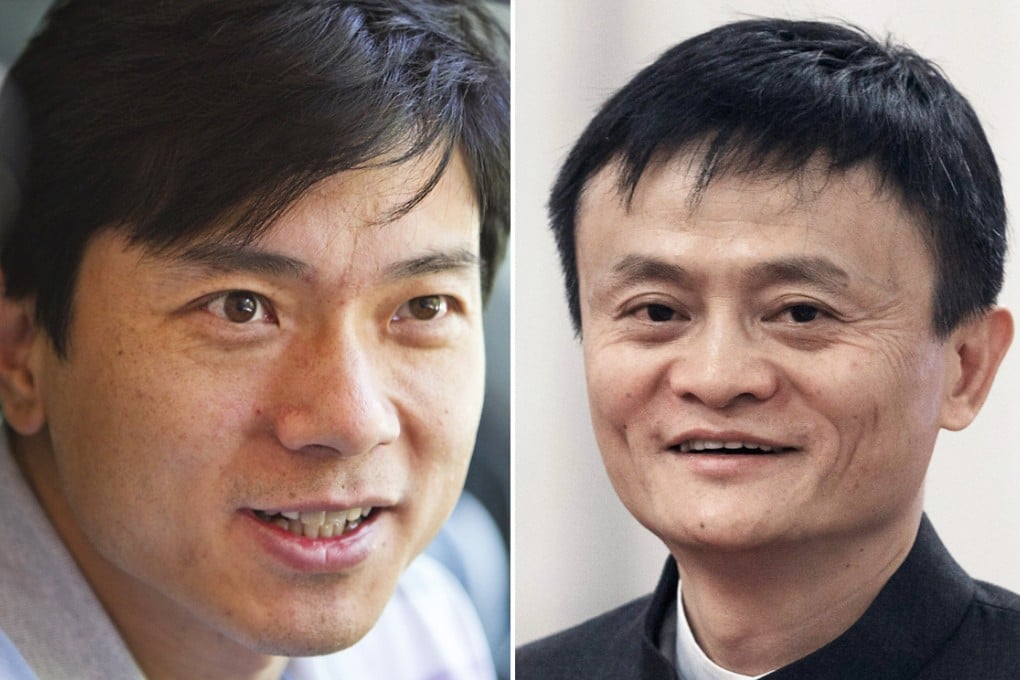

China's rich are less likely to keep business in the family – unlike Hong Kong’s wealthy

Unlike elsewhere in Asia, first-generation entrepreneurs in China are less likely to pass down their companies to their descendants

The relatively recent creation of wealth on the mainland and the nation's one-child policy have resulted in wealthy mainlanders being less inclined to leave their businesses to their descendants, compared with business families in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia.

said earlier this year there were 152 billionaires on the mainland and 45 in Hong Kong.

"I see many Hong Kong families sticking with traditional preferences in passing down the family business, while many from [the mainland] do not," said Clifford Ng, a partner at Zhong Lun, a mainland law firm that serves wealthy clients.

"The new billionaires in China are generally very open-minded about their legacy. They have seen how wealth can destroy families and family disputes can destroy businesses.

New billionaires in China are very open-minded about their legacy

"While cultural preference in inheritance may play a role, [mainland] clients recognise that the success of their business relies on meritocracy, and the child may not be the best person to run the business or, conversely, running the family business may not be the child's best career option."