How the US-China knowledge gap is hurting American diplomatic efforts

- The top Chinese diplomat speaks fluent English, but the US Secretary of State does not speak Chinese. Their meeting in Alaska highlights a US-China gap

- It is worrying that as the US and China move towards a ‘new cold war’, the next generation of US policymakers may be even less well-informed about China

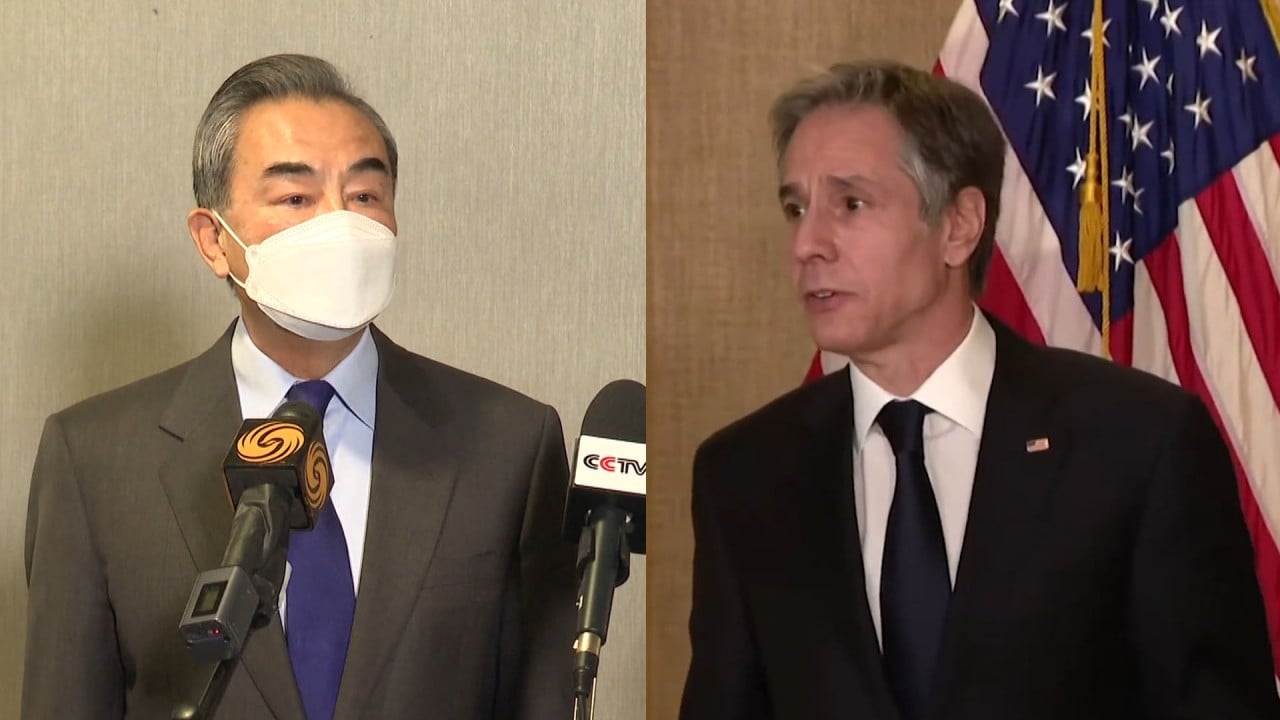

Yang’s now-famous speech accusing the US of hypocrisy was delivered in Chinese, but he noted in English after finishing, in one of the meeting’s lighter moments: “This is a test for the translator.” Yang studied in Britain and speaks fluent English; in the past, he has criticised translators’ work.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken agreed that it would be a challenge for the translator, but unlike Yang, he would have no way of gauging whether the translator was up to the task as he does not speak Chinese. Neither does national security adviser Jake Sullivan, nor any of Biden’s top China advisers.

This highlights a larger issue in US-China relations – Chinese understanding of the US far exceeds American understanding of China. Part of this is actively induced by China; Chinese civilisation is often portrayed as singular and complex, which may discourage Americans from believing they can understand China or even attempt to.

On the other hand, American students’ interest in studying in China peaked after the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and has been declining since. The coronavirus pandemic and recent bilateral tensions have accelerated this decline.

The waning interest and opportunities for Americans to study Chinese may already be hurting US diplomatic efforts. The American translator at the Alaska meeting reportedly made at least six mistakes, which could have added to the tension.

It would be a great tragedy for American students if the new suspension lasts as long. American students who could have studied in China would turn instead to other countries, exacerbating the dearth of China expertise in the US.

On the flip side of the coin, alarming changes in China, such as crackdowns on Hong Kong, the detention of two Canadians on espionage charges, and a recent altercation between American students and Chinese plain-clothes police officers, might also scare away prospective American students.

A confident China reminds the US it is a force to reckon with

This, too, evokes the dark days of the Cold War, when American journalists and academics were kept out of China for decades. Absent access to sources, absent the ability to speak to their counterparts and report on activities in China from the mainland, journalists and scholars would be hampered in their efforts to educate the American public about what is really happening in China.

This means that as the US and China move towards what analysts are increasingly calling a “new cold war”, the next generation of American policymakers will be even less informed about China. They will be left to increasingly depend on government sources when it comes to China – be it hawkish American rhetoric or bombastic Chinese propaganda.

The old generation of American China scholars are gone, and we have been too slow to replace them.

“In recent years, US policy and political rhetoric towards China have been dominated by officials with limited knowledge of developments in that country,” he wrote in The Washington Post.

“It is not in the United States’ interest to turn the Chinese into enemies. If we want to encourage them to work with us for our common interests, we need some fundamental rethinking of our policies. This in turn requires that high officials be willing to support our friends in China and learn more about its internal dynamics.”

At the time of his death Vogel was reportedly working on a policy paper on US-China relations that he intended to submit to the incoming Biden administration. It remains to be seen whether there is anyone now who will urge the US to reconsider the estrangement its new China strategy is set to exacerbate.

The sobering reality is that the US and China, and their leaders, diplomats and peoples, will need to deal with each other for the foreseeable future, and that both sides would benefit from a greater understanding of each other. China is already ahead in this regard, and the US must act quickly to catch up.

Chi Wang, a former head of the Chinese section of the US Library of Congress, is president of the US-China Policy Foundation