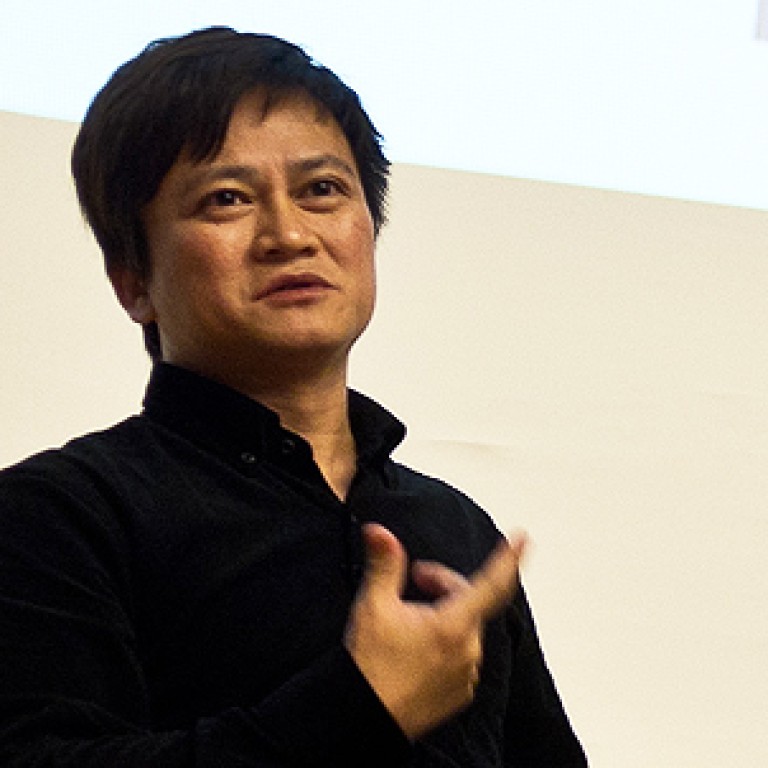

Liberal writer Li Chengpeng on the parallels of football and politics in China

'A game's result, everyone knows it already,' says intellectual

When Li Chengpeng left Chengdu for Hong Kong, a policeman stopped him at the airport. The author expected red tape or harassment, but the policeman was just another fan. He had read Li's books, he said.

The writer, born in the third year of the Cultural Revolution, has become a celebrity gongzhi, or public intellectual, in a very different time. Li's presence is online and the influence of his blog posts reflect the sheer size of the political debate that is taking place online in China.

"I am a patriot, and I love this country, but I have to remind myself not to become a nationalist," he said at the talk. "Football has international rules and no national characteristics, like wearing special shoes. It's not that Chinese players wear fake shoes."

"I have discovered that China's football and China's current society are similar," he said. "A game's result, everyone knows it already. Who is going to appear in the next season, we already know. Who is the enemy, we know that, too."

Li started his activism after joining rescue efforts after the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008. He was among those who fiercely criticised the shoddy construction of school buildings that is alleged to have caused the deaths of thousands of children.

Li became a divisive figure around 2011, when he announced on weibo that he'd run for a seat in China's rubber-stamp parliament, the National People's Congress, as an independent candidate for his Chengdu constituency.

His application to run was ignored, but he shot to fame online for trying. "If you haven't voted for me, I can't represent you" was an online campaign slogan.

Among the people who follow his micro-blog, there are two million staunch supporters, just as many opponents and a million wu mao, internet commentators who are paid 0.5 yuan (HK$0.63) for every derogatory post against government critics, he estimates.

While he insisted that no "special group should be treated like untouchable saints", he chastised the debate among public intellectuals online for "lacking logic".

"When I say we have corruption in China, then people say they have corruption in America too. What does corruption in America have to do with me?" he asked. "But if our prime minister says that we will fight corruption, then these people complain about spitting in public."

His critics' "objective is to preserve this system's illegitimacy", Li said.

But "many people within the system, including some high level officials I have talked to, they know that democracy is a good thing".

"A democracy without freedom of speech as a precondition is a fake democracy. Without that freedom, there is no democracy," he added.

"These issues are sensitive in Hong Kong," he said. "I can speak at ease at mainland universities, but here they affect the 'national image'."

Li said he did not believe that China would experience sudden political reform as in the Soviet Union or in Libya. "Don't be romantic," he said. "The only chance [for change] is that our great nation becomes even stronger."

Strength might give them the confidence "to accept influence from outside", he quipped, drawing laughter and making a point few others could make.