After June 4, China is still fumbling towards respect for rights of all

Jerome A. Cohen says despite the changes made to China's human rights legislation after June 4, progress has been slow and the plight of those advocating for democracy little improved

We are entitled, 25 years later, to ask about the enduring legacy of June 4. Its immediate impact on China's legal system and civil and political rights was, of course, disastrous. For several years, savage repression decimated a system that, only a decade earlier, had begun its post-Cultural Revolution reconstruction.

The mid-1990s, however, spurred by Deng Xiaoping's 1992 "southern tour" and the Communist Party's effort to attract foreign direct investment, marked a return to the cautious but persistent legal progress of the 1980s. This, despite "strike hard" campaigns and other setbacks, seemed to promise greater protection of human rights, not only in theory but also in practice.

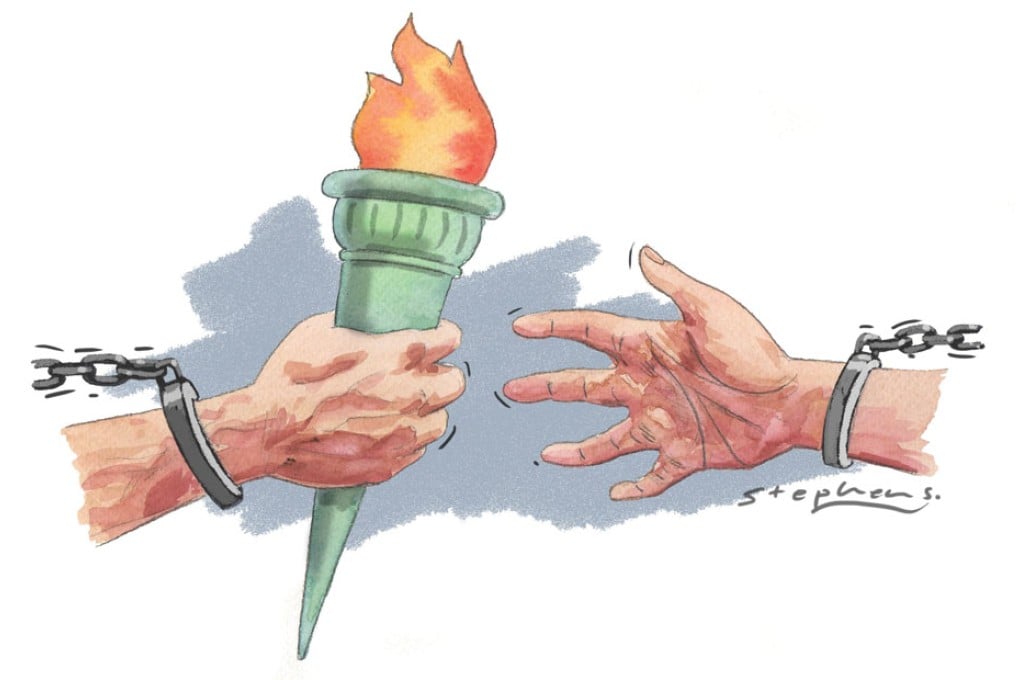

The past 20 years have witnessed a continuation of China's legislative progress. But what has not continued, despite attractive constitutional amendments and generally progressive procedural and substantive laws, is the promise of gradually realising the freedoms of expression, association, assembly, demonstration and religion enshrined in China's constitution. Nor, in practice, has the police-prosecutorial-judicial system over which the Communist Party presides protected the criminal justice and litigation rights of those unfortunate enough to become involved in "sensitive" cases, broadly defined.

Democratic activists and the human rights and public interest lawyers who dare to represent them have been subject to especially disgraceful abuse.

Indeed, in recent years, despite China's impressive economic development, the situation for civil and political rights has significantly deteriorated, and prospects for the immediate future appear grim. The long-time criminal detentions of the distinguished human rights advocate Gao Yu , the able public interest lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and many others are a sobering reminder of reality.

Was this situation avoidable? It is a far cry from the China that my wife, Joan Lebold Cohen, and I experienced when, after a number of visits beginning 1972, we were finally allowed to live in Beijing at the start of 1979. Those were the heady days of Democracy Wall, an exciting period for all, whether Chinese or foreigners, social scientists or visual artists. Speech was really free, and "sit-ins" took place in front of city hall. The Central Academy of Fine Arts invited my wife to give lectures on contemporary American art before hundreds of artists and students who gasped at their first glimpses of slides of Western abstract paintings, in an atmosphere that was electric with questions and comments.

We knew it couldn't last, and it didn't, but this brief transition did introduce a decade of limited progress in many fields. Yet the democratic ferment generated by the 1980s proved hard to contain, as demonstrated by the fall of the reformer, party general secretary Hu Yaobang , in the 1986-87 campaign against "bourgeois liberals", and by the events leading up to the June 4 massacre after Hu's death two years later.