China faces tidal wave of exits by ageing tycoons. Their succession plans will shape China’s future

- Huge leadership change coming for private companies, but many hard-charging offspring are looking beyond the family business

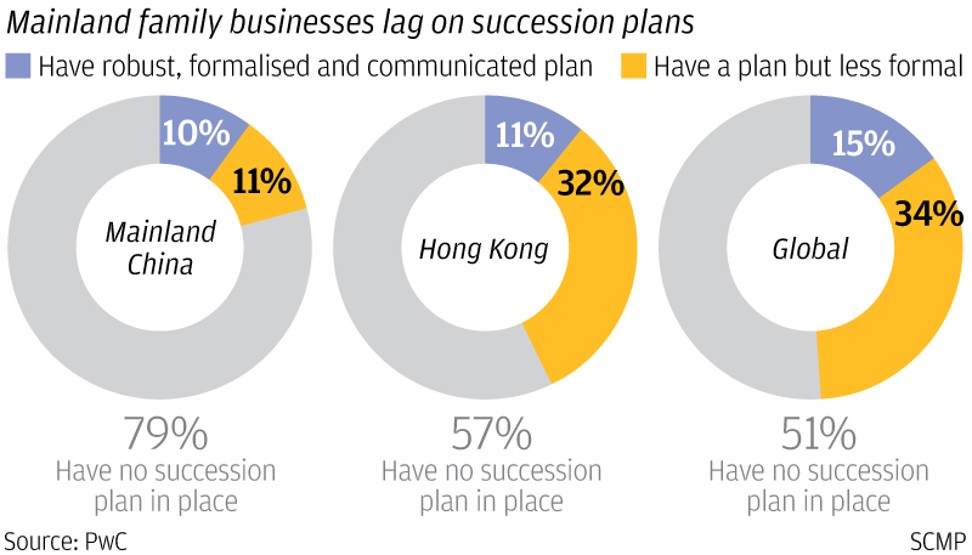

- Chinese tycoons less likely to have handover plans in place than global peers

China is getting ready to be hit by a wave of retirements of ageing business titans who built the private companies that fuelled the country’s economic boom and created its middle class.

These companies are nearly all family owned, headed mostly by men who forged empires largely in real estate and manufacturing since China began experimenting with capitalism 40 years ago.

The changes at the top will hugely impact China’s future, as it speeds up its shift from manufacturing to technological innovation in sectors like e-commerce and artificial intelligence.

But what might seem an obvious succession plan – ageing parent handing over control to groomed adult child – isn’t turning out to always be the rule.

Some scions – many educated in the West – want to prove themselves by creating their own businesses or seizing other opportunities. Some of them are happy to have non-family professional managers brought in to run the core family firm. Meanwhile, others in the second generation are working within their families to diversify the original business by adding in more tech-savvy offshoots, creating what one analyst calls “the business family” to replace the family business.

“Succession in private businesses is crucial to China’s economic health and stability,” said Song Qinghui, chief economist for Shenzhen-based Qinghui Research.

“Private entrepreneurs have played a key role in the leap forward development of the Chinese economy in the past 40 years. They have also accumulated a massive amount of wealth,” he said. “The quality and success of the succession could decide the future of the Chinese economy over the next few decades.”

China’s captains of industry are no longer spring chickens, reflecting an ageing demographic overall in China: One chairman out of every three among the 2,000 non-government owned companies in mainland China’s stock markets is older than 55, while 15 per cent of them are older than 60, according to data by Shanghai Wind Information.

Yet few of them have figured out what comes next.

Of surveyed mainland family businesses, only 21 per cent have a succession plan in place, 28 percentage points lower than the global average, according to a November study by PwC.

“The biggest challenge today is how to embrace the next generation to bring them back to the family fold,” said Roger King, founding director of Tanoto Centre for Asian Family Business and Entrepreneurship Studies at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

“China is moving very rapidly in terms of technology. And I think young people are more and more moving towards technology-oriented businesses,” he added.

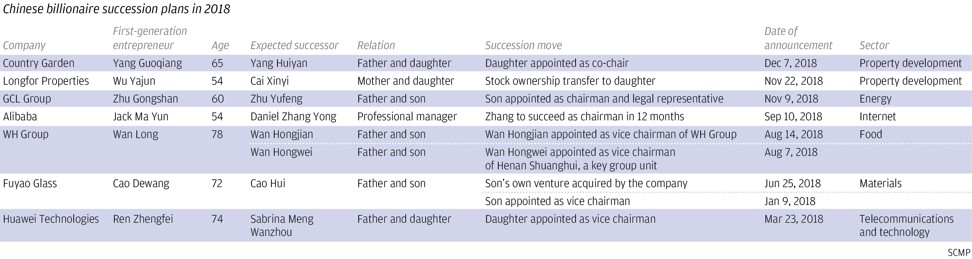

Notably, a larger than usual number of high-profile entrepreneurs made eye-catching succession moves or actually transferred power in 2018.

At least seven billionaires did so – Alibaba’s co-founder and executive chairman Jack Ma, Huawei’s founder and president Ren Zhengfei, Country Garden’s founder and chairman Yang Guoqiang, Longfor Properties’ co-founder and chairwoman Wu Yajun, GCL Power’s chairman Zhu Gongshan, Fuyao Glass’ founder and chairman Cao Dewang, and WH Group’s chairman and CEO Wan Long. (Alibaba is the parent company of the South China Morning Post.)

Their average age is 65, and the sectors span from tech, property and energy, to consumer and industrials.

Six of the seven entrepreneurs have either announced they will pass on corporate ownership or management to their children or taken steps suggesting they will. Ma, on the other hand, will hand over the keys to a non-family member.

But last year’s headline examples – with nearly all passing the baton to adult children – are not what a recent survey predicts is ahead for China’s business elite families.

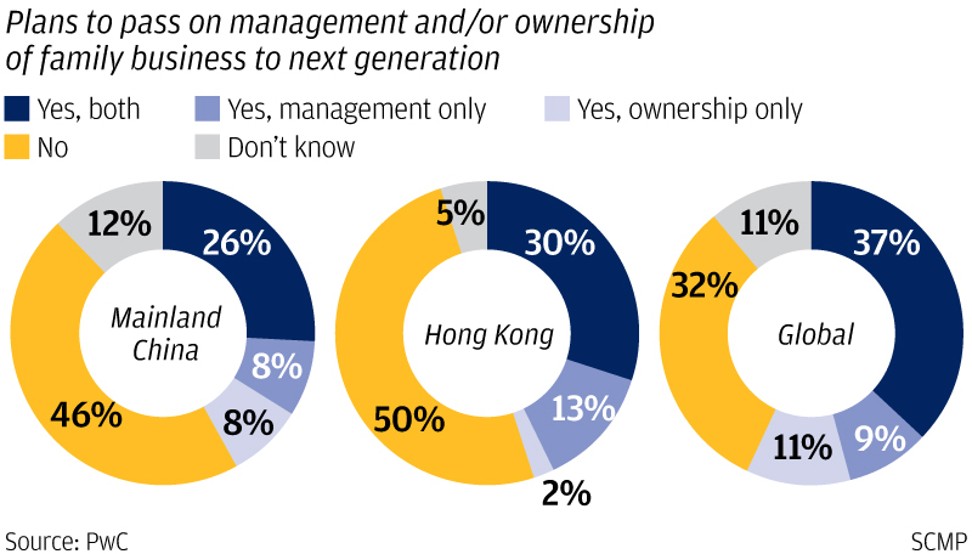

Fewer Chinese entrepreneurs plan to pass on company leadership or ownership to a next generation family member compared to their global peers, a survey by PwC in November found. Only 42 per cent said they will, versus a global average of 57 per cent.

Part of the reason is that the second generation sees the companies they stand to inherit as low value-added and less sophisticated than other ventures they could undertake in industries like banking, investment and technology, the survey said. Some are charging ahead to be the movers and shakers in the new economy, upending established sectors.

Consider Liu Qing, also known as Jean Liu, the daughter of Liu Chuanzhi, who founded Lenovo, one of the largest personal computer makers in the world. Rather than going into her now-retired father’s business, Liu Qing worked for Goldman Sachs in 2002 after obtaining a master’s degree in computer science from Harvard University and joined ride-hailing startup Didi Chuxing in 2014 as chief operating officer.

She was promoted to president of Didi Chuxing in 2015 and helped develop the firm into China’s dominant ride-hailing giant and one of the world’s most valuable startups, with a valuation of between US$50 billion to US$52 billion. That is higher than Lenovo Group and Legend Holdings’ combined market cap of HK$111 billion (US$14 billion). Legend Holdings is the controlling shareholder of Lenovo Group with interests in finance, real estate and technology.

Didi and Legend Holdings also compete in China’s car rental business, as Legend Holdings backs Car Inc., one of the country’s largest car rental firms.

Another challenge for rich Chinese families is how to navigate their businesses in the current technological revolution era – the so-called Industrial Revolution 4.0 – where a fusion of technologies is blurring the lines between physical, digital and biological spheres.

This profound change is ripping through China, with hugely disruptive technologies leading China’s effort to transition from a manufacturing-driven economy to a services and consumer-oriented one.

“Business models that worked well a few years back may no longer function nowadays with the [technological] disruptors in place, and this is no exception to mainland family businesses,” said Jeremy Cheng, centre manager at the Tanoto Centre for Asian Family Business and Entrepreneurship.

“Instead of thinking of passing on the baton to the next generation, families should think about leveraging off talents of the next generation to create new ventures – within or outside of the family umbrella,” Cheng said.

Some Chinese entrepreneurs have started doing this.

Cao Dewang, the 72-year-old founder and chairman of Fuyao Glass, one of the largest auto glass producers in the world, said in June the group will spend 224 million yuan to buy the company that his son Cao Hui founded, paving the way for the latter to succeed as the group’s chairman in the future.

Cao Hui had served as the group’s general manager for nine years, but resigned in 2015 to create his own venture and then developed it into an independent supplier of Fuyao Glass.

Another unique challenge for the Chinese family business is that succession is often coinciding with the company going through a transformation and industry upgrading, said Song from Qinghui Research.

“Most Chinese family businesses are manufacturing firms and have limited growth space in the future. After the next generation takes over, they face the challenge of how to sustain the development and diversify the business,” Song said.

Currently, there are two succession models in China’s family businesses, Song said.

One lets the next generation family members inherit the business, with the assistance of the entrepreneurs themselves or professional managers. The other involves hiring outside managers and having them take control.

“There is no best model. Only which one is more suitable case by case,” Song said. “[But] I think the first one may suit China’s conditions better.”

In addition to Ma, notable examples of tycoons picking outsider managers to take on their business empires rather than family include Lenovo Group’s Liu Chuanzhi and Midea Group’s He Xiangjian.

“Ma is a pioneer among the Chinese entrepreneurs who are still exploring for the best model to hand over their successes to the next generation,” said Joseph P.H. Fan, co-director of the Institute of Economic and Finance at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, in an interview in September when Alibaba announced the succession planning.

Song said most outside managers don’t last long in family businesses because they are less trusted than family.

“Loyalty is a key value that Chinese entrepreneurs attach much importance to. For one thing, it’s usually hard for outside managers to comprehend and be loyal to a family business. For the other, deep from the heart, the family leader doesn’t trust outsiders.”

Zhu Xinli, founder of China’s largest privately owned juice producer Huiyuan Juice Group, hired an outside manager in 2013 to succeed him as the new chairman and president. But one year later, the manager resigned, Zhu returned, and the board appointed his daughter Zhu Shengqin as a member as a step for taking over the business.

Zhou Xiaoguang, who founded costume jewellery manufacturer NeoGlory Group, also tried having three outside general managers run the company, before finally having her son Yu Jiangbo take it over in 2011.

“I’m more optimistic about the model in which professional managers play a role of transitional ‘regents’ and help the new and young ‘ruler’ take control, before they fade out eventually. It will make the succession process more smooth, ” Song said.

A classic case study may be the New Hope Group.

Liu Yonghao, founder of the country’s biggest animal feed producer, passed on the chairmanship to his daughter Liu Chang in 2013, while hiring a corporate strategist as a transitional CEO and co-chair to assist her governing New Hope for three years.

Cheng said a future trend of China’s family business might be to transition from family businesses to business families.

“Unlike a family business, a business family will always own one or more businesses, which may not be the same ones over time,” he said.

“In terms of the nature of succession, a family business will call for picking the best candidate to run the show,” he added. “[But] from the business family perspective, it will be for future generations to adopt and preserve the family’s value system and entrepreneurial spirit in pursuing existing and new opportunities.”