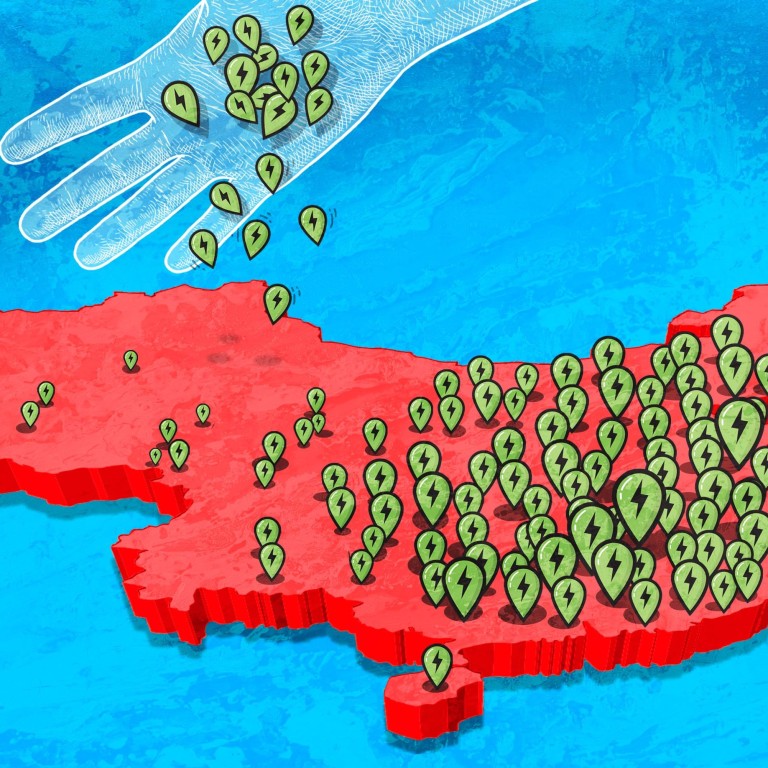

China’s EV charging problem: can providers deliver power where cars need it across the vast nation, and turn a profit?

- Charging points are proliferating quickly but are unevenly distributed: too many in large cities and too few in less populated areas

- Meanwhile, despite record EV sales, the largest operators of charging networks struggle with utilisation so low that profit seems nearly impossible

A tale of two drivers.

As China leads the EV revolution with a 60 per cent share of global electric-car sales, the country’s deployment of charging infrastructure is also rushing forward at breakneck pace. However, the experiences of Jiang and Hou point to the next big challenges for both policymakers and commercial charging-point operators. Uneven distribution of charging facilities across the vast nation, as well as uncertainty over the viability of charging as a business, cast doubt on whether China’s charging infrastructure can provide enough juice to continue powering the electric revolution.

As of the end of September, China had on its roads 18.2 million new energy vehicles (NEVs), a category that includes battery-powered EVs (BEVs), plug-in hybrids and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, according to the Ministry of Public Security.

And China is quickly rolling out charging infrastructure at an impressive scale, said Abhishek Murali, senior analyst at energy research consultancy Rystad Energy. The number of charging points reached 7.6 million at the end of September, a 70 per cent year-on-year increase, according to the China Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Promotion Alliance (EVCIPA).

Aiding that buildout, most popular Chinese EVs are on the small side, which means smaller, less expensive charging equipment has been sufficient, Murali said.

The national ratio of EVs to charging points currently stands at 2.5:1, versus 3:1 a year ago. But China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has more ambitious goals: it wants the ratio to reach 2:1 by 2025 and 1:1 by 2030. Major cities, including China’s EV hubs Shenzhen and Shanghai, have also laid out plans to expand and upgrade their charging infrastructure.

In Shanghai, Jiang does not own a charging point at home; he goes to the nearest petrol station every morning for the EV chargers installed there. While he works driving passengers around the city, he pops into the underground car park of a shopping centre when his car needs a charge. As an EV owner, he can enjoy two hours of free parking there.

“Within a radius of two kilometres, you can find 10 to 15 EV charging stations when driving in Shanghai,” Jiang said. “No one worries about charging.”

Jeep, Fiat owner buys US$1.6 billion stake in Chinese EV maker Leapmotor

EV drivers in less populated regions would beg to differ.

“China’s public charging infrastructure is unevenly distributed,” said Shen Fei, senior vice-president of power management at Chinese EV maker Nio. “There are more charging points in urban areas than in rural areas, more in the eastern provinces than in the west.”

In fact, more than 70 per cent of China’s current public charging points are located in 10 of the most economically developed provinces and municipalities, including Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shanghai and Beijing, according to EVCIPA.

That uneven dispersal is not surprising, as it mirrors the distribution pattern of electric-car ownership. However, the high density of chargers in urban areas leads to underutilisation. Meanwhile, charging stations deployed along highways and in rural areas can be underused much of the time, only to fall short of meeting demand during holidays when more people travel, according to Shen. Lack of charging options can also deter EV sales in those areas.

Only about 30 per cent of the charging points in China are public, which equates to 2.5 million chargers managed by commercial operators and installed along roads, in car parks, at restaurants and at other businesses, according to EVCIPA. The rest are private charging points installed at homes or reserved for business employees or fleets.

Yet general underutilisation of chargers means profitability is a struggle for commercial operators, especially given high capital expenditures on equipment, installation, software, maintenance and training of service personnel.

China’s biggest EV charging network, TELD, which has over 466,000 charging points nationwide as of September, reported in April a net loss of 26 million yuan (US$3.6 million) for 2022 – its fourth consecutive annual net loss. TGOOD, the Shenzhen-listed parent company of TELD, attributed the loss to infrastructure spending and the low profit margins that generally apply to the EV charging business.

StarCharge, the second-largest public charging network in China, with about 419,000 charging points, is estimated to consume only around 40 kilowatt hours (kWh) of power per day per charging point, with a daily utilisation rate of 8 per cent, meaning its average charger is used for fewer than two hours a day, according to Rystad Energy.

The company’s financials are unknown as it is a private company, but Rystad estimates that with pricing of US$0.20 to US$0.25 per kWh, 40 kWh of consumption yields daily revenue of only US$10 per charging point, far below the cost of buying and delivering the electricity, not to mention making up for capital expenditures.

Thailand moving full speed to lure China’s EV ‘big fish’ to ‘Detroit of Asia’

“One way to recover these costs is to charge more for electricity consumption,” Murali said. “However, this can discourage consumers from using public chargers, especially when compared to the cost of charging at home.”

The current public charging market is still heavily reliant on facility utilisation and charging volumes to make profits, according to Liu Bo, founder of KeyCool, a Shanghai-based public charging network operator with around 10,000 charging points nationwide. Although advertising and government subsidies provide a small amount of revenue, it is urgent for operators to diversify their business portfolios, Liu said.

China’s current charging market is also crowded, as many players have jumped in with the expectation of future growth, according to Ivan Lam, senior analyst at Counterpoint Research. A lack of standardisation among charging stations, a lack of planned expansion and construction, and the high growth of the EV population also contribute to the shortcomings of the overall network, he said.

Leading operators continue to rapidly expand. TELD says it added 111,000 public charging points last year, increasing its total by 40 per cent over 2021. Data from EVCIPA as of last month showed that China’s 15 biggest operators account for 92 per cent of the market. That leaves around 3,000 other operators battling over the remaining 8 per cent, according to the National Energy Administration.

“As the number of charging stations and charging points for leading players increases, along with the orderly operation and improved profitability, we believe the long tail will gradually fade away,” said Lam.

The central government is pulling on policy levers to improve the sector.

Xpeng aims to make smart driving technology available across China by end-2024

China’s top economic planner, the National Development and Reform Commission, is actively addressing charging infrastructure in a bid to boost EV sales, especially in rural and lower-tier regions. It has urged local governments to offer financial incentives for the construction of new EV charging stations in counties and villages, as well as along rural highways.

The State Council released guidelines in June calling for digitalisation and the introduction of smart technologies, including the ability for car batteries to give power back to the grid, which could address supply concerns and improve power system stability.

Incorporating data, artificial intelligence and analytics into the planning and deployment of EV charging infrastructure could increase efficiency and utilisation while reducing operator costs, according to Alex Wu Xuelu, co-founder, president and CFO at NaaS Technology, one of China’s largest EV charging service providers.

“Sometimes there’s a misconception or oversimplification when we say the ratio between EVs and chargers has to reach 1:1,” said Wu. Solving the charging issues in China requires “dynamic balancing” between the charging network and fast-growing EVs, and requires EV manufacturers and local governments to work with infrastructure operators early in the planning process to provide reliable data and generate insights, he said.

Despite the challenges operators face, energy companies and carmakers remain bullish on the outlook for China’s EV charging market.

Chinese carmakers lead in EVs, lag in decarbonising supply chains: Greenpeace

In September, Shell opened its largest EV charging station globally in Shenzhen. The facility has 258 public fast-charging points and can serve more than 3,300 EVs a day. Shell also opened an integrated energy station in Wuhan the same month. It offers a wide range of mobility products and services, including petrol and diesel, EV charging, hydrogen refuelling and car-wash facilities.

Charging point operators have also been able to increase prices recently. State news outlet Xinhua reported last month that prices at some charging stations in Shanghai have almost doubled over the last couple of months.

Shanghai-based driver Jiang said he is not concerned.

“It’s still cheaper than gas,” he said. Although he drives a plug-in hybrid, he now mostly uses it as a pure EV.

“In Europe, people are happy to pay for premium service,” said Wu at NaaS. “I believe in China, that will be our future one day.”