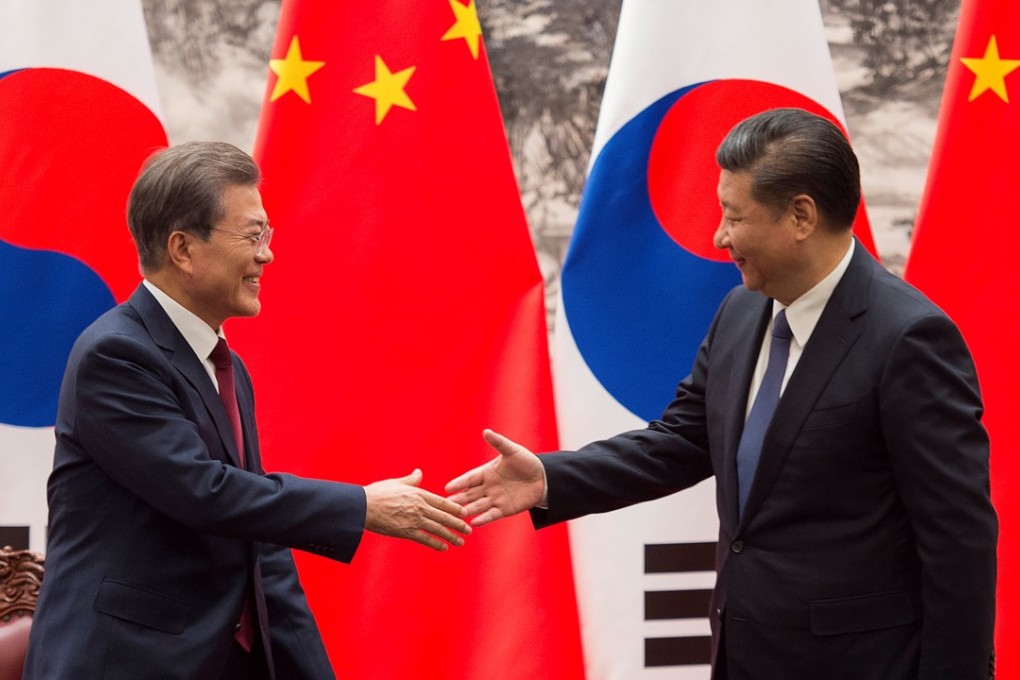

More time and effort needed on Beijing, Seoul relations

Expectations for the summit between Xi Jinping and Moon Jae-in proved too high, and at the end of the day pledges are hollow without concrete commitments

The alleged incursion, played down by Beijing as a routine mission, compounded disappointment about a trip for which expectations should have been low. Officials had made clear that there would be no statement or press conference after the meeting. Much was made by South Korean media that Moon was met on arrival by a low-ranking Chinese official, seen as a snub. Security guards are also claimed to have assaulted photographers accompanying Moon to a trade show, a matter being investigated.

There is a saying among South Koreans that their country is like a shrimp, in danger of being crushed by two whales, a reference to leading economic partner China, and foremost security ally the United States. North Korean nuclear and missile tests aimed at the US and the South prompted deployment of THAAD, but the fallout from the Chinese sanctions have cut economic growth by an estimated 0.4 per cent. There was a sense of relief in October when Seoul and Beijing agreed to mend ties, the impetus being a pledge by the South not to threaten Chinese security interests.

But pledges are hollow without concrete commitments; the lack of progress made by Moon revealed the continuing fragility of relations. Beijing and Seoul have shown a willingness to work together on defusing the North Korean crisis and that will build trust. Mending fences will take time, effort and greater pragmatism.