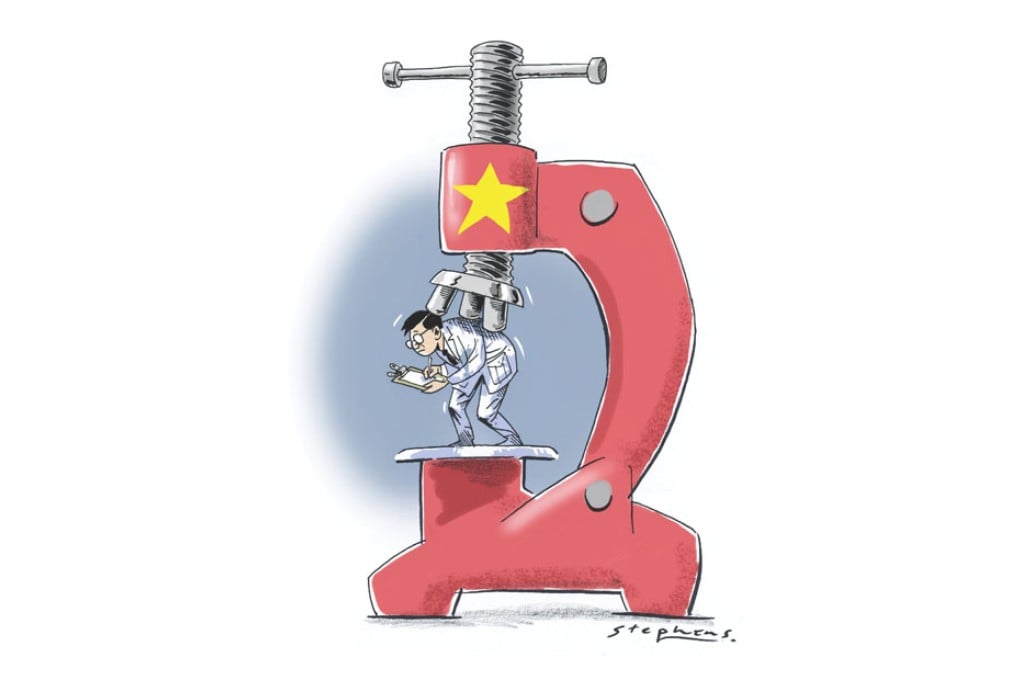

China can't stem brain drain without revamping its research culture

Cong Cao says Beijing's determination to lure back overseas Chinese talent should go beyond financial incentives; it must be matched by a resolve to create a truly open research culture

The threat of a "brain drain" has long lingered over China's ambitions to transform its economy from one reliant on low-cost manufacturing to one powered by home-grown innovation. Alert to the danger, Beijing has acted swiftly to counter the departure of its scientific and entrepreneurial talent overseas.

Back in 2008, the Chinese Communist Party turned headhunter when it launched its "Thousand Talents" scheme to tempt the brightest and best Chinese back to their homeland after periods studying and working abroad.

The policy was designed to attract, in 10 years, through generous salaries, start-up packages, housing and tax incentives, 2,000 established academics and entrepreneurs with overseas PhDs and research experience.

On fleeting inspection, the programme is a raging success. Quotas are overfulfilled: 3,300 returnees have been recruited in less than five years. The initiative has lured some of the best academics back to China. Biochemist Xiaodong Wang, elected to the US National Academy of Sciences at the age of only 41, is a notable catch.

But scratch faintly at the surface and the gaping cracks appear. The real cream of Chinese talent is still hungry for a life overseas. And once they have experienced it, they rarely return.

Statistics released by the US National Science Foundation show that, over the past three decades, Chinese have been the top foreign recipients of doctoral degrees in science and engineering from American universities. Upon receiving their PhDs, nearly all the students indicated their intention to remain in the US - more than 90 per cent have managed to stay.