Why the yuan and other Asian currencies won’t follow the Turkish lira into free fall

Neal Kimberley says while US tariffs may have been the tipping point, Turkey’s currency woes are rooted in weak foundations that other Asian economies do not share

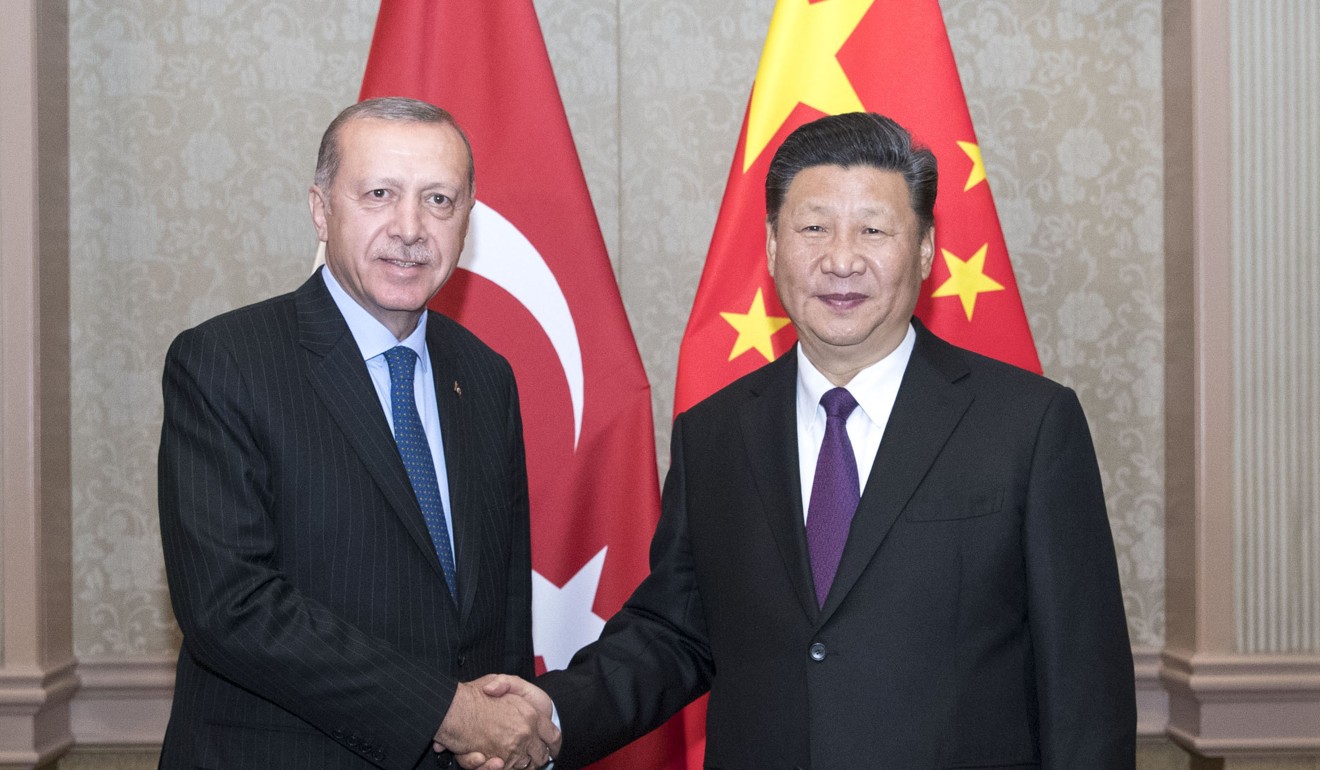

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may have characterised his country’s current situation as an “economic war” and the slide in the value of the Turkish lira has been accentuated by the deterioration in relations between Turkey and the United States, but the currency was arguably already resting on poor foundations.

With Erdogan a self-described “enemy of interest rates”, the Central Bank of Turkey has been slow to tighten monetary policy even though inflation in July was 15.85 per cent year-on-year, more than three times the Turkish central bank’s 5 per cent target.

Additionally, Turkey runs a current account deficit and Turkish non-financial corporations have taken on a mountain of US dollar-denominated debt that has to be serviced. Not only does Turkey need foreign investment inflows to bridge that current account deficit gap, its companies need US dollars to service their debts.

In a nutshell, China is far better placed than Turkey to manage that US dollar debt exposure

Admittedly the same data showed non-bank borrowers in China had US$548 billion of outstanding US dollar debt, but that only represented some 4 per cent of the IMF’s measure of China’s GDP, at US$14 trillion.

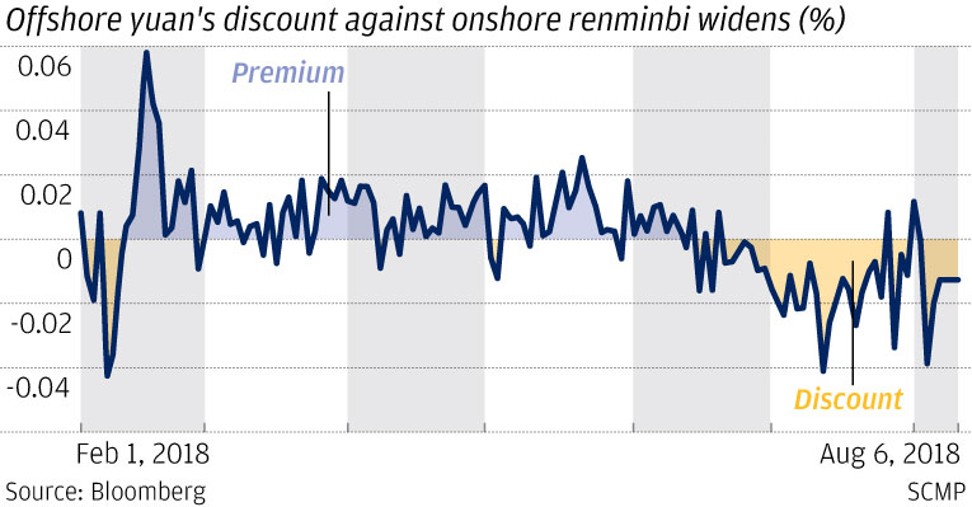

“Going forward, depending on market developments, more counter-cyclical measures may be announced,” HSBC said, while recognising that “the risk of an even weaker [yuan] exists, considering the US’ latest proposal to potentially impose punitive tariffs (be it 10 per cent or 25 per cent) on an additional US$200 billion of imports from China.”

Even if the yuan keeps weakening, investors could rationally conclude that the move would be measured, with the PBOC watchful in the background, rather than prove to be in free fall as has been the case with the Turkish lira.

More broadly, as analysts at Natixis in Hong Kong argued on Friday, emerging Asian economies “are in a strong position to absorb external shocks”, bolstered by “ample foreign exchange reserves to short-term external debt and prudent fiscal and monetary policy to prevent overheating” and having taken “decisive steps to ensure macroeconomic stability”.

The French firm also noted that, in contrast to Turkey’s current account deficit of 6.3 per cent of GDP, most “emerging market Asian countries have current account surpluses” and even the Philippines, Indonesia and India have deficits of less than 2 per cent of GDP.

In the case of the Philippines, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas raised interest rates by 50 basis points to 4 per cent on Thursday, its biggest hike in a decade, and its hawkish tone prompted US bank Goldman Sachs, writing on Friday, to become “more constructive” on the outlook for the peso.

Admittedly, in the same note, the US firm tweaked its forecasts for currencies such as the Taiwan dollar “to be slightly more bearish” but not because of anxiety about a contagion effect from the Turkish lira.

Instead, it was the linkages between China and open economies in Asia that prompted Goldman’s forecast adjustments, given that the US bank sees a risk of some further yuan weakness on a six-month horizon due to the ongoing China-US trade war.

The currencies of China and other economies in the region rest on much sounder foundations than the stricken Turkish lira. Investors shouldn’t automatically assume that, just because Turkey’s currency has collapsed in value, other currencies in Asia will also materially weaken.

Neal Kimberley is a commentator on macroeconomics and financial markets