with military force is disproportionate and escalatory.

China’s rivals are thus turning to other powers to help them, particularly the United States. This has seen the US counter China’s grey zone tactics with the deployment of the Coast Guard to the Western Pacific, enabling the US to utilise a non-military capability in response.

Washington wants to ensure freedom of navigation, but China is showing that increasingly, it is able to use a range of capabilities to exert at least temporary control on one of the world’s most important maritime trade routes.

Christian Le Miere is a foreign policy adviser and founder of Arcipel, a strategic consultancy