The logic of Beijing's vision for 2017 chief executive election

Regina Ip says its so-called hard line on Hong Kong's electoral arrangements for 2017 is based on a sound understanding of international law and the provisions of the Basic Law

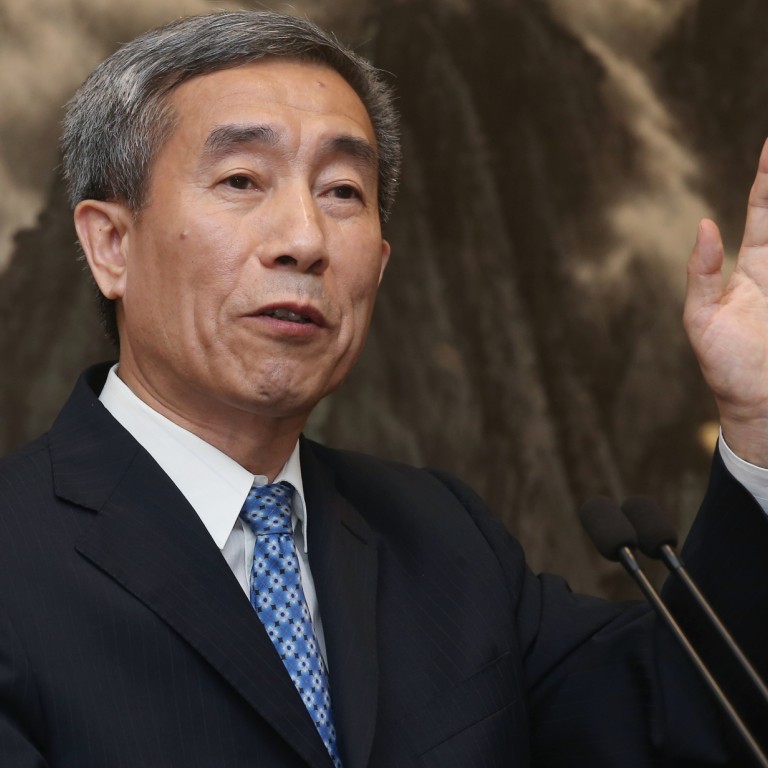

In a further effort to win over the support of Hong Kong people, in particular that of legislators in the pan-democratic camp, Li Fei, deputy secretary general of the National People's Congress Standing Committee, met a cross-section of Hong Kong representatives at three seminars held in Shenzhen this month.

Even before the meeting, some of the democrats, who got wind of the "hard line" to be taken by the central authorities, already despaired of a last-minute, dramatic breakthrough, as had happened in the previous constitutional reform exercise in 2010. What is it about Beijing's vision for the chief executive election by universal suffrage in 2017 that led the pan-democrats to turn pessimistic?

It is not just the asymmetry of power but also the asymmetry of argument that might have led the pan-democrats to become a spent force ahead of the endgame. Whatever you might think of Beijing's "hard line", the arguments put forward by Li, an official clearly schooled in legal theory and logical analysis, deserve close scrutiny.

On the proposition that the chief executive election should be conducted in accordance with "international norms", Li noted that, in accordance with article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a political right is a unique right in that it is one which needs to be conferred and implemented by law. As the covenant was a document entered into by state parties after protracted negotiations, the actual arrangements realising such a right need to be implemented by way of legislation drawn up in the light of the actual circumstances in each jurisdiction.

As a footnote to Li's comment, and a reality check on claims that Hong Kong's electoral arrangement must conform with certain opaque "international standards", it is noteworthy that the covenant was adopted by the United Nations in 1966. Many nations, including the US and Britain, entered reservations in respect of their territories. The UK entered a reservation in respect of Hong Kong people's right to vote, while the US entered a number of exceptions reserving, among others, its right to implement the death penalty.

Second, Li pointed out that while the legal system enacted in accordance with the principles enshrined in article 25 is fair, the outcome cannot be equal as there is only one vacant position where the highest office is concerned. It is for individuals seeking that office to work within the system to achieve their goals. It would not be fair for the system to be constructed in such a way to favour any individual or party.

In April, during Li's meeting with legislators in Shanghai, he made a similar point that the Basic Law was drawn up after a thorough consultative process in Hong Kong 30 years ago, before any of the politicians or political parties now active here started their political life.

The four-sector composition of the Election Committee in the Basic Law represented the outcome of detailed consultation with a wide cross-section of Hong Kong's community. If the nominating committee is to be based on this same model, which represented a decades-old consensus, it would hardly be fair to argue that the system was pitched against today's democrats by design.

Li pointed out that, under article 25, the principles which must be observed are that the right to vote must be universal, equal and held by secret ballot. The expression of "the free will of the people" could only be secured where law - which is enforceable and respected by all - exists.

Li cited, as examples, elections in countries like Iraq or Thailand, where the outcomes were not respected by the voters. Thus, without the rule of law, the people's right to express their will could not be secured.

Finally, Li, who is also chairman of the Basic Law Committee, questioned the assertion - put forward by many to entice the pan-democrats to accept the NPC ruling - that Hong Kong people should pocket whatever arrangement is endorsed by the Standing Committee as "the second or interim best". He considered that whatever arrangements are endorsed by the Standing Committee should be viewed as the "best arrangements for Hong Kong" in light of the actual circumstances at this point in time.

Societies advance in the course of time. When the Athenians decided women, foreigners and slaves should not have the right to vote 2,500 years ago, that was perceived by the authorities then to be the most reasonable arrangement. So was the British decision to deny women the right to vote until 1928.

If the framework endorsed by the Standing Committee manages to secure the requisite support of our legislature, there is no reason to doubt that progress would come, and in a much shorter time span than in ancient Greece or Victorian England.