Flight of no return: How a Cathay Pacific plane became the first hijacked commercial airliner

In 1948, in an audacious plot involving guns, robbery and ransom, a Cathay Pacific plane became the first commercial airliner to be hijacked. It ended in disaster but, as Mark Footer recounts, a remarkable tale eventually emerged.

'Fantastic but true.' With those three words, spoken 60 years ago this month, the managing director of Cathay Pacific Airways introduced Hong Kong to the horror of skyjacking.

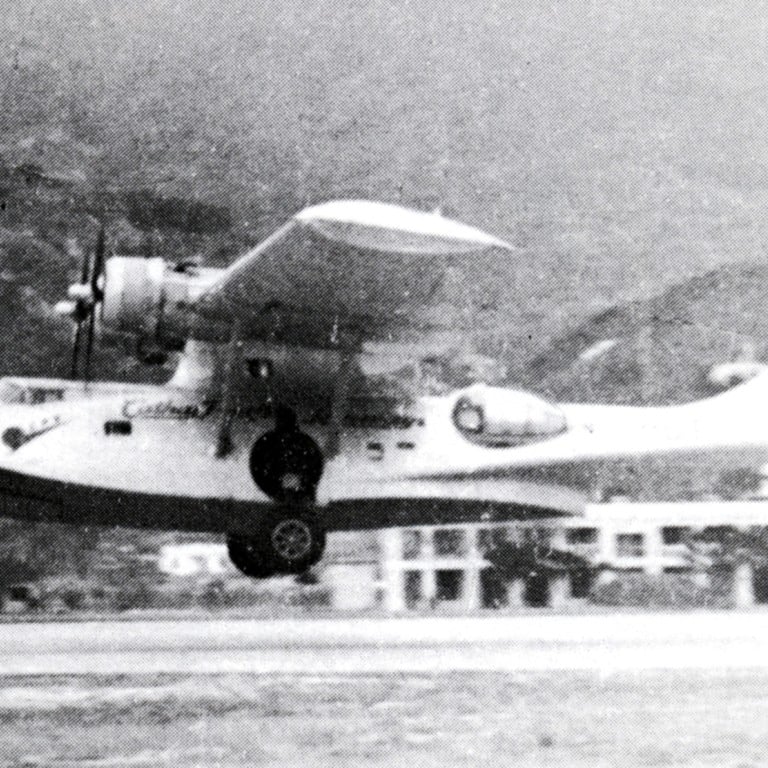

'Cathay Pacific Airways refrained from making a statement earlier as the facts were so fantastic that they appeared incredible,' Sydney de Kantzow continued on July 31, 1948, 15 days after one of the airline's Catalina amphibious aircraft, Miss Macao, plunged out of the sky in the first recorded incidence of piracy on a commercial airliner. The plane had crashed into the sea, killing 26 of the 27 people on board.

Cathay Pacific was in its infancy in 1948, having started as the air transport wing of the Roy Farrell Export-Import Company, established in Shanghai in early 1946 to fly in from Australia anything the entrepreneurial American could sell.

The operation began to ferry passengers as well as freight and expanded at a furious pace. A passenger ticket office opened for business in the lobby of The Peninsula hotel in Hong Kong and an office was rented at 4 Chater Road by de Kantzow, an Australian who had first met Farrell when the pair were pilots flying 'The Hump', the name given by Allied pilots in the second world war to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains. Between April 1942 and 1945, pilots such as de Kantzow, who was employed by the China National Aviation Company, flew from India to China to resupply the Flying Tigers - volunteer American pilots attached to the Chinese Air Force - and the government of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

Once, during the British retreat from Burma, de Kantzow managed to evade 15 Japanese Zero fighter planes while flying 'Gimo' (as Chiang was affectionately known), Madam Chiang and US general Joseph Stilwell to Kunming. 'He was a stern almost uncompromising perfectionist. He was a brilliantly outstanding pilot and we were convinced he could actually fly the boxes the planes came in,' says Charles 'Chic' Eather, an Australian pilot who joined the fledgling airline in December 1946.

As Farrell's business boomed, Hong Kong became an increasingly important centre of operations - it was geographically well placed and an increasingly volatile mainland was becoming less and less attractive as a base - and it wasn't long before Farrell and de Kantzow decided to make theirs a Hong Kong-registered business. However, there was a snag: as a British colony, the business had to be two-thirds British owned.

Being Australian, de Kantzow counted as British so by bringing in one other, Neil Buchanan - an Australian ex-squadron leader originally employed by Farrell to run his company's Sydney office, the trio were - with help from the accommodating A.J.R Moss, Hong Kong's director of civil aviation - legally allowed to form a new company.

According to Gavin Young's Beyond Lion Rock: The Story of Cathay Pacific Airways, which the airline points to in reply to questions concerning the skyjacking, the articles of association of the company were drawn up on September 24, 1946, having been signed the day before by Farrell and de Kantzow. At the time of the Miss Macao incident, the ownership of what was now Cathay Pacific Airways had recently altered; on June 1, 1948, John Swire & Sons and Australian National Airways ratified an agreement to help run the airline.

'The CX [the International Air Transport Association company code for Cathay] of the time was a small, closely knit family,' recalls Eather, who lives with his wife, Judy, in Surfers Paradise, Australia. 'Everyone knew each other and combined family activities - for example, on April 29, 1948, [the crew members who went down with Miss Macao] attended the marriage of our popular sales and traffic officer Robert Lowich Frost and Angeline de Gardner. That particular occasion completely closed down the airline for the day. Think of the confusion that would cause if it were practised today.

'CX housed its single personnel in a 'comfortable' mess located at 28 Grampian Road, Kowloon. It was well lived in and on occasions resembled a garbage pit. Yet, we loved it. CX accommodated the married men in a rambling building in Mody Road, Kowloon, grandly named The Melbourne Hotel. It was a carefree uncomplicated way of life.'

Cathay's two PBY Catalina flying boats had been bought, from the United States Air Force Federal Liquidation Commission in Manila, for a specific purpose. Hong Kong was prevented by the Bretton Woods Agreements - drawn up in 1944 to govern monetary relations between nations - from importing free gold but Portuguese Macau was not. Cathay realised a pretty penny could be made ferrying the gold that arrived in Hong Kong in the holds of other airlines to Macau for dissemination to, among others, Chiang, who needed money for his fight against the communists.

Macau had no runway and, according to Young, an experiment that involved tossing barrels of gold out of the side door of a DC3 aircraft as it flew low over the racecourse proved unworkable. De Kantzow then realised seaplanes were the solution. And so it was that the Catalinas, chartered to Macao Air Transport Company (Matco), a subsidiary Farrell and de Kantzow established with the Macau-born trader who owned Cathay's Chater Road office, P.J. Lobo, began making twice-daily round trips between Hong Kong and Macau, ferrying passengers and gold (but never together - 'for that mix is a prescription for disaster,' says Eather).

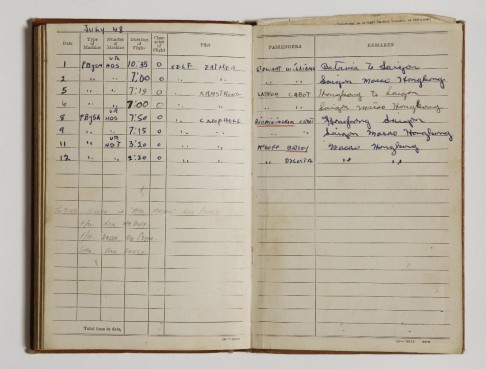

At 5.30pm on July 16, 1948, Catalina VR- HDT - piloted by American Dale Cramer, 27, known as a gifted softball player, with Sydney-born Ken McDuff, 23, as first officer and Delca da Costa, 22, as hostess, left Hong Kong for the final time.

Neither Cramer nor McDuff were originally rostered onto the flight, writes Eather in his memoirs, Syd's Last Pirate. (Eather had been the American's first officer two weeks previously; they had flown Cathay's other Catalina from Jakarta to Saigon, Macau and Hong Kong, carrying gold bullion for Macau's Banco Nacional Ultramarino.) On that fateful evening, Cramer was substituting for a pilot who had developed acute earache during the day while McDuff was filling in for the morning flight's first officer, who had tumbled into stinking muddy water when he had misjudged the mooring of the craft.

Another Cathay employee who 'shouldn't' have been on Miss Macao that day was Frost, recounts Eather. When journalist Alan Marshall, who was researching an article on da Costa for Woman magazine, pulled out of the round trip before departure from Kai Tak because his legs ached (Marshall suffered from polio as a child), Frost jumped at the chance of filling the only empty seat in the plane - to kill some time while his new bride had her hair done.

The communication systems airlines used in 1948 were primitive by today's standards (the report from the inspector of accidents, also Moss, following the incident, recommended 'an aeradio station be set up in Macao at the earliest possible date in order that definite point-to-point contact may be established between Hong Kong and Macao while flying is in progress') so the loss of the aircraft wasn't immediately realised.

Although staff began to get anxious when the plane didn't arrive as scheduled at 6.30pm at Kai Tak, it was not known, by anyone at the Hong Kong end at least, that disaster had struck until de Kantzow flew in the other Catalina to Macau the following day to find out what was going on.

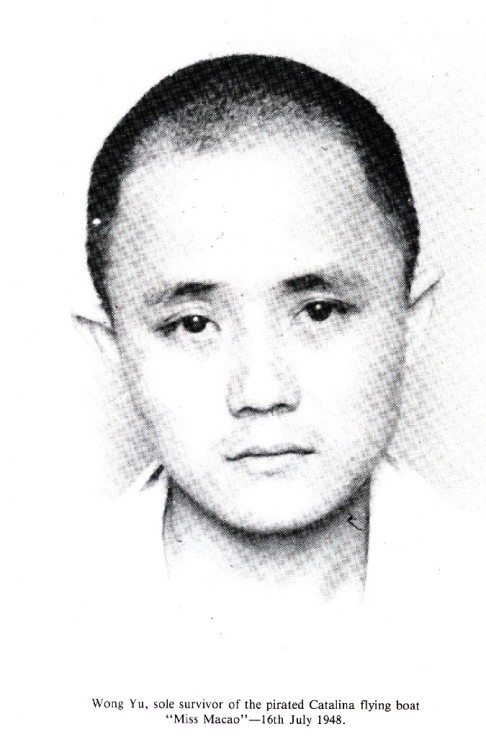

There he learned that an unconscious survivor, Wong Yu-man, had been brought ashore at 9.15 the previous evening by two fisherman in a motorised junk. Both fisherman said they had seen the aircraft fall from the sky after taking off on the return leg from Macau but neither could pinpoint the exact location. Thus began a search by vessels belonging to Macau water police, Chinese maritime customs and fishermen. A Royal Air Force Sunderland, a US Navy Martin Mariner and Cathay's other Catalina searched from the air.

The SS Merry Moller, a steamer on the Hong Kong to Macau run, was the first to come across wreckage, retrieving a wing float at 3.20pm on July 17. The first body found, the same day, was that of H.G. Stewart, who worked for of Texas Oil. It was plucked from the sea close to Macau's breakwater.

The wreck of the plane was finally found near Kau Chau (Nine Island), about 16km northeast of Macau, 'close to the normal track of the aircraft when flying north of Lantau Island', stated Moss.

His original report could confirm only 11 killed, the only one of the crew being McDuff, whose body now lies in Happy Valley Cemetery. Young writes: 'The fact that he was comparatively unmarked meant, said Moss, that he could not have been in the pilot's compartment at the time of the crash, for the compartment was completely wrecked.'

The mystery deepened and the one survivor, described in early newspaper reports as 'probably the poorest among the passengers' and who was in hospital in Macau with a fractured right arm and fractured right leg, wasn't talking.

Salvage work continued, interrupted for several days by a typhoon, until the discovery of spent bullet casings in wreckage brought ashore and later in that still at sea gave rise to new speculation. However, it wasn't until July 26 that the South China Morning Post began giving consideration to 'the air-piracy theory now being advanced'. The revelation, by Macau police commissioner L.A.M Paletti, that four millionaires went to their deaths on Miss Macao bolstered that theory. The wife of one had told Paletti her husband was carrying HK$500,000 when he boarded the plane.

Amid the confusion, the Post reported: 'Paletti said that a pirate gang might have plotted to force the plane down, capture and ransom the four wealthy men. He said that of the five men suspected of being involved, one was a Chinese air pilot.'

The truth was eventually extracted from the sole survivor, who had come to be viewed with suspicion. 'At first he was incoherent,' writes Young, 'so a recording device was concealed near his hospital bed. In addition police officers disguised as patients were placed in neighbouring beds, and from time to time elderly 'relatives' came to sit by them and hold their hands. In time Wong told all he knew, and from his confession and from the Al Capone-style clothing of his three confederates ... Captain Paletti and his men were able to round up six or seven other Macao Chinese for questioning.'

The plan had been to hold up the plane, force it to land somewhere remote and rob the passengers. They could then be held on a remote island by relatives of the pirates and ransomed.

According to Eather, there were initially three conspirators in the plot: Chio Tok, Chio Kei-mun (who had an opium habit and would be replaced by Siu Chek-kam) and Chio Cheong, all of whom came from the village of Nam Mun, on the southeast coast of Tao Mun (Doumen; due west from mainland Macau and now part of Zhuhai). Wong, the survivor, was a 24-year-old rice farmer who had been brought into the plot because of his detailed knowledge of the coastline and places where a hijacked Catalina might be hidden.

The gang plotted at the 'home of 29-year-old Chio Iek-chan, a pretty deserted wife living ... at 39 Rua Coelho do Amaral', writes Eather, who explains that her sister - '37-year-old Madame Vo, who was tall, thin and ugly with a well-defined streak of larceny and the disposition of a shrew' - was an accomplice. The Post described the area in which Chio Iek-chan lived, Chung San (Guia Hill), as 'the famous pirate district of Macao'.

Chio Tok had learned to fly Catalinas in Manila and, with the others, had studied Matco's flight path between Macau and Hong Kong.

On the morning of July 16, according to Eather, the men spent 20 patacas along Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro on lightweight 'European' clothing. Three of the four well-dressed gang members who boarded Miss Macao carried handguns and Chio Tok and Chio Cheong made sure they sat behind the pilots. Seven or eight minutes after take-off they struck - Chio Cheong covered McDuff while Chio Tok demanded Cramer hand over the controls. Cramer, an ex-US Navy pilot, refused to budge. McDuff took advantage of the standoff by taking a swing at Chio Cheong with a mooring flag.

Then all hell broke loose and shots were fired. It is likely some of the passengers intervened - the body of one of the Chinese millionaires was found with a bullet wound.

Young writes: 'It's not difficult to imagine the pandemonium in that confined space: the cries of anger and the screams, the shots, the smell of cordite, the struggling bodies in the aisle.'

However it played out, during the melee, Chio Tok shot Cramer in the head and body and the pilot slumped over the controls, sending the aircraft into an irredeemable dive.

Among the 23 passengers who perished in Miss Macao was Genady Moskevitch, ringmaster of the Kamala Circus, who had been arranging a visit of the circus to the Portuguese colony and was to have travelled back by steamer. He reached the wharf too late so hurried to the seadrome and asked an assistant booked on the flight to give up his seat.

One of the millionaires aboard was Wong Chung-ping, who was said to be worth US$3 million and was part owner of the Hang Shun gold bullion firm in Macau. According to the newspaper Wah Kiu Yat Po, he had boarded Miss Macao carrying 3,000 taels of gold.

Also on board was a well-known local jockey, Major H.M.R Hodgman, and his wife, Celia. Hodgman was 'a regular horseman at Hongkong race meetings after the colony was freed [from Japanese occupation]', wrote the Post. 'He was often successful and had good mounts at almost every meeting.' Celia Hodgman was an accomplished singer and could be heard at concerts and on ZBW - as the radio broadcaster RTHK would be known until August of that year - performing with the Hong Kong Singers and the Sino-British Musical Group.

Others who perished included: Wong Chi-tat, a prominent merchant from near Guangzhou who had 'recently been appointed by the Kwangtung provincial government to undertake bandit suppression work'; Mrs N. Humphreys, the wife of a revenue officer of Hong Kong's Imports & Exports Department; Mr and Mrs D. Nelson and their two children, an American family on a tour of southern China; Wu Sau-man, a member of the Shanghai staff of the Coca-Cola Company, and his wife; the wife of Hong Kong teacher William Lai, who had put her two daughters on the Merry Moller but couldn't secure passage on the ship for herself; and a Mr F. Perreira, whose body, the Post noted, was found wearing a ring bearing the Chinese inscription for 'Lucky'.

'Following that witless murderous attack, we were devastated,' says Eather. 'However, the strong leadership provided by John 'Jock' Kidston Swire [the then chairman of Swire] and his brilliant team provided the necessary fortitude to get us quickly back into the air, where our misgivings were replaced by hard work and the realisation that life must go on.'

One might have assumed such a dramatic example of the damage criminals could cause would have led to the rapid development of countermeasures - but that was not the case.

'Regretfully nothing changed in respect to checking what items passengers carried when boarding,' says Eather. 'Of course, there were suggestions via letters to the newspapers of possible remedies. Syd de Kantzow suggested the installation of metal detectors at departure points.

'On March 29, 1974, I ferried a CX Boeing 707 from the Northwest Airlines base at Minneapolis. Aboard that flight were two security canopies that resembled a doorframe. This was Kai Tak Airport's initial foray into checking departing passengers for dangerous goods. This vindicated de Kantzow's suggestion (in a refined state) of more than a quarter of a century earlier.'

And what became of Wong, the rice farmer-cum-hijacker who lived to tell the tale?

'Neither Portuguese Macau nor British Hong Kong had legislation that covered piracy in the air,' explains Eather. 'Consequently, neither authority had the basis to try Wong Yu. On June 11, 1951, he was released from the Macau prison where he had languished for three years without trial. He went to China, where rumour had it his life was snuffed out in a suitably contrived accident. The Chinese authorities detested piracy whether on the sea, on the land or in the air.

'My thought and the feelings of my colleagues was that justice was done.'

THIS ARTICLE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN POST MAGAZINE IN 2008, ON THE 60th ANNIVERSARY OF THE HIJACKING