As Evergrande, Kaisa and other Chinese developers fall on hard times, Hong Kong’s bargain hunters swoop in

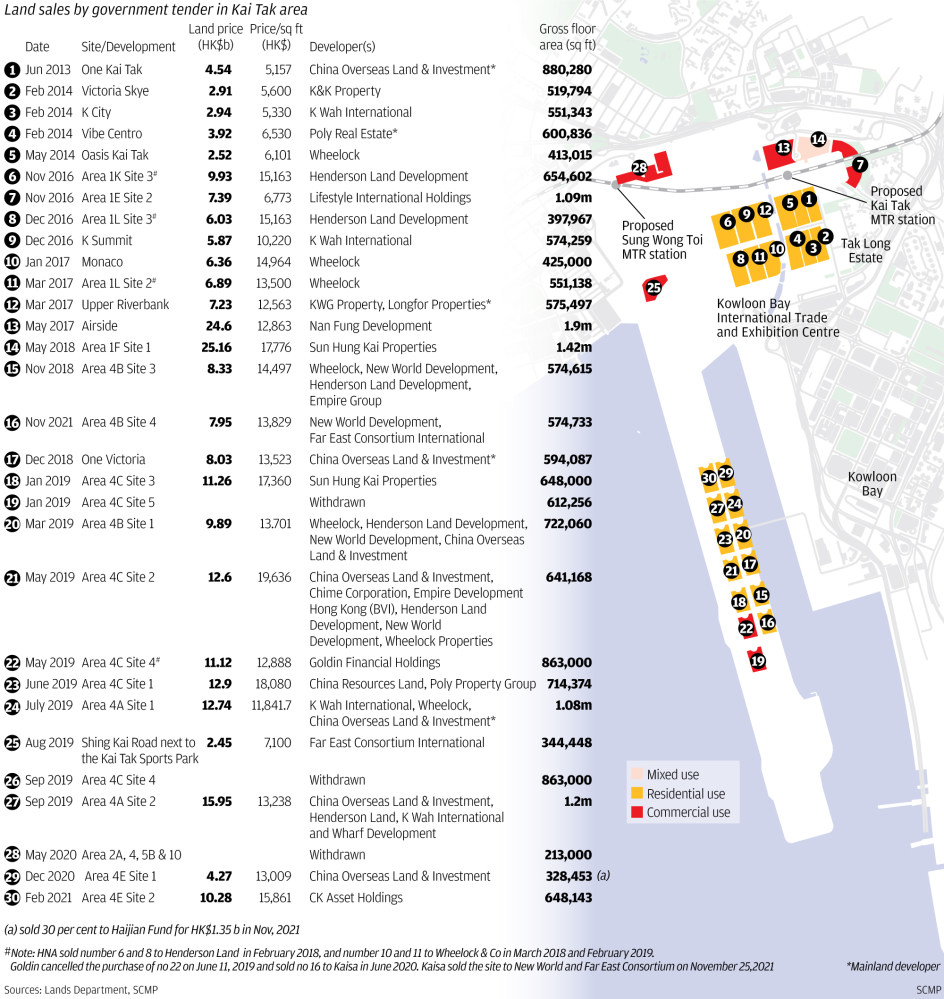

- Mainland Chinese developers bought seven sites each year during the Hong Kong government’s 2016 and 2017 land sales programmes

- By 2018 and 2019, their activities had dwindled to three each year, with only one deal so far in 2021

The HNA Group, a conglomerate built around Hainan Airlines, paid a record HK$8.84 billion (US$1.13 billion) for a residential land plot at Hong Kong’s former Kai Tak airport, paying substantially over the market’s valuation. It was the opening salvo in a HK$27.22 billion shopping spree over four months that ended with HNA owning four parcels of prime land, each setting a fresh price record.

“Mainland companies have the ability to do it, but we don’t,” Lui said in a November 24, 2016 interview with the Financial Times, adding that the flood of money from Hong Kong’s northern border was “distorting” the city’s land prices.

“Fierce competition for land is unavoidable in government tender exercises, and it’s hard for small players like us to get prime sites,” said Wang On’s chief executive Nick Tang Ho-hong, the son of the firm’s controlling shareholder Tang Ching-ho.

Elsewhere in Hong Kong, mainland developers were busily grabbing land, parking their capital in the city’s fixed assets to get ahead of what was then a depreciating renminbi.

“Hong Kong’s assets are highly liquid, compared with property in mainland China, especially those in lower-tier cities,” said Yan Yuejin, director of Shanghai-based E-house China Research and Development Institute. “They are a life-saving straw for Chinese developers struggling to survive the winter of China’s real estate sector.”

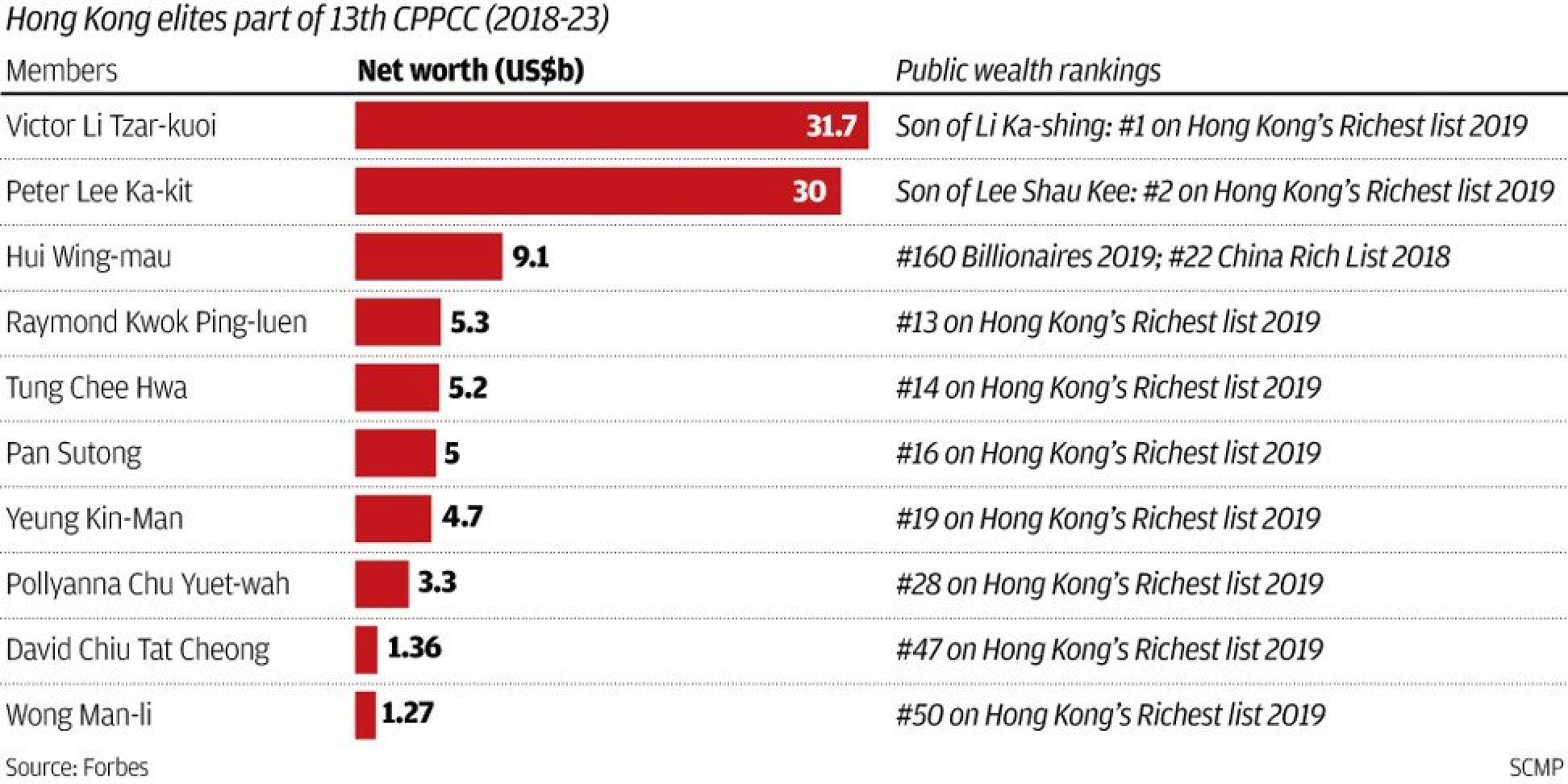

“Major Hong Kong developers have lots of ways to reflect their views to Beijing at the National People’s Congress (NPC), or through Chinese officials [stationed] in the city,” said Lau Shui-kai, vice-president of the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau.

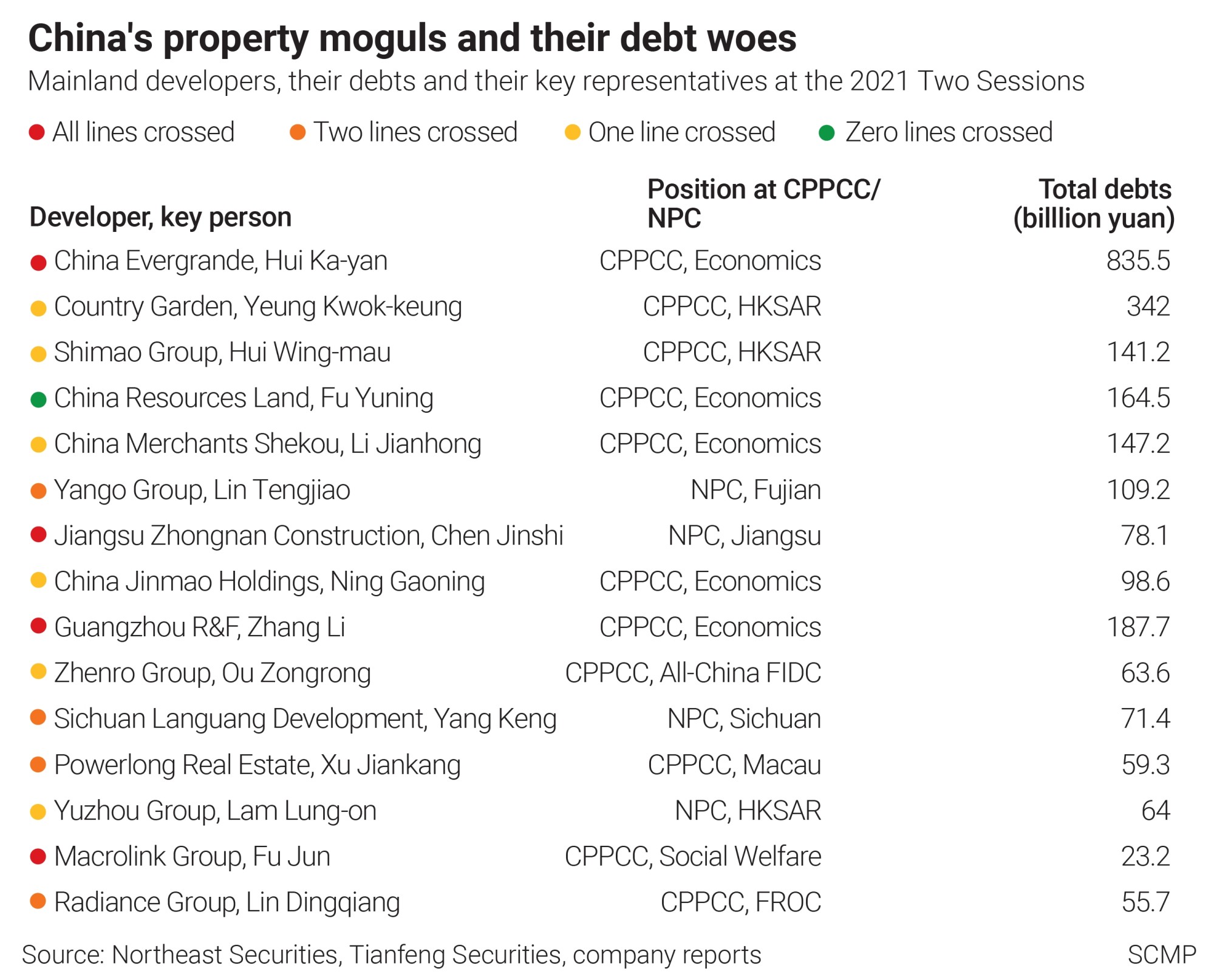

Led by the property magnate Hui Ka-yan, with businesses from bottled water to electric cars, Evergrande has been trying to sell its assets in Hong Kong to service its debt.

Hui, whose wealth was estimated at US$9.1 billion by Forbes, has put some of his personal assets on sale to repay Evergrande’s debt. Three adjoining mansions of up to 5,400 square feet each at 10 Black’s Lane on The Peak in Hong Kong were remortgaged last month for HK$1.1 billion in financing.

Kaisa, with US$11.6 billion of outstanding notes, disposed of two land plots and an office floor in Central for about HK$12 billion within three weeks, the most aggressive seller of assets in Hong Kong in the past month.

A week later, Kaisa sold a Kai Tak plot to New World Development and Far East Consortium for HK$1.9 billion cash and HK$6 billion in assumed debt, according to a stock exchange filing.

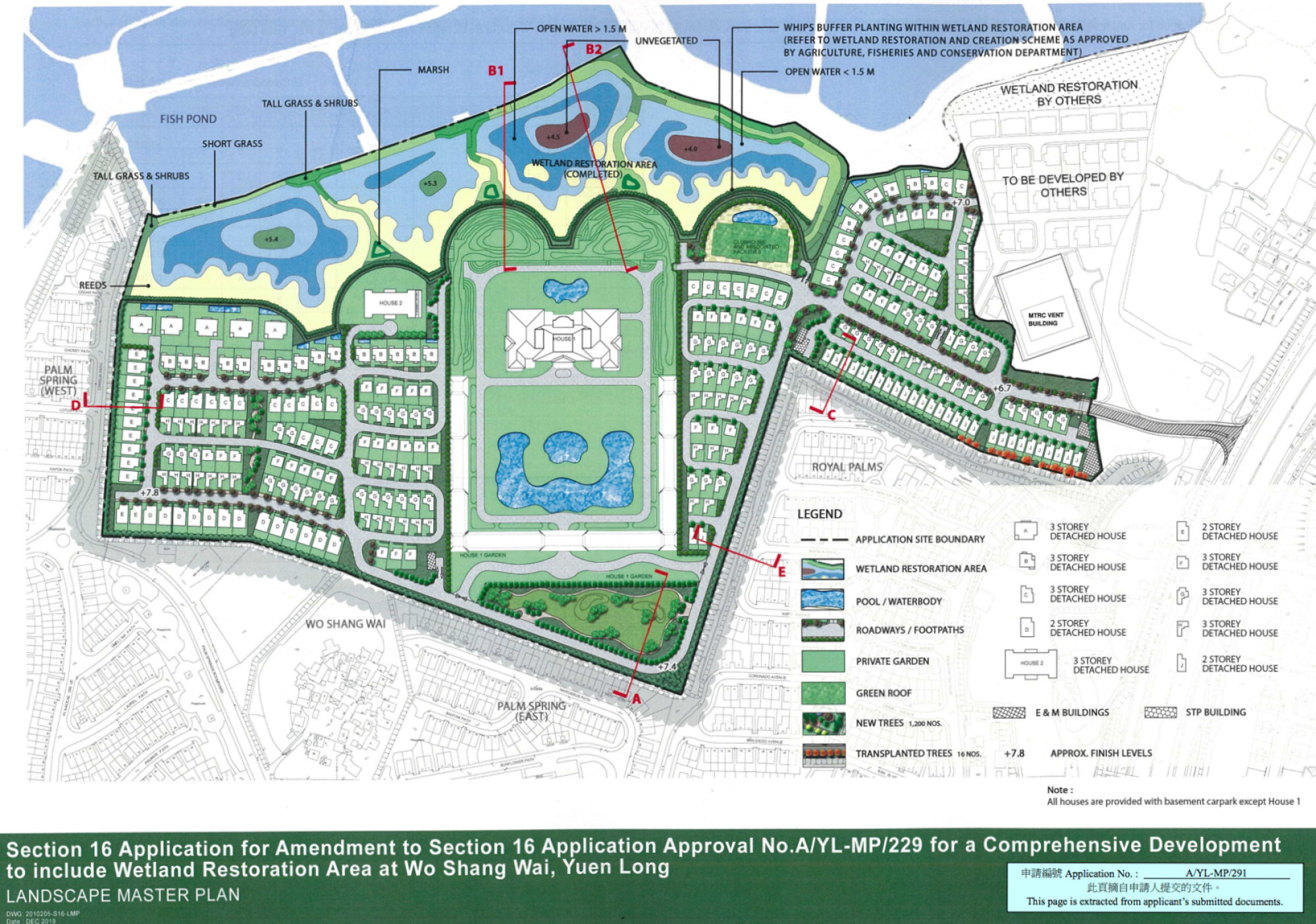

The waterfront plot, known as Area 4B Site 4, is located on the narrow strip of land protruding into Victoria Harbour that was formerly used as the airport’s runway. Kaisa had bought it last year from the Chinese billionaire Pan Sutong’s Goldin Financial Holdings, which was grappling with its own debt woes.

Aoyuan, based in the Guangdong provincial capital, had been holding fire sales of its Hong Kong assets.

The losses reflected the reckoning for Chinese developers, who preferred to subdue their rivals by paying way over market valuations. HNA’s first Kai Tak plot in November 2016 was a staggering 153 per cent over the most recent transaction in the neighbourhood two years earlier.

Kaisa’s first land plot in Tuen Mun was bought last year for HK$3.5 billion, 20 per cent more than the next bid at HK$2.88 billion, according to records released by the Lands Department. The developer had wanted to show Hongkongers what Kaisa was made of, regardless of the cost, a former employee said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

After the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) ordered the city’s banks to cut their property loans by 10 percentage points to 40 per cent of a land plot’s assessed value, the activity dwindled by half to three a year by 2018 and 2019.

HNA’s four Kai Tak plots all ended up in the hands of Hong Kong’s major developers. Wheelock Group, run by Douglas Woo – son of Hong Kong tycoon Peter Woo Kwong-ching – picked up two pieces of land from HNA for HK$13.25 billion. Henderson Land Development, owned by the family of founder Lee Shau-kee, picked up another two sites for HK$16 billion in total.

The four sites totalled HK$29.25 billion, about 7 per cent more than what the Chinese developer paid for.

“We will not prohibit others from taking part in bids for the government’s land,” said Wheelock Properties’ chairman Stewart Leung Chi-kin, who also chairs the powerful lobby group Real Estate Developers Association (Reda). “Hong Kong is a free market.”