How does China, the largest commodities buyer, become a price maker? Owning an offshore exchange is a start

China is hoping to have a long-term say in setting commodity prices as it looks to cut the dominance of exchanges in Chicago, London and New York

As the trade war with the US heightens concerns over the security of supplies – from soybeans to technologies – to the world’s biggest factory, China is building its first offshore commodities exchange, which it hopes will buy it a voice in influencing global prices beyond the ongoing dispute.

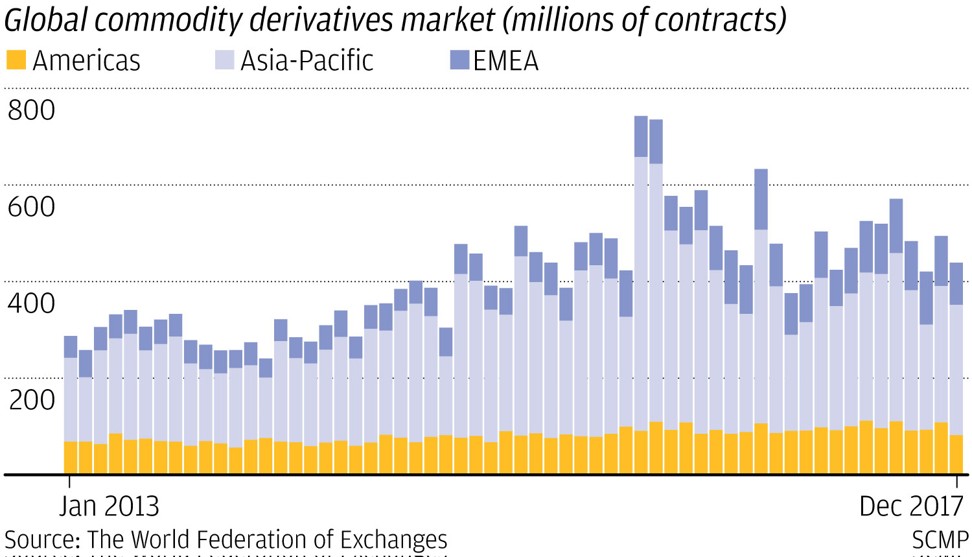

Mainland China is the world’s biggest consumer of raw materials from energy to agriculture products, but it remains a price taker at the mercy of traders in Chicago, New York and London, as well as Dubai where futures prices are fixed.

To change the game, China has established the Asia-Pacific Exchange (Apex) in Singapore, led by Eugene Zhu Yuchen, former chief of the Dalian Commodity Exchange, China Financial Futures Exchange and Shanghai Pudong Development Bank. Apex launched its first derivative product, palm olein futures, in May, and Zhu is setting a five-year timeline to make a global mark.

“Even though we have a successful commodities market [at home], our market is not internationalised, that is, we don’t have the power to set prices,” said Zhu, pointing to the three domestic commodities exchanges that allow minimal foreign investors to access.

“Without that ability, we feel like we are constantly in combat on someone else’s turf.”

“Processing factories in China are nearly one and the same. Which one does better depends on how well it controls commodity futures costs,” Zhu said. “Its success or failure rests on controlling that cost. A wrong take can result in its collapse.”

Chinese factories are highly reliant on imported commodities to meet demand. The country imports about 60 per cent of its oil; half of its iron ore and copper; and nearly all of its soybeans (90 per cent), a commodity at the heart of the US-China trade war.

So long as China remains the world’s biggest manufacturer, albeit cutting overcapacity in the current economic slowdown, its enormous demand for raw materials will not abate.

Building trading volume with foreign participation on Apex is arguably Zhu’s biggest challenge: pitting it against century-old exchanges like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) and the London Metal Exchange (LME).

Apex’s pitch, Zhu said, was built on what China’s onshore exchanges hamstrung by capital account controls, do not offer, and as the gateway to the coveted vast Chinese market. Foreign investors are limited to trading crude oil futures on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange and iron ore futures on the Dalian Commodity Exchange.

To gain access, they must open special onshore bank accounts over a lengthy process Zhu said, and would have to trade according to unfamiliar Chinese rules not totally aligned with international standards.

“The other option is Apex … based in Singapore, where the international trading crossroads are.”

Most of Apex’s current trade stems from Chinese customers but the exchange is targeting international investors who want to sell to China products it needs, to build the volume needed to win a voice over price discovery.

Without that [pricing] ability, we feel like we are constantly in combat on someone else’s turf

“In short, products that account for China’s largest trade volume – where plenty is transshipped via Singapore; Asia has a production advantage (such as palm oil and rubber); and related to the internationalisation of the yuan,” he said.

The development and success of any new product is no easy feat, as any exchange can attest to. Investments from research and development to testing and marketing can be daunting, and then they must withstand the test of fierce global competition.

For decades, China has depended on its trading partners for its supply of goods. As it moves its manufacturing up the value chain under the strategic Made in China 2025 plan, its vulnerabilities from that reliance increases, as does national interest to protect security of supplies. While a global exchange is an option, Apex also bodes the question if it can be a credible marketplace when China is both the operator and biggest customer.

Michael Syn, head of derivatives at the Singapore Exchange (SGX), a competitor, said there was no reason it cannot.

“The US is the world’s largest producer and they are the world’s largest marketplace. They are a net player and they operate the marketplace,” he said. “The reason they have been able to do that is because they have demonstrated track record running a fair marketplace.”

Syn said three factors would draw global investors to Apex: the desire to establish in China – “first in market”; arbitrage opportunities; and a seller who has an oversupply and wants to offload its goods.

“If he [Zhu] succeeds in creating a new marketplace here, that’s a win for us,” he said.

As much as Apex will be a rival, it can also bring in additional revenues for inter-market hedging opportunities for traders, who would trade on both exchanges. The exchange is 51 per cent owned by Zhu, 20 per cent held by CEFC China Energy and another 20 per cent by Xinhu Group.

It will be a long way for China to eventually win the pricing power of global commodities ... because there’s still some gaps of the economic power between China and the US

Zhu agreed.

“When Dalian [exchange] launched palm oil 10 years ago, Bursa Malaysia was worried. But not only did it not affect Bursa, it also helped raised Bursa’s volume,” he said. “Many investors trade on both markets – buy in Dalian, sell in Malaysia; many for gains.”

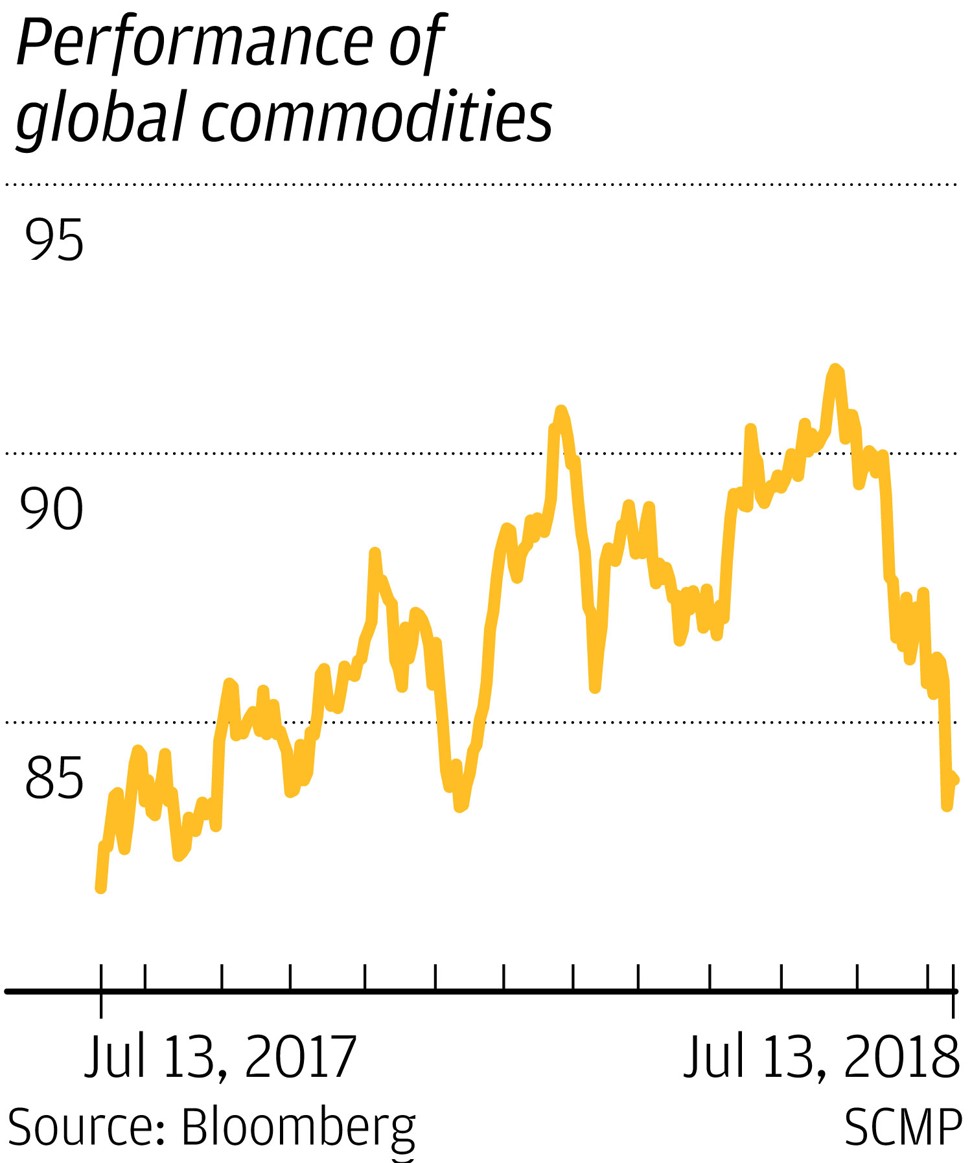

The first trading day of Apex’s US dollar-denominated physically delivered palm olein futures saw a robust US$33 million worth of contracts changing hands. Palm olein is a liquid form of palm oil used in cooking and baking. The fanfare has since subsided. The derivative traded at US$557.50 per metric tonne on Monday, down 12 per cent since the contract debuted on May 25.

“It will be a long way for China to eventually win the pricing power of global commodities, and that’s not an easy job because there’s still some gaps of the economic power between China and the US,” said Chen Hao, a strategist at KGI Securities in Shanghai.

“What China is doing now, such as setting up regional commodity and equity exchanges, will have a more direct and immediate impact on its Belt and Road programme and the internationalisation of the renminbi.”

“We import [the most] soybean, but we have to listen to Chicago, which isn’t reasonable,” he said. “At least for these products [where Asia is the biggest buyer], we should have our voice. Not the complete say as that would be unreasonable; we aren’t eliminating the US.”