Xiaomi bickering exposes Hong Kong stock exchange’s rivalry with Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses

The world’s fourth-largest smartphone maker is at the centre of a war of words between the Hong Kong stock exchange and the operators of the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses.

Charles Li Xiaojia had to endure a hastily arranged flight to Beijing on Monday night, after a weekend of an uncharacteristically acrimonious war of words between the Hong Kong stock exchange and the operators of the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses.

At the centre of the bickering sits Xiaomi, the world’s fourth-largest smartphone maker and, as of a week earlier, Li’s biggest customer this year in initial public offering (IPO) on the Hong Kong stock exchange.

At issue is whether Xiaomi’s Hong Kong-listed shares can be bought or sold by mainland Chinese investors via the Stock Connect programme, a cross-boundary investment channel between the city and the exchanges of Shanghai and Shenzhen.

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX), of which Li is the chief executive, expected it to be a matter of routine formality that would take effect on July 23. Both Xiaomi and the market operator said so during the company’s debut on July 9.

In a surprise statement last Saturday, the two mainland bourses pulled the rug from under Xiaomi and said the stock would be excluded from the Stock Connect pool, which cuts potentially billions of yuan of capital for the shares, and denies Chinese investors the chance to partake in the earnings of a company that has promised to increase its earnings tenfold.

The about face also caught Hong Kong’s chief executive by surprise, according to several sources familiar with the matter. Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor and Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po assembled a Saturday meeting with HKEX officials after learning of the mainland bourses’ announcement, they said.

The unexpected turn of events weighed on Xiaomi’s stock on Monday, causing it to tumble by almost 10 per cent in early trading before it clawed its way back to close the day with a 1 per cent loss. Still, the episode underscored the politics and rivalry at play between three of Asia’s largest financial markets.

The first consideration was timing. China’s stock exchanges are in bear market territory, with Shanghai’s benchmark index plunging 23 per cent since January, while the Shenzhen gauge plunged by 22 per cent over the same period.

Institutional funds and brokers were concerned that capital would take flight if mainland investors were allowed the opening to buy offshore assets, a Shanghai Stock Exchange official said on condition of anonymity, citing a recent survey. That would undo the crackdown on capital flight that China’s financial regulators and central bank had been at pains to enforce since 2016 and 2017.

“Billions of yuan would flow to Xiaomi if mainland Chinese investors weren’t barred from accessing it,” which would further dampen the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets, said Ivan Li, a hedge fund manager at Loyal Wealth Management in Shanghai . “Xiaomi is a good buy for mainland China’s institutional and retail investors,” which would almost certainly mean capital will flow out to this stock, he said.

A second consideration was rivalry between the exchanges of Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen to be the preferred fundraising destination for China’s technology companies.

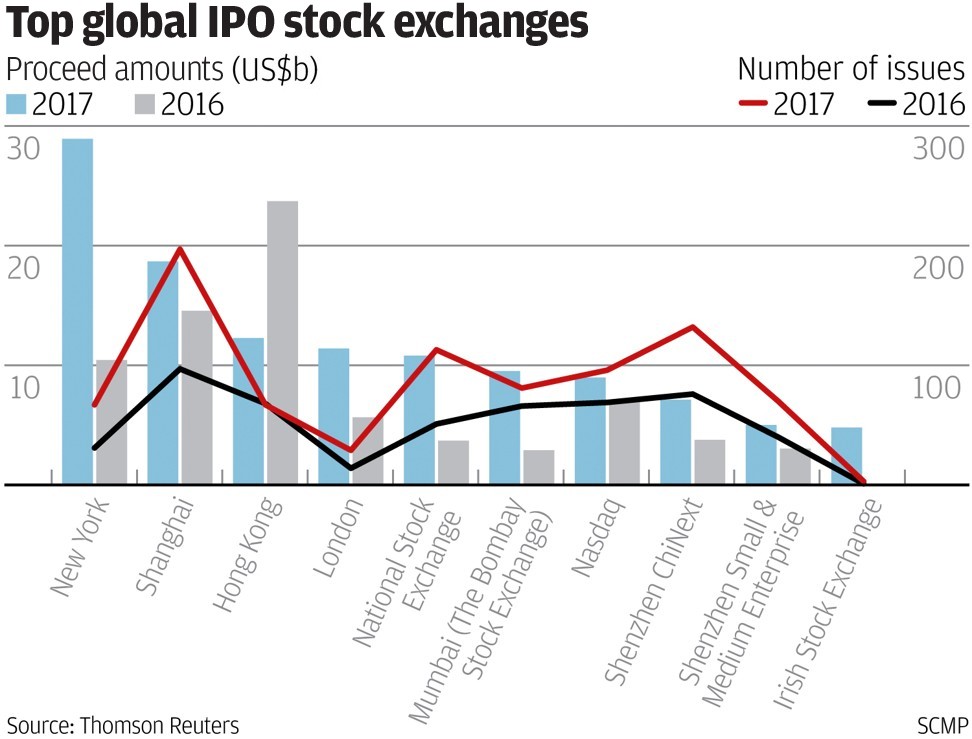

Hong Kong lost the 2017 global IPO race to New York, and was overtaken by Shanghai for the first time at second place. That compelled the HKEX - itself a publicly traded company, while 44 per cent of Li’s HK$45 million (US$5.7 million) annual remuneration package last year comprised share options of HKEX - and the city’s securities regulator to push through the biggest overhaul of listing regulations in three decades to encourage tech start-ups and biotech companies to list.

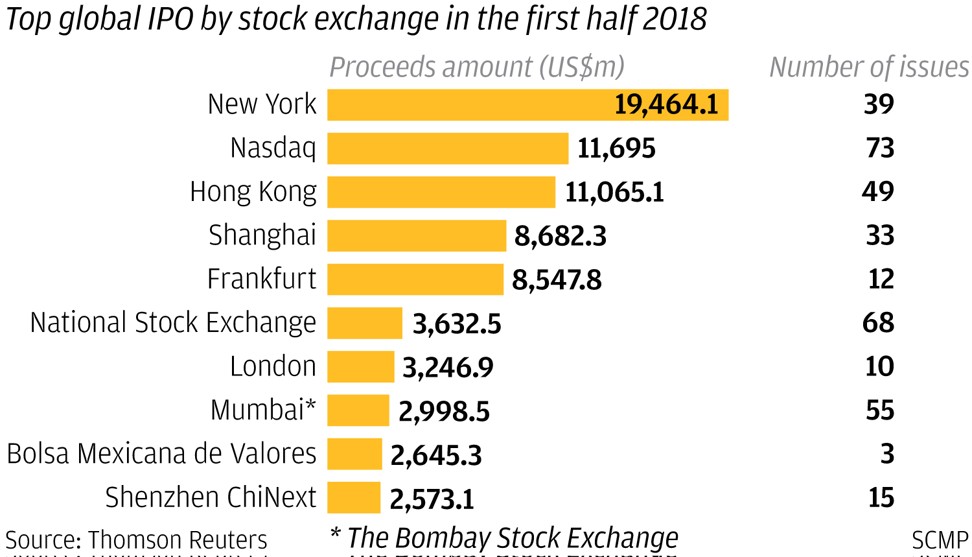

Hong Kong received IPO applications from 98 companies in the first half of 2018, although the proceeds raised were only a third of the estimated US$18.6 billion raised in New York, according to EY’s data. But the city has secured a strong pipeline of potential listings, which could catapult Hong Kong back to number one, EY said.

By comparison, Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses saw 60 IPOs in the first half, raising a combined US$13.5 billion, according to Bloomberg’s data.

In a tilt to economic nationalism, Chinese regulators were pushing for the country’s home-grown tech giants to issue depository receipts (CDRs) for local investors to partake in their growth.

“If local investors were allowed to buy dual-class stocks like Xiaomi, the appeal of CDRs would be diminished, and the CDR plan would be significantly undermined,” said Wu Kan, a fund manager at Shanshan Finance in Shanghai.

Xiaomi was the first company to list in Hong Kong with a weighted voting right (WVR) structure, or multiple classes of shares whereby the founders exerted outsize control even with minority ownership. Liu Shiyu, chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission(CSRC) had personally appealed to Xiaomi’s founder Lei Jun to be the test case in China’s CDRs. That plan was shelved last month before Xiaomi’s Hong Kong debut.

The intention for the block could be “to save the ammunition” for the mainland to help with liquidity in the stock market, and also avoid having too many good-quality tech firms listing in Hong Kong, said Kevin Leung, executive director of investment strategy at Haitong International Securities.

“It also shows different regulatory stances on dual-class shareholding companies like Xiaomi by the mainland and Hong Kong,” he said.

In its discussions with mainland regulators and market operators, the HKEX had urged them to raise the issue if they were not amenable to allow WVR stock to be traded via the Stock Connect, Li said in a statement on Monday. But mainland regulators did not voice their opposition until Xiaomi’s debut, and a week before the stock was officially included in the Connect programme.

Launched first in 2014, the Stock Connect scheme was introduced to allow international and mainland investors to trade securities in each other’s markets. More than 2,000 equities in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong - including HSBC and Tencent Holdings - are now included in the scheme.

Turnover under the Stock Connect scheme for Hong Kong shares has been growing steadily ever since, which now accounts for around 7 per cent of the Hong Kong market’s total turnover, according to data announced by the Hong Kong bourse.

In 2017, the proportion stood at around 6 per cent, up from 3 per cent in 2016.

For now, negotiations are afoot to remove the block, although chances are slim for mainland Chinese investors to access Xiaomi - or any other large WVR listings in Hong Kong - in the near term while the mainland stock markets remain in the doldrums, said the Shanghai exchange official who declined to be named.

Chan is concerned “about the announcement by Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges to exclude the WVR companies from the Stock Connect,” said Christopher Cheung Wah-fung, the lawmaker who represents Hong Kong’s financial industry, recounting a 30-minute meeting on Monday with the financial secretary. “He has promised he would try his best to find a solution that would benefit both Hong Kong and the mainland markets.”

With additional reporting by Enoch Yiu in Hong Kong