Why analysts pick on BYD

Warren Buffett has a 10 per cent stake in the company, its shares are flying, its green energy technologies are attracting big government subsidies, and yet analysts constantly complain that BYD is 'too rich'

BYD is a curiosity. The firm gets few breaks in brokerage reports: of the analysts who track the company, 15 have "sell" ratings, six are "neutral", while two are a "buy". Meanwhile, the firm's share price is up by a third in the year to date.

Let's begin with what BYD is. The Shenzhen-based firm makes rechargeable batteries, mobile phone components and solar panels. It is best known as a manufacturer of electric cars and buses, and it broadly identifies itself as a green energy firm.

In 2010 the firm launched the e6, a plug-in electric car that is already part of Shenzhen's taxi fleet. After a 10-month delay, a fleet of 45 BYD electric taxis is scheduled to roll out in Hong Kong on Wednesday. The company, in other words, is a growth stock for the next stage of the development of the mainland economy, which will be more technology-based and more value-added, and one that will help address the mainland's epic pollution problems.

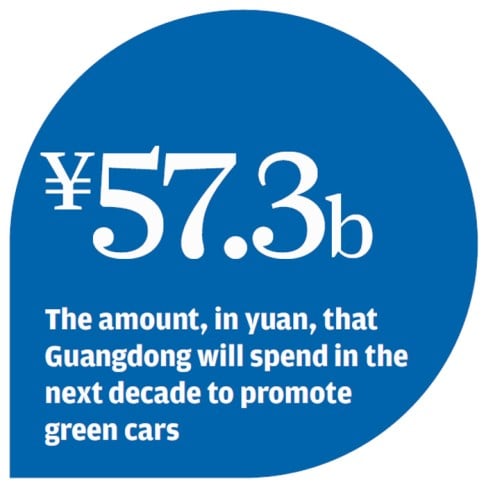

New energy technology is also an irresistible target for policymakers looking to hand out subsidies. The Guangdong government plans to spend 57.3 billion yuan (HK$70.82 billion) over the next decade to encourage the production of new-energy vehicles, and BYD is a consistent beneficiary of such aid.

Nomura analyst Leping Huang says the central government is looking to increase an electric-vehicle subsidy programme, to introduce 500,000 pollution-free vehicles by 2015.

The company is also internationally focused. It is building a plant to make electric buses in California, and it has sold or test-launched electric vehicles in Colombia, Laos, Thailand, Uruguay, the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Britain, and so on. Its international focus seems to bring with the firm international standards in terms of governance.

Nomura's Huang, who has an excellent record predicting the BYD share price, issued a "buy" rating on BYD in a January 8 report, arguing that investors were not fully appreciating the turnaround in earnings that is under way at the firm.

In early April, Huang reiterated his recommendation, citing among other evidence, a global road show by BYD's chairman, Wang Chuanfu, to promote the firm to investors.

The chairman's message of a company poised for a "second takeoff" appeared to have substance, Huang wrote, saying he had observed signs of change at the operational level that included the improving quality of new vehicle models.

Meanwhile, first-quarter earnings showed dramatic improvement, registering a threefold rise over the previous year. Total vehicle sales were up by a quarter year on year.

Some of the gains were driven by the popularity of the Surui compact car, unveiled in September. At a starting price of 65,900 yuan, it comes with self-driving technology.

Huang says a new gas-electric hybrid car, the Qin, as well as a traditional gas-powered sport-utility vehicle, the S7, could help shift car sales into high gear in the second quarter.

So what, exactly, is analysts' problem with BYD?

Most brokerages simply say the firm is too expensive. "We are not comfortable with [BYD's] rich valuation," a report from Bank of America Merrill Lynch said. "The current expectation and valuation are still unwarranted," says UBS. "Valuation still rich," says Deutsche Bank, and so on.

Indeed, BYD trades at an astronomical 52 times expected 2013 earnings. Its carmaking peers, such as Geely Automotive and Dongfeng Motor, trade at just eight to 10 times their expected earnings.

BYD also has a history of disappointing investors. For its 2012 results, released in March, the company declared a 4.4 per cent drop in revenue and a 94 per cent fall in profit.

Concerns over the company's health were in focus last summer after a disappointing first-half earnings result. BYD's vehicle sales for the six-month period were down 9 per cent amid general sluggishness linked to the expiry of a government subsidy on the purchase of fuel-efficient vehicles and moves by some Chinese cities to cap the number of new vehicles.

Meanwhile its smartphone components business suffered setbacks. BYD makes components for Nokia and HTC, not the best clients to have, perhaps, in an era when Apple and Samsung dominate smartphones. Even its solar panel division reported an operating loss for the half-year period, amid weaker prices for solar cells.

Macquarie analyst Janet Lewis says the company received a 550 million yuan government subsidy in 2012, equivalent to 190 per cent of pre-tax profit. She described the full-year result as "saved by government grants", saying the subsidy allowed the firm to avoid a loss in 2012.

The BYD share price is wildly volatile, which is typical for a firm that is long on concept and short on performance. The stock climbed elevenfold in the eleven months after Buffett took a stake in the firm. BYD then fell back close to Buffett's purchase price in 2011, though these days the shares are gaining strongly again. Even Huang, one of the handful of BYD supporters, acknowledges the firm has a history of failing to deliver on promises.

Lewis wonders about the health of BYD's balance sheet, saying she was watching for signs of unmanageable debt, particularly in the automotive business.

Bloomberg reported in March that the firm wanted to raise up to US$500 million through a rights issue. These are unpopular with investors, are hard on the share price, and are typically only done by firms in acute need for capital.

But it is often the case that analysts are most sceptical on a company's prospects just before a major turnaround. Huang says few of his analyst colleagues have taken account of all the hard work that had gone on at BYD during the past three years to improve operations. If those improvements prove real enough, BYD could be well placed for the gradual rise of greener China.