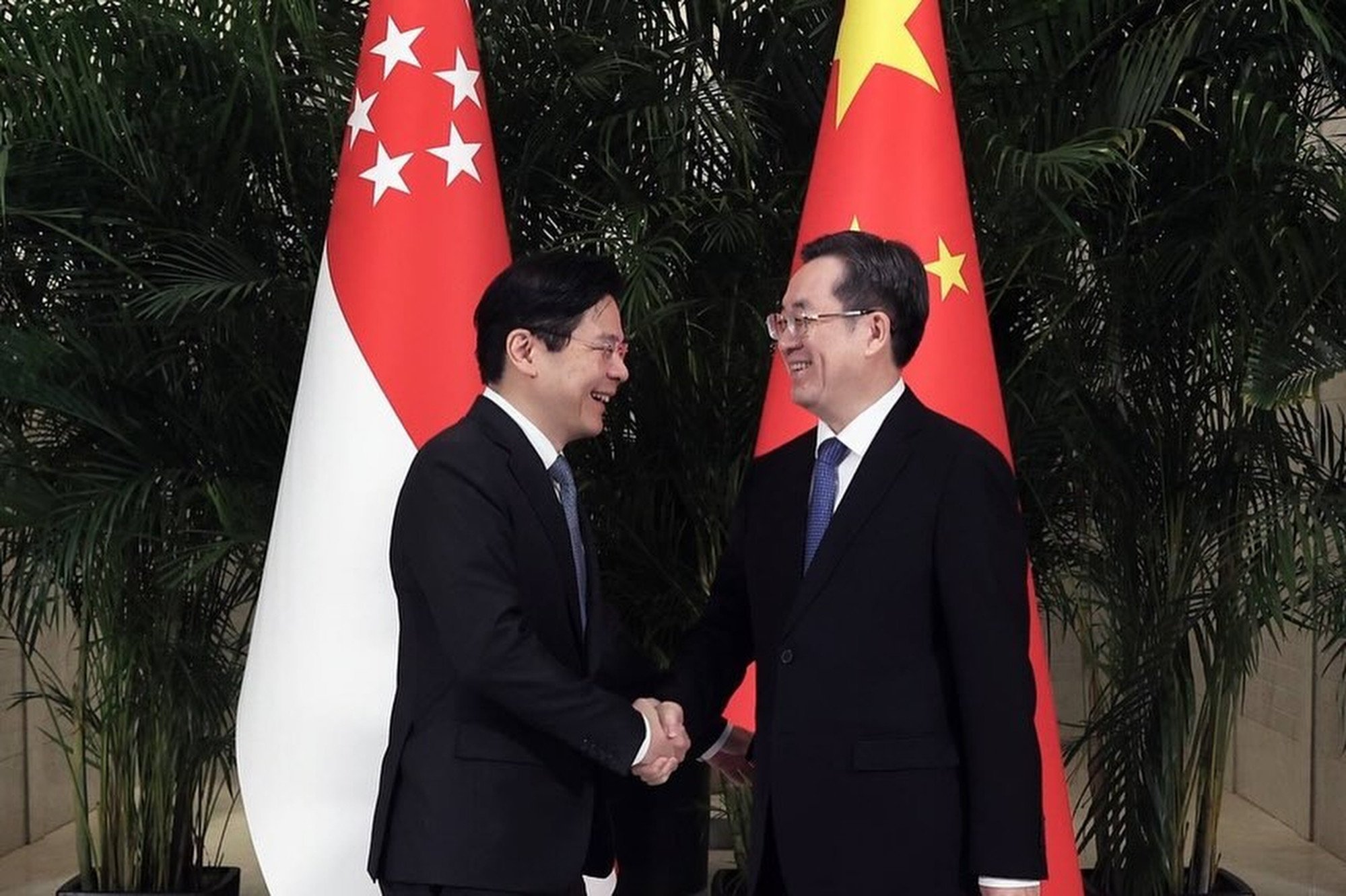

Are US-China ties in ‘challenging environment’ the biggest test for Singapore’s next PM Lawrence Wong?

- Navigating US-China ties will be Wong’s biggest test as PM, analysts say, in a volatile region increasingly influenced by major powers

- Singapore’s unwavering stance that is neither ‘pro-China’ nor ‘pro-US’ is a way of insulating itself from internal and external pressures, analysts say

Wong, currently deputy prime minister, shed light on his governance style in an interview with The Economist on Monday, reaffirming a “pro-Singapore” approach that was neither “pro-China” nor “pro-US”.

Analysts say navigating such a relationship will be the biggest test for Wong, as the tiny state finds its place in a volatile region increasingly influenced by bigger powers.

Beijing viewed the US as trying to “encircle, and suppress them, and trying to deny them their rightful place in the world”, he said.

He said China sees itself as a “strong” country whose “time has come” and that it hopes to be “more assertive in national interest, including national interest overseas”, noting that Beijing would face backlash if it “pushes its way around other countries and overdoes it”.

Focus on continuity

Observers note that Wong’s foreign policy rhetoric centres on maintaining the principles of the ruling People’s Action Party since its rise to power in 1965, prioritising stability, enhancing military capabilities, and economic growth.

But sooner or later, Wong may be pushed to define what his pro-Singapore stance would look like in “practical terms”, said Chong Ja Ian, associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

“The environment for Singapore is more challenging than ever before,” he said.

“It seems somewhat strange that the approach is to do things as they have been done before because in a new geopolitical environment, you would adapt, change and update rather than to just stick with what you’re familiar with.”

“We are very careful when we conduct relationships with both [mainland] China and Taiwan, that it’s consistent with our One China policy,” Wong said, noting that if all parties in the conflict understand the risks and the red lines, that if any change happens, it is done in a way that is “peaceful and non-forcible”.

Analysts say Singapore’s unwavering stance is a way of insulating itself from internal and external pressures.

Asean question

“For Singapore, that is very dependent on established rules in its policy interactions with greater powers … what it intends to put on the line to ensure that these disputes are handled in non-coercive ways is not really known,” he said.

But analyst Low argues that Singapore is aware that it has “limited influence” over Asean.

“Every country has the right to pursue its policies according to its own interests, even those countries that lean more towards China,” he said.

“The idea that Asean should have a common position … goes against the grain of how Asean has developed historically.”

Low expects Singapore to continue its long-standing “non-aligned” policy, saying that while a great-power conflict may impact how Singapore operates, countries still have a “great deal of agency and don’t have to choose sides”.

Singapore might find itself in a tricky position if Southeast Asia becomes an arena for competition among major powers, Chong says, particularly if Asean fails to present a unified front.

“Where [Singapore] might stand in a region that is less coordinated and less effective in being able to collectively bargain or push back against major powers remains a question.

“Singapore will need to be prepared for dealing with a lot more pressure, whether this is political or in terms of economic coercion,” he said.

“These are the things that Singapore needs to show it is prepared for psychologically, but I’ve not seen much movement in that direction as yet.”