Opinion | There’s no optimal staff turnover; hang on to your workers for dear life

Research shows the fresh ideas brought in by new hires is not enough to overcome the loss of skills that disappear with the leavers

Managers spend considerable time, energy, and money managing retention or labour turnover. Hong Kong’s economy is historically strong. In economic environments like ours, employees often have the choice to stay in a job or find other employment.

These economic conditions create challenges for decision makers. Should companies invest more or devise other ways of retaining employees in order to improve company performance? Or should they simply live with high turnover and work to replace leavers in an efficient and effective manner?

One approach to answering these questions is to consider whether science offers any insight, in particular, what does science say about how turnover affects company performance?

When a few employees quit to take other jobs, they take with them sizeable chunks of wisdom

Clearly, the answers can be complex and any general conclusion cannot cover all situations. But after studying these issues for more than 20 years, I believe our knowledge about how turnover affects performance is deep and often different to what is commonly believed.

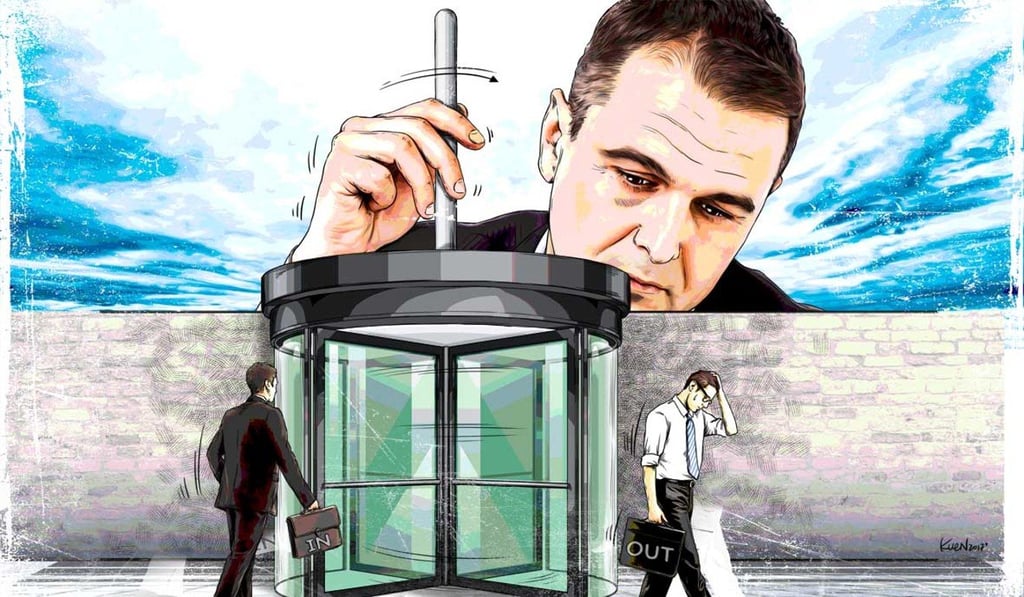

Many years ago at a holiday dinner, a relative asked me what I was studying at university. I informed him that I was investigating whether turnover related to company performance. To my surprise, my relative immediately launched into a long lecture that included his theory of the relationship. I don’t remember all of the details, but I do remember his key example was the image of dead wood clogging the river. Once the logs were cleared, water once again flowed freely. Therefore, my relative argued, some turnover improves company performance, but too much is dysfunctional. As it turns out, these ideas are commonly accepted among researchers and practising managers alike. Known in academia as the optimal or functional turnover view, the idea is that some turnover improves performance because new ideas, opinions, and energy are brought into the group. Too little turnover leads to stagnation and inertia, a sameness day after day that results in low performance. But too much turnover creates chaos and disruptions.

Why is this the case? There are two reasons.