China is replacing the US in a new global order, whether the world likes it or not

Ho Kwon Ping says a new global order, with China as the dominant player in Asia, is coming into force. To every Chinese person with a keen sense of history, Pax Sinica is a legitimate reversion to the golden Han and Tang eras

So – how shall we assess the past year? First the good news: the global economy remains robust, with the US stock market surpassing its historical peak. The not-so-good news is that other capital markets are tanking, and a decade-long period of low interest rates is ending.

The bad news is that the gathering storm clouds of a spreading trade war, an increasing Chinese assertiveness, and the rapidly declining prestige of the US globally, are darkening the geopolitical sky.

But today we can perhaps discern two distinct trends. One is the accelerating but hopefully not-yet-terminal decline of democratic liberalism as the dominant ideology of the post-war global order.

The second is the transition, at least in the Asian region, from Pax Americana to Pax Sinica. And the interaction of these two trends, like tectonic plates grinding inexorably against each other, will determine whether there will be peaceful or cataclysmic geopolitical change for the rest of this century.

Liberal democracy and its major outcome, the globalisation of the movement of both capital and labour, are facing their most serious existential threat since the end of the cold war half a century ago.

The angry dissonance which spewed out from the excesses of financial capitalism and the inequalities of globalisation has not faded. Indeed, it has found stronger organisational vigour with far-right, populist movements and governments in Austria, Italy, Hungary – the list goes on.

Almost unimaginable a year ago, the staunchly centrist or social democratic governments of Germany and Sweden have been besieged by far-right political parties.

Ironically, the continued unravelling of liberal democracy in the past year has shown that the most serious challenge is not external, from either ultra-nationalistic populism in the West or dynamic state capitalism from China. It is from within – the failure of intellectually, morally exhausted liberal democracies to offer a compelling alternative to far-right populism.

Pax Americana and liberal democracy are at a frail, dangerous crossroads; will they somehow find the will to reinvent themselves, or will today’s leaders of liberal democracies be complicit in their own demise?

In the Asia-Pacific region, the single most important trend is the slow but relentless emergence of a Pax Sinica. Most Western views of China have been conditioned by the 20th-century world order, which looks at the world through the lens of a largely American perspective. What is good for the US is good for the rest of the so-called free world.

In large part, America has legitimately and deservedly won this trust. Not only did it lead the Allies in winning the second world war, but in the creation of the subsequent Pax Americana – a polite euphemism for hegemony – the US also guaranteed by political and military might the sovereignty, security, and stability of countries willing to subscribe to its worldview.

This has lasted for some 70 years but will possibly not extend past the next century. Not only because America’s global leadership is being seriously eroded by its own president, but because Chinese policy has taken a more overtly nationalistic turn.

For the past few decades when its ascendancy was still uncertain, China was content to tone down its assertiveness. Chinese leaders preached more coexistence and cooperation than confrontation and competition. No more.

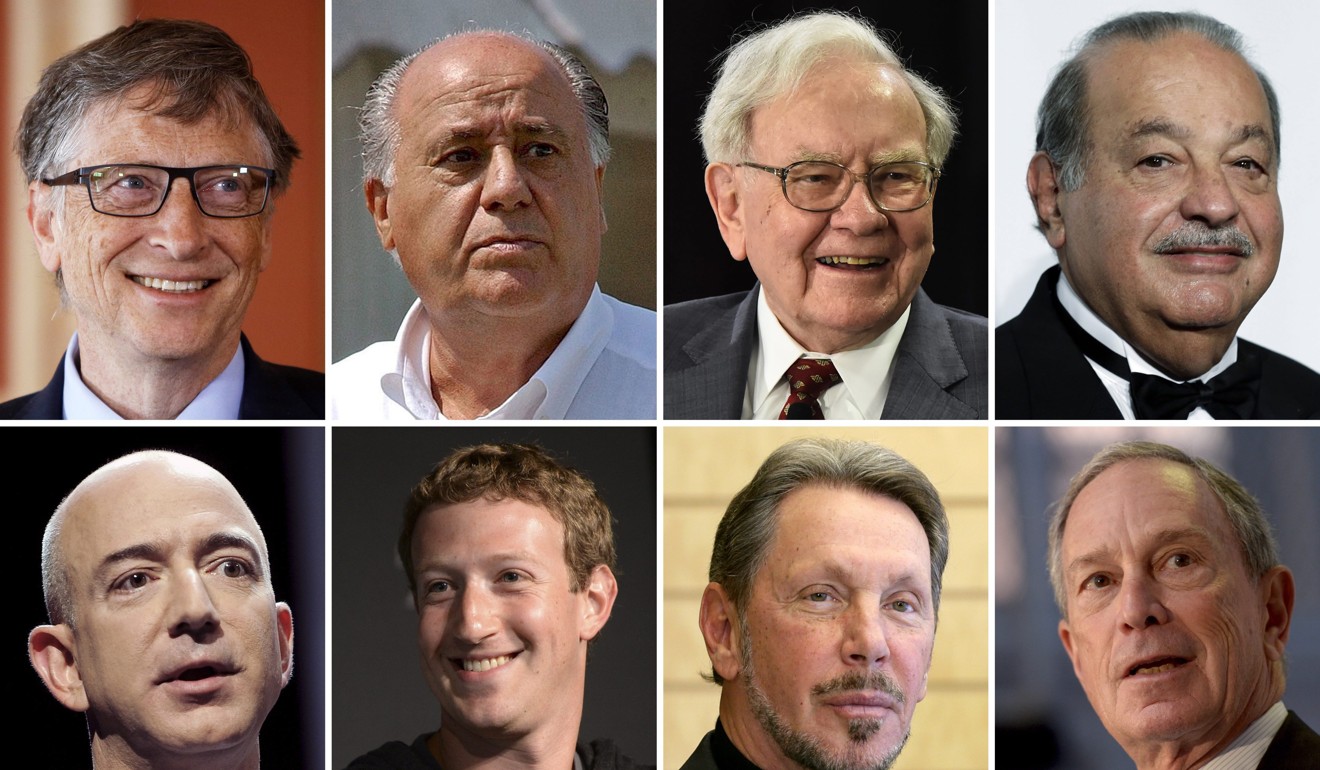

Even conservative estimates project that, within 20 years, the overall Chinese economy will be about one-third larger than the US economy. But because on a per capita basis it will still be less than half that of America’s, there remains a lot of room for the Chinese economy to grow before reaching a developed-world slowdown.

In 1998, Chinese military spending overtook that of Russia. Today, it is more than double that of Russia but still less than that of the US. Reaching military parity may take longer than 20 years, but it is within sight of medium-term strategic planners in both countries.

To advocates of the current world order, where the US is the ultimate global peacekeeper and policeman, Pax Sinica may sound sinister and at best a hidden form of Chinese imperialism.

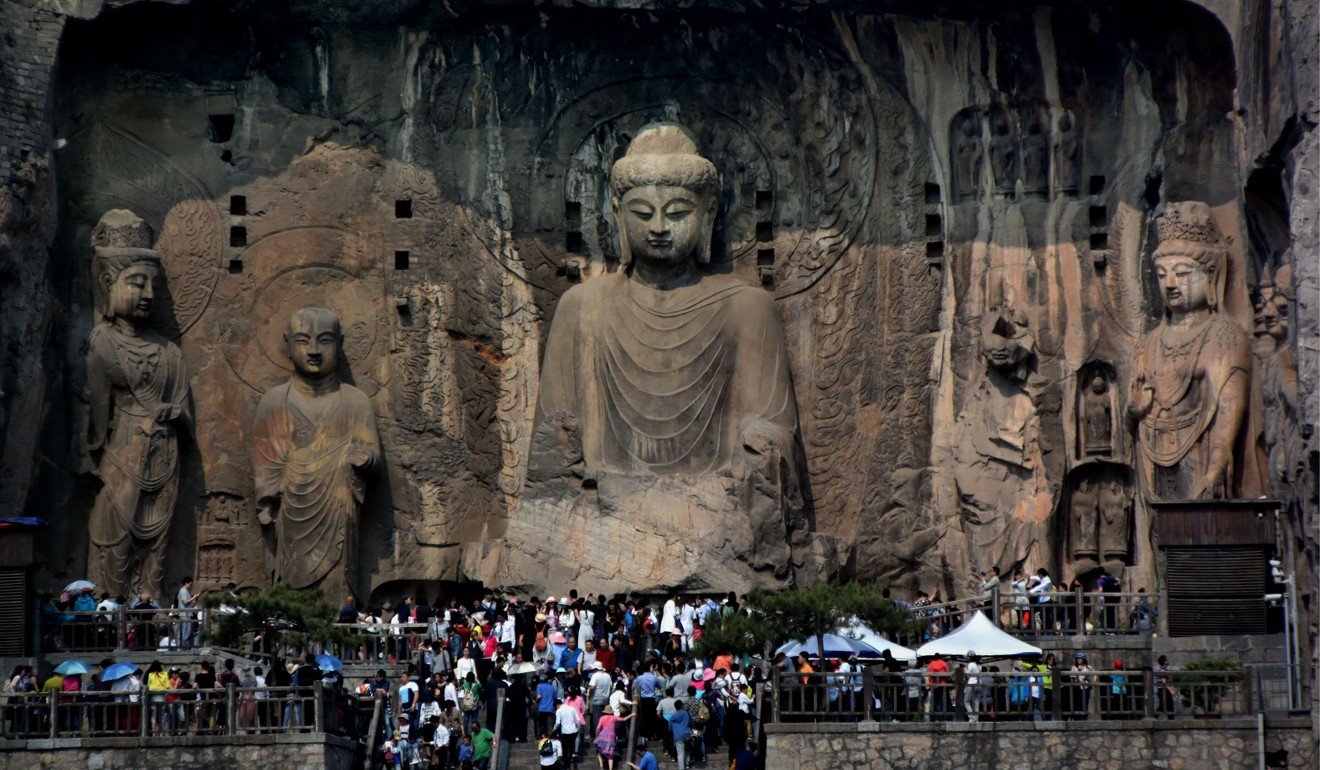

To the Chinese however – and every Chinese person has a keen sense of history – Pax Sinica is a legitimate reversion to its centuries-old, historically validated role – and there have been previous Pax Sinicas during the period of Han China, about 2,000 years ago, or Tang China about 1,000 years ago.

These were in fact the golden eras in Chinese history, when China was an open, cosmopolitan and enlightened civilisation exercising more soft than hard power to become the dominant player in Asia.

The point that a newly assertive China wants to make to the world and particularly its neighbours is a nuanced one.

On one hand, Pax Sinica, even centuries ago, did not have territorial conquest as one of its aspirations. Chinese historians and policymakers frequently allude to the difference between the Chinese concept of a China-centric hegemony and the Western notion of a territorially expansive empire.

On the other hand, China clearly wants to be recognised as the primary power in Asia – the first among equals.

Opponents of a Pax Sinica point out, however, that American pre-dominance in East Asia is at the overt invitation of Japan, South Korea and others.

China’s record as a responsible global player in climate change, financial services or regional infrastructural investments is growing. But, in other areas, it still has to convince sceptics that a Pax Sinica will be at least as benign as Pax Americana. It has to contend with deep-rooted wariness from Japan and Vietnam, and assure the world community the One China policy vis-à-vis Taiwan will be resolved peacefully.

But whether the world likes it or not, whether it will be total or partial, some kind of Pax Sinica is clearly in the offing. A civilisation as old, as continuous, and as resurgent as China has a sense of its destiny, and it’s certainly not what the West has in mind.

Ho Kwon Ping is executive chairman of Banyan Tree Holdings. This is an edited version of a speech he gave at the Singapore Summit on September 15