Don't compromise Hong Kong's basic principle of equality before the law

Surya Deva says it goes against the Basic Law to deny the lower strata of society a say in political governance. For the sake of the government's legitimacy, the chief executive must build an inclusive society

Since assuming office in July 2012, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying has hardly taken a wrong step in triggering a governance crisis in Hong Kong. Enough has already been said about the biased report to the National People's Congress Standing Committee, which resulted in a highly restrictive and arguably unconstitutional decision on August 31. Then Leung failed to show the required courage and leadership skills to engage democracy protesters at the outset and offer them legitimate concessions to resolve the crisis.

His latest step, giving an interview to the "foreign" media, was perhaps to better reach the so-called "external forces" fuelling the democracy demands in Hong Kong. In the interview, Leung, among other things, said that containing populist pressures was one of the reasons the nominating committee under Article 45 could not give proportional representation to Hongkongers earning less than HK$14,000 per month.

The subsequent clarification posted on the chief executive website that "the design of the Basic Law requires the chief executive to take into account the needs of all sectors with equal importance" does not really help much.

Giving equal importance does not mean according identical treatment to different people. Moreover, why should the lower strata of society be denied any say in political governance in the name of achieving "balanced representation"? Such an outcome is in sharp contrast with the pro-poor image Leung carefully cultivated during his election campaign.

Poor Hongkongers should not be at the welfare mercy of a local government controlled by Beijing and tycoons. The Basic Law does not really contemplate or legitimise this kind of exclusion and continued disempowerment.

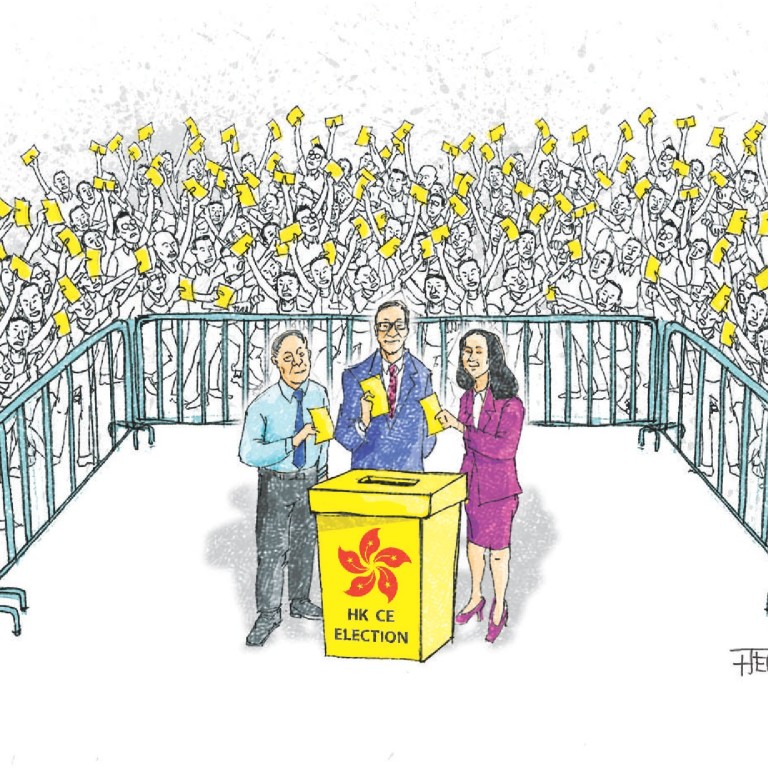

The Standing Committee decided that the requirement for the nominating committee to be "broadly representative" will be satisfied if it is modelled on the current Election Committee. However, it is worth recalling that this committee was modelled on the selection committee for electing the first chief executive.

For historical reasons, even if the 400-member selection committee was regarded as broadly representative in the 1990s for a Hong Kong breaking free from its colonial past, it can by no means be treated as broadly representative for a special administrative region of China in 2017.

The nominating committee must be representative of Hong Kong people rather than merely of various business sectors, professions, occupations and religions. While there need not be an exact numeric representation, it should not be built on an institutionalised exclusionary policy for certain sections of society.

In the current Election Committee, how many people really represent, for example, Hongkongers living below the poverty line, senior citizens, women, the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community, people working in informal sectors, self-employed people, students, homemakers, and people belonging to religious, linguistic and racial minorities?

Excluding certain people from having a say in the political process on economic grounds would be inconsistent with the equality guarantee under the Basic Law as well as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Leaving aside legal arguments, let us also not forget that poor people are poor not merely because of their birth. In most cases, they remain poor because they are denied access to development capital - whether it is a lack of adequate nutrition, health services and housing; limited access to quality education and vocational training, or the availability of finance to start a business.

Rather than rationalising the continued exclusion of the less fortunate sections of Hong Kong society from the mainstream, Leung should have offered them diverse development ladders.

One may argue that democracy is no panacea and that it does not treat poor people any better. There is some truth here, but being denied even an opportunity to compete for public office is much worse than not being able to win the race. If the lower strata of society has no hope for political or economic empowerment, why should they follow laws and believe in the rule of law?

Businesses should not be afraid of a democratic Hong Kong because democracies have safeguards in place to protect the interest of minorities. Nor should we be greatly worried about populism because unsustainable welfare policies are weeded out by increasingly mature voters.

At the same time, tycoons should not take for granted that the law is an instrument to serve only their interests. Nor should they assume that the free market economy implies a total absence of laws and policies aimed at redistributing inequitable accumulation of wealth.

Instead of continuing the colonial legacy of unrepresentative, exclusionary and divisive governance, the chief executive should work towards establishing a more inclusive and representative government. Leung should know by now that much more than his personal reputation as a leader is at stake here.

Democracy or no democracy, Leung and future chief executives have no option but to cultivate the legitimacy of the local government in the eyes of Hongkongers. Doing so will also help Beijing to overcome some of its unfounded fears about Hong Kong.

But this goal of legitimacy is hardly achieved by flying an elite group of tycoons to Beijing to meet the president, while using force against non-elitist democracy protesters.