Sino-US relations: a game of defensive play

Lanxin Xiang says China and the US - which have vastly different ideas of political legitimacy - are caught in a strategic framework that prioritises cutting losses over maximising gains

The Chinese saying, "playing music to an ox", describes the phenomenon of two people talking past each other. It's apt imagery for the recently held Sino-US Strategic and Economic Dialogue, which ended as expected, with no serious progress and hardly any improvement in bilateral understanding.

During the 6½ years of the Obama administration, bilateral relations have sunk to their lowest point since the Nixon- Kissinger period of the 1970s. Leaders in Beijing and Washington have not only disagreed about how to solve major problems in the international trading system, global governance and regional security, they have also consistently been talking past each other on the key issue of how to define their relationship.

This is the ultimate result of failing to overcome their fundamental difference about what constitutes legitimacy for a nation state. For Washington, legitimacy has only one element - the democratic procedure, which it considers a universal model applicable everywhere. For Beijing, no political system is universally valid, and the claim that decision-making procedures alone determine political legitimacy is a myth. On this issue, Washington seems to have occupied the moral high ground.

Similarly, whereas Washington claims its intense military and diplomatic alliance-building activities in the Asia-Pacific are "rebalancing" for the sake of regional stability, Beijing clearly sees it as a containment strategy. But more worrisome is the fact that the two leaders use quite different reference points to describe their bilateral ties: President Xi Jinping speaks of a "new type of major power relations", while President Barack Obama insists on a "new model" of relations.

In his opening speech at the dialogue, held in Beijing this month, Xi emphasised that this relationship has no historical precedent or ready-made model as guidance. Obama's opening statement at the dialogue implied, however, that his "model" is based on the idea that he would never compromise on the question of democratic legitimacy, but is willing to build a working relationship with China contingent upon what the US considers proper Chinese behaviour.

China's behaviour will be judged according to what Washington holds as the universal standard. Thus, Obama the lawyer deliberately stresses the term "model", which implies an example to follow or imitate.

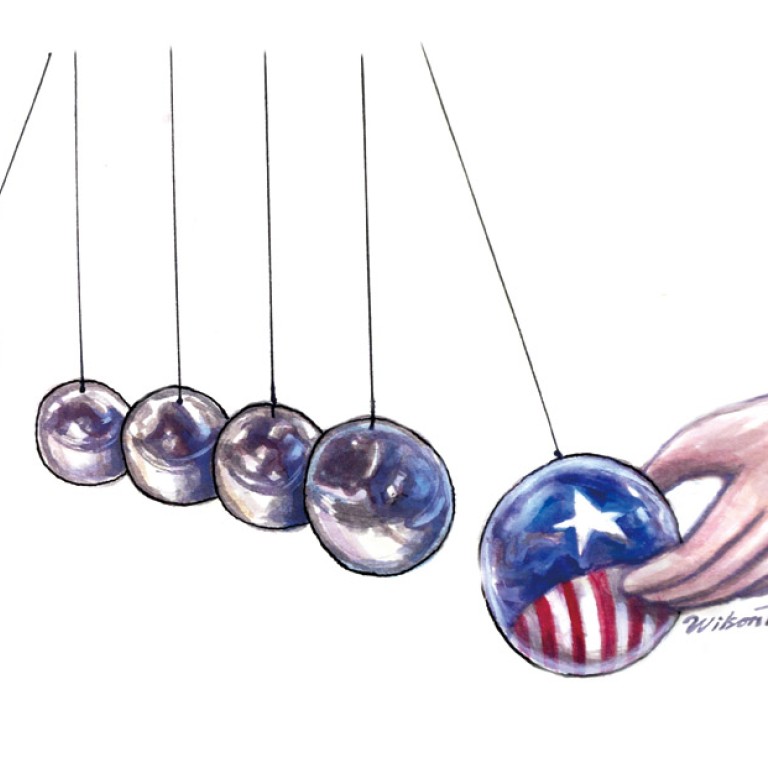

Why do Beijing and Washington keep talking past each other? One plausible explanation is found in the Nobel Prize-winning "prospect theory" of behavioural economics, which posits that people are willing to take greater risks to avoid losses than they are to achieve gains. Instead of making decisions that maximise their overall expected gains, people tend to focus on a particular reference point and give more weight to losses than comparable gains.

That is to say, leaders usually exhibit a status-quo bias. For example, a superpower in decline often considers preventive war a good instrument to forestall the loss of its status and prestige, and is willing to double its effort in existing conflicts rather than withdrawing from them.

Thus, Washington considers Beijing willing to gamble either to enhance its influence at the expense of US interests in diplomatic negotiations, or to offset American influence with an aggressive agenda for territorial gains. With this mentality, Obama's original reference point was the status quo before the eruption of the territorial disputes over islands in the East and South China seas, when Washington had a pliable ally in Tokyo, willing to turn over the responsibility of national defence to the US-led alliance arrangement.

But after Japan suddenly changed the status quo in 2012 to "nationalise" the Diaoyus/Senkakus, the Obama administration began to see this as a strategic advantage for the US in the Asia-Pacific, and decided to abandon a neutral position and "renormalise" its reference point through open support of the Japanese move in the name of alliance solidarity. Therefore, it is not surprising that Beijing sees this American attitude as a major policy reversal.

On the other hand, Beijing also seems to have changed its posture and is willing to take more risks to compensate for losses in diplomacy in its immediate neighbourhood, despite the fact that its crowning foreign-policy objective is to maintain a peaceful international environment as long as possible. The proposal to establish a new type of major power relationship with Washington is aimed at avoiding a downward spiral of strategic relations and preventing what Henry Kissinger called "Anglo-German alienation" before the first world war.

Here, prospect theory can go further in explaining Beijing's assertive behaviour, which is alarming its neighbours, because its mentality, very much like that of Washington, may not be focused on maximising gains but cutting losses.

Thus, we are witnessing a classic security dilemma which has the potential to become a permanent state of confrontation. Taking current US-China relations as a normal state of affairs is self-deluding.

To understand the present crisis, we must recognise that people renormalise their reference point after making gains much faster than they do after incurring losses. In other words, if an international situation turns to the advantage of one state over another, the one who gains will change its reference point to the "new normal" and resist efforts by the loser to revert to the earlier reference point. Call it a new cold war if you will.

It must be pointed out that, so far, American leaders have "renormalised" their reference point much faster than their Chinese counterparts; the latter are on the defensive and ill-prepared for an effective regional policy. In comparison, the US "pivot" to Asia is well designed for re-establishing American influence in the region.

In sharp contrast, the reference point of Chinese leaders continues to be the pre-pivot status quo, as they seek to recover their lost influence. As a result, the US is focusing on rolling back Chinese "aggressiveness" in the western Pacific, while China believes that assertiveness works better to deter the US.

If US and Chinese leaders continue bringing totally contradictory perspectives to the negotiation table, as the prospect theory would predict, it is hard to envision a diplomatic resolution to any crisis in the region that would satisfy both sides.