The diplomat arrived, and stirred the hot latte put before him without enthusiasm. His spirit was low. The Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Netherlands had ruled against his government on the Philippines brief in the South China Sea case. And his job was public diplomacy. For him and other Chinese “public” diplomats, it was not exactly the night before Christmas.

Despite all those Western think tanks, China has proven about as easy to unravel as string theory

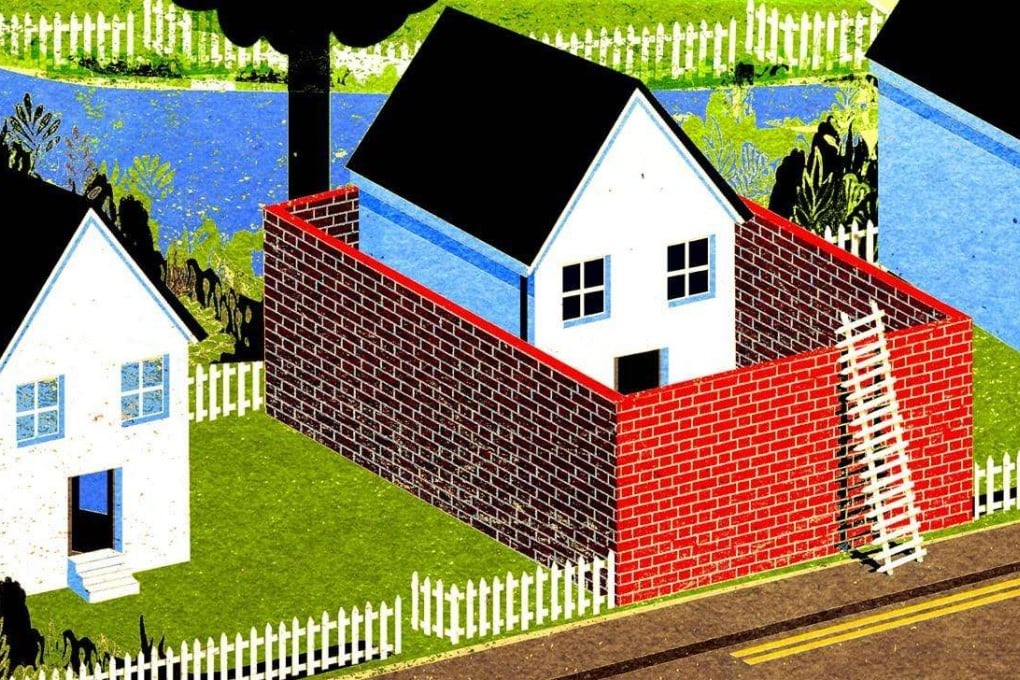

China is a riddled entity of profound vastness – one big Jupiter surrounded by many twirling Asian moons. Despite all the post-Mao openness, all the enforced globalised intimacy and all those Western think tanks, it has proven about as easy to unravel as string theory. I read academic journal articles and trudge through long books by China “experts”, but sometimes wonder if the notion of a “China expert” is often more hope than realisation.

“There is an occupational hazard for anyone who chooses to write about Chinese politics in the second decade of the 21st century,” admits Professor Kerry Brown of King’s College, London, in his dazzlingly detailed new book ,CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping. “We may live in an age of openness and information, but the inner workings of the Chinese political system … remain one of the few bastions of opacity.” More presumptive “experts” should follow Brown’s lead and humbly offer their “expertise” with modesty. Few do.

Nationalism reigns whatever the ideology

With Beijing, Western arrogance grates. Representing a government atop a continuous civilisation that dates back thousands of years, my friend the diplomat parried my questions by seeking to elicit, sincerely, my thoughts on The Hague tribunal’s anti-China decision on the South China Sea. This struck me as a trap, though not plotted: Anything this American might say short of saying that the tribunal was a CIA front might be viewed by him as anti-China.

In his view, Beijing’s problem is that it is misunderstood by the world. Perhaps – but sometimes it is either understood all too well or deliberately misunderstood